You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

Suitably restored after a brief rest, we're back at the Palazzo della Pilotta, so called because during the Bourbon period in the 18th century the Spanish troops passed the time by playing pelota in one of the courtyards. The original buildings were built in about 1583-1611, begun by the 2nd Duke, Ottavio Farnese, and were at one time connected with the Palazzo Ducale on the far side of the river.

Allied bombers, in May 1944, mistook the palace for the rail yards a kilometre or so to the north, and blew the daylights out of it. Amazing restoration works were carried out in 1947 and '48, but the mess over on the left side was retained as a memorial.

That's all new stuff, replacing the destroyed church of St Peter. Originally, the present palace complex here was intended by Ranuccio I, the 4th Duke, to function as service facilities (stables, barracks, etc.) for the Ducal Palace, which was connected by a covered 'corridor' across the river and through the Ducal Park.

Presently, the Palazzo della Pilotta houses the Galleria Nazionale di Parma, the pinacoteca or art museum; the national archaeological museum; an Academy of Fine Arts; a museum dedicated to the typographer Bodoni; the Biblioteca Palatina or Palatina Library, with more than 700,000 printed works, 6,600 MSS, and 3,000 incunabula, or books printed before 1500; and the Teatro Farnese, now the stunning entrance hall to the pinacoteca.

We're headed for the pinacoteca. As in its ducal sister city of Piacenza, when the Bourbons succeeded the Farnese in Parma, in 1734 they promptly shipped much of the dynasty's existing art collections (and home furnishings) off to their home-base in Naples, but some of it was got back subsequently and new acquisitions, including aristocratic collections, have been made since. During the French occupation of the early 19th century, a lot of it was hauled off to Paris, too, but after Napoleon's abdication the Duchess of Parma, Napoleon's wife Marie Louise, hauled it all back again in 1816.

The entrance to the National Gallery (get ready for this)

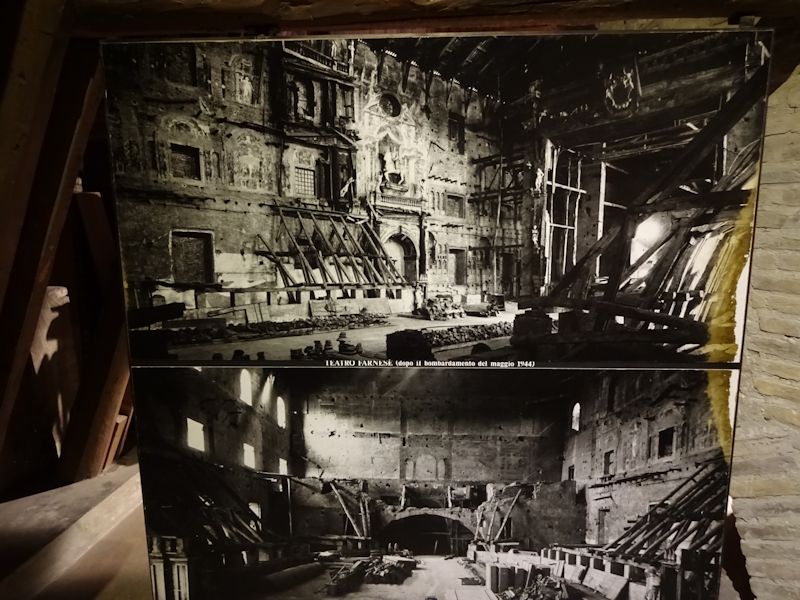

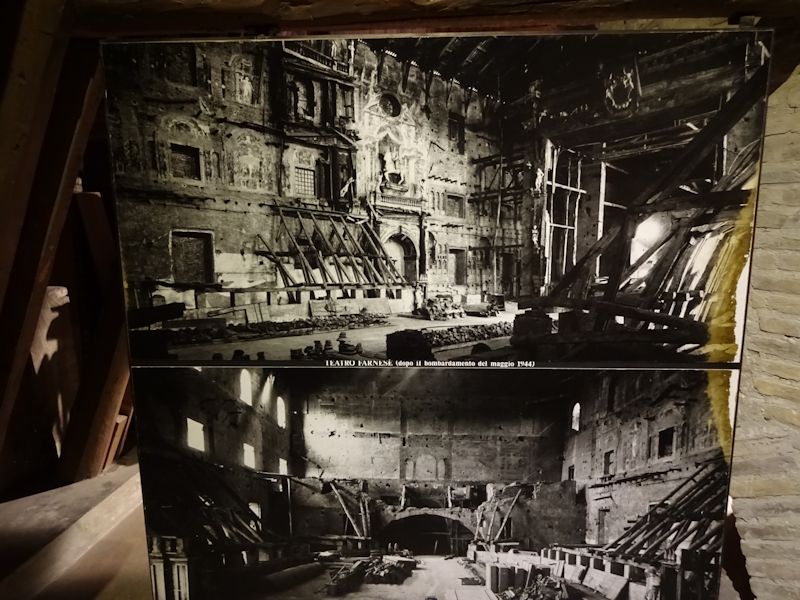

The Farnese Theatre was built in 1618 by Duke Ranuccio I, intended as an armory but hastily converted into this theatre for a proposed visit by Cosimo II de'Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, which never took place; it was inaugurated instead in 1628 for the marriage of the next Duke of Parma, Odoardo I, with another Medici, Cosimo's daughter Margherita. It was used by the Farneses for court spectacles and entertainments, infrequently, but fell into dilapidation after the end of the dynasty here, in 1732, and it took a devastating direct hit from the Allies in 1944.

The theatre is usually considered to be the first surviving theatre with a permanent proscenium arch, "fourth wall" style of theatre architecture.

The renovations begun in 1950, based on original plans and using existing materials wherever possible, were completed in 1962 and are just stunning.

For the marriage spectacle for Odoardo and Margherita in 1628, the centre was flooded for a mock naval battle, or naumachia, with pumps hidden under the stage.

There's a mini-museum under the seating, with photographs of the state of play in late May 1944.

The gallery may be strongest in medieval, frequently local and regional, stuff, and we've singled out some our fun favorites. First, as we walk in, we meet something for our collection of Madonna and Baby Nursing pictures with anatomically improbable arrangements, this by the Maestro di San Davino from Pisa/Lucca, early 15th century. The lady second from the left is the archangel St Michael.

This Assumption of the Virgin with an entourage of (apparently) nasty little red demons is here attributed to Botticelli or his circle (ambito). The cord hanging down from her waist looks like her famous girdle, the Sacro Cingolo, which she presented to Doubting Thomas, now in the Duomo di Prato.

The Madonna and Child Enthroned, with one of the stranger God the Fathers anywhere . . .

He certainly looks paternal, and beatific, and relaxed (by Jacopo Loschi, 1471)

These are three of the four very neat detached frescoes of "Works of Mercy" by an anonymous Parmigiani from the mid-15th century, taken from a medieval hospital in town.

Only three here because the fourth one didn't come out well -- we're in senza flash mode here, and rightly so.

It looks like someone in the right background, Christ? the local bishop?, blesses these 'opere di misericordia'.

This is a Madonna and Child (ca. 1500) by Cima da Conegliano; the lady on the left is St Michael, the gent on the right is St Andrew.

Leonardo's stunning head of a young lady, known as La Scapigliata, oil on wood from about 1500-1510

The Pallavicini were one of the leading clans of Parma and the region (and in later centuries one of the families that carved up the Parmigian contado or countryside into nearly independent fiefdoms), but we're interested in them chiefly because a cadet member of the family, Sir Horatio Pallavicino, of the Genovese banking branch, converted to Protestantism and moved to England, where he became Queen Elizabeth I's chief financial agent, a shipping magnate, occasional spy, and in effect the English ambassador to Protestant states in Germany.

This, however, is a family portrait of Rolando Pallavicino (d. 1529) and his wife, with his sullen daughter Barbara, whose marriage off to Count Ludovico Rangoni in 1525, without Pope Clement VII's permission, resulted in a big diplomatic mess. One of two big messes, actually: Rolando had his brother Polidoro jailed for being of unsound mind in order to get the family inheritance, and subsequently Ludovico and his brother Guido Rangoni sued Polidoro's heiress Livia and her husband, the diplomat Sir Gregorio di Casale, to gain control of the inheritance, an unsuccessful legal battle that was finally settled in 1695 [Catherine Fletcher, Our man in Rome: Henry VIII and his Italian ambassador, 2012, pp 84-86]. The picture is by Francesco da Cotignola, called Zaganelli, ca. 1515.

It's like a breath of fresh air, or something. Having seen hundreds of paintings of St Sebastian riddled with hundreds of arrows all over him, it's refreshing to see a nice economical, clean head shot. Especially as it doesn't seem to have upset him very much. This is signed by Jehoshaphat Araldi, early 16th century.

The lady with the huge sword is the archangel St Michael whaling on a webfooted demon, for reasons unexplained, whilst folks are amusing themselves round a table or gambling perhaps, and the Virgin Mary is ascending into Heaven with lots of angels, which didn't make it into this photo. By Dosso Dossi, the court painter of Ferrara, and his brother Battista, ca. 1533.

Moving on to the Renaissance-and-after rooms, Kristin's admiring four by Sebastiano Ricci.

Along a balcony above the medieval gallery

This is a fascinating exhibition of pictures of Parma in the 19th century

A perhaps-unflattering portrait of a young lady with a puppy, by Pierfrancesco Cittadini, a noted mid-17th century portraitist and pupil of Guido Reni

We collect Biblical beheadings and, especially, Judith and Holofernes; the front-runner so far is definitely Artemisia Gentileschi's, but this one, here attributed to the 17th century Frenchman Teofilo Trufamonti, is a competitor. Oddly, he's best known for a Judith and Holofernes, but it's not this one.

This is meant to be Duke Ranuccio I Farnese, a pleasant looking chap credited with Parma's "cultural renewal" and urban improvements during his tenure, 1592-1622. But he's best known for the "Great Justice" or Sanvitale Conspiracy, in which he uncovered an assassination plot by discontented local aristocrats and had a large number of them beheaded in May 1612 in what's now the Piazza Garibaldi, including the Countess Barbara Sanseverino, and kept all their properties. When he publicized manifestly untrue charges, wrought under torture from G. Sanvitale, Count of Fontanellato, of complicity in the plot by big-name lords like the Gonzaga Duke of Mantova and Este Duke of Modena, he was everywhere ostracized by polite society. This is attributed to the Bolognese Agostino Carracci, brother of Annibale, late 16th century.

This is Isabella Clara Eugenia, wee little daughter of Philip II of Spain, in about 1626, attributed to the workshop of Van Dyck; she essentially ruled the Spanish Netherlands from 1601 with her husband the Archduke Albert, but retired to a Franciscan convent in the mid-1620s and died in 1633.

Here's the wee lass in about 1573, painted by Sofonisba Anguissola, now in the Sabauda Gallery in Turin. |

We're being shuffled out now, closing time for many parts of the gallery, and in fact the Baroque gallery (up that stairway) never opened at all. "Understaffed", we're told, but we've been instructed to show up at the Leonardo 'Scapigliata' tomorrow at 10 a.m. to be let in to see the Baroque stuff for exactly one half hour.

Bacchus with a fawn, from the Farnese Gardens on the Palatine in Rome. The gardens were created in 1550 by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, older brother of Ottavio the 2nd Duke of Parma and Piacenza.

Only the Correggio/Parmigianino wing is still open and here we are. This is a sinopie or cartoon on cloth for the figure of the Virgin Mary in Correggio's Assumption fresco in the Parma cathedral cupola.

Correggio's Lamentation, ca. 1524. We were rushing through here at this point, and will be back tomorrow, at first light, more or less.

This is a picture celebrating the 'tribal spirit'.

We're dashing over to check the opening hours, for a subsequent rewarding visit.

The rail station, built in 1859 and recently renovated . . .

. . . with a bus station underneath.

All aboard. A local, evidently, but the high-speed trains on the Milan-Bologna lines come through here.

This is (I think) the Str. XX Settembre, just south of the rail station . . .

The classic scowl of fury by the beloved Padre Pio (1887-1968), the sainted stigmatist

A Latin cross plan with a nave and two aisles, and with a dome at the crossing.

The abbey church of San Giovanni. Now it's time to get focused on dinner.

Dwight Peck's personal website

Dwight Peck's personal website