You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. {1}

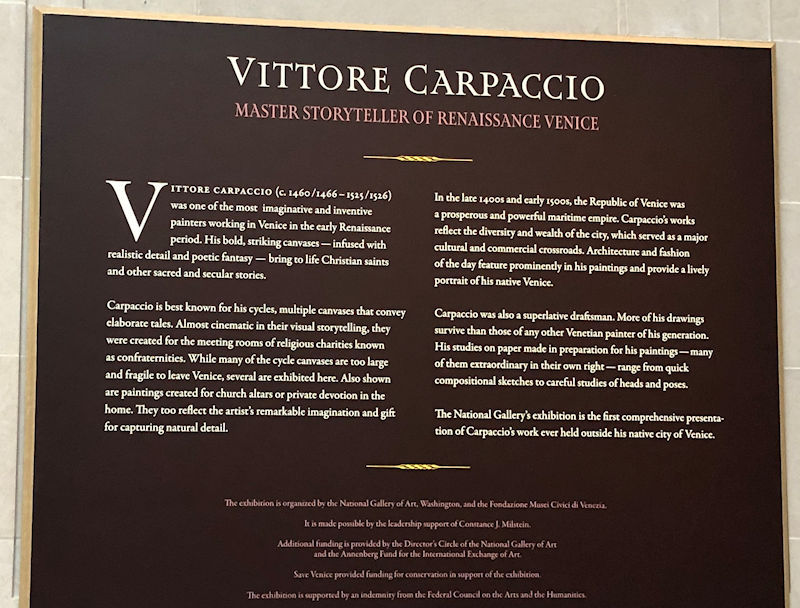

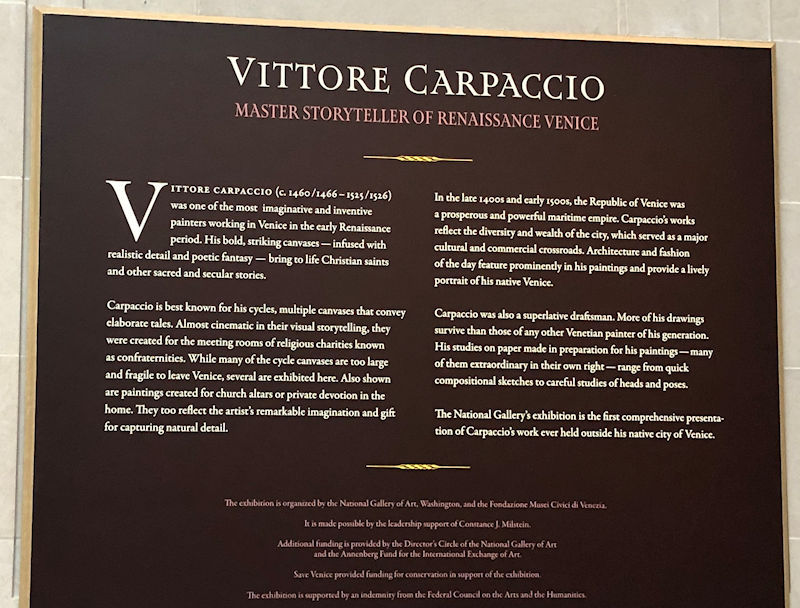

The Vittore Carpaccio exhibition and assorted Renaissance-Era other stuff

Kristin's just returned from Chicago and we've met up in an hotel near the Dulles airport, and now we're taking advantage of proximity to meet up with Alison for a visit, first to the National Gallery of Art, and then (after a poke lunch) to the National Museum of the American Indian. 5 January 2023.

That's the Washington Monument, by the looks of it. One's first and only visit to D.C. was in 1977, for a festive do at the Library of Congress, but he saw little of the city then and remembers less.

The US Capitol building and a garbage truck. This city is filled with hidden ironies.

The 'Smithsonian Castle', the Smithsonian Institution's HQ, facing onto the National Mall; as of February 2023 (i.e., now), it's begun a five-year renovation.

We're lost.

Luckily, cellphones prevail, and Alison is waiting for us at the National Gallery, supplying us with helpful suggestions.

In the excitement of the moment, one of our party neglected to take a photo of the National Gallery of Art now that we're here, so subsequently we've nicked this fine photograph from the Wikipedia Creative Commons (photo by Alvesgaspar, 2016).

Gracefully welcoming security arrangements, and admission is free.

Up one floor to the emphatic Rotunda, as we're looking for . . .

. . . the exhibition of the Renaissance Venetian artist Vittore Carpaccio, a minor favorite of ours.

According to the welcoming panel, this is the first major exhibition of Carpaccio's pictures outside of Venice.

Here's an example of why he comes so well recommended -- this is a Virgin and Christ Child with two saints, probably Cecilia on the left, and, given the arrow she's holding, perhaps St Ursula on the right. It's dated to ca. 1492/1495.

Carpaccio had recently done a large-scale series on the 10th century legend of the British Christian princess Ursula who showed up in Cologne with her entourage of 11,000 virgins to be married but were all massacred, supposedly in ca.385, either by Germans or by Huns; the others were beheaded but Ursula was shot with an arrow by the Hun chief; the figure of 11,000 may come from a typo in some MS version; the cult took off with the founding in 1535 of the educational Order of Ursuline nuns. The standard story appears in the 13th century Golden Legend (Penguin edition, pp. 279-82).

'A Meditation on the Passion' shows Christ midway between death and 'reawakening', sitting on a throne backed by a fake Hebrew text. St Jerome's on the left and the prophet Job on the right, with his cute slippers on. Dated to 1494-1496.

Carpaccio long held a special affection for the legends of St George and his dragon, of which several versions remain. Dated ca. late 1490s.

Carpaccio (a variant of the family surname Scarpaza) was born in ca.1460-1465 near Venice and seems to have studied in the workshop of Giovanni & Gentile Bellini. He worked at altarpieces & large cycles and is said to be best known for his large urban scenes, especially those showing attributes of Venice to good advantage. His best known works were done between 1490 & 1519, though by the 1520s he was considered to be becoming old-fashioned -- he was in a second rank of acclaim in his time, but nevertheless was appreciated by Vasari as among the best Venetian artists. His most important work, a narrative cycle done with Giovanni Bellini, was lost in a fire in the Doge's Palace of 1577. Late in life, he was succeeded by his two sons and retired to Capo d'Istria (Koper), now in Slovenia, where he died in 1525/6.

This is St Augustine in his Study, a notably Renaissance study with books and artifacts, and an astrolabe, strewn all over. It illustrates the story that he was writing a letter to St Jerome and was miraculously notified by a shaft of bright light that Jerome had just died. Dated ca.1502, like most of his paintings done on canvas rather than panel.

This one is about an unfamiliar classical tale of the Departure of Ceyx from Alcyone (King Ceyx was shipwrecked and Alcyone committed suicide). The picture is most interesting for the thoroughly contemporary Venetian setting and clothing. Dated 1498-1503.

The Birth of the Virgin, Mary's elderly mother Anne staying in bed and her aged father with his cane. The Baby Jesus, getting a wash-up by his nurse, has got a halo on, even at his tender age. Dates 1502/3.

The next in this Virgin Mary series is the Presentation of the Virgin in the temple in a mostly Venetian looking Jersusalem, but also including palm trees and minarets.

Here Mary is being betrothed to Joseph -- the panel points out that all her suitors have brought sticks to the ceremony, but when only his burst into flowers they all broke there sticks in frustration. The menorah is a nice touch.

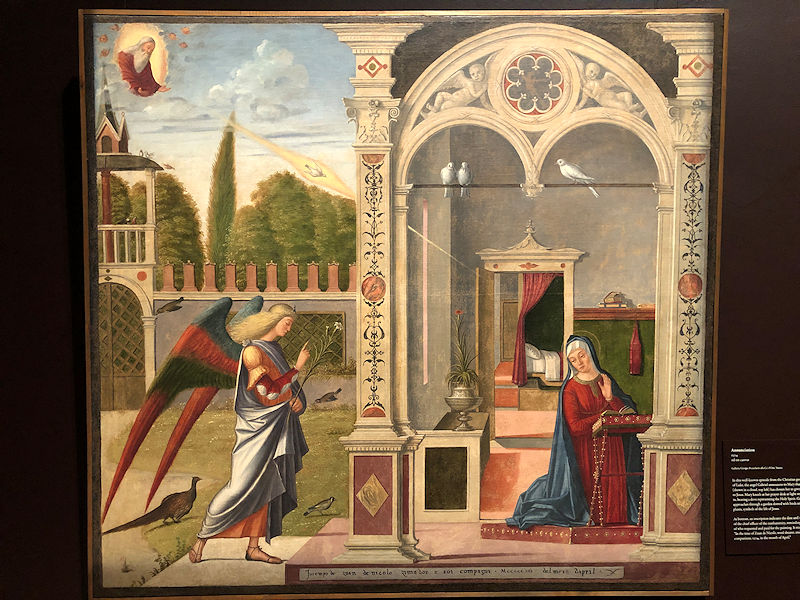

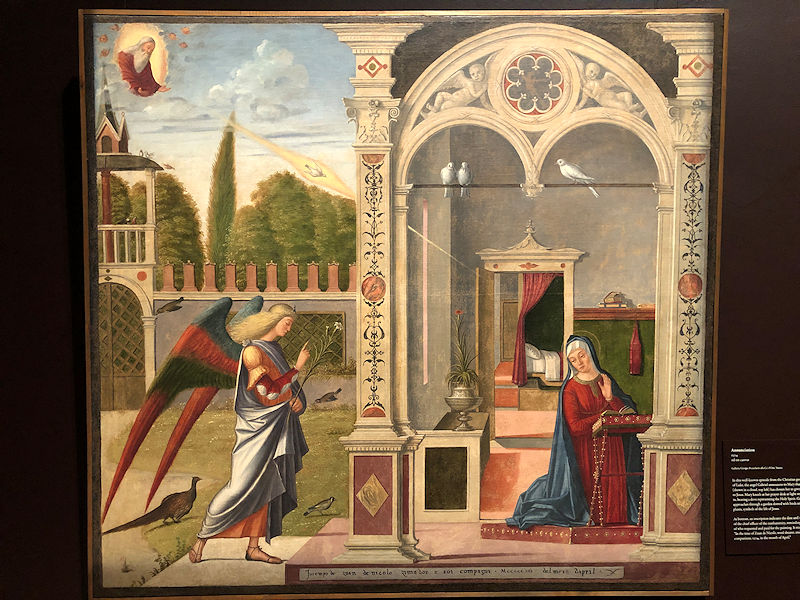

Next in the series, the Annunciation (1504). The angel Gabriel in explaining to Mary why God is shooting down at her a Holy Spirit/dove in a laser beam. Across the bottom is a text identifying the head of the citizen confraternity, a wool shearer, who with his companions had commissioned the work in April 1504.

This one, called the Visitation, shows a pregnant Mary embraced by Elizabeth, pregnant with John the Baptist, with the aged husbands Joseph and Zacharias just hanging out. Dated 1504/8. As usual with Carpaccio, the perspectives are well done, and apparently some have suggested that he had been exposed to techniques from the Netherlands.

The Dormition -- the Virgin, in this tradition, didn't die, she just went to sleep and would soon wake up in Heaven. Jesus is sitting up in Heaven conversing with a tiny young girl, who is actually Mary's soul going home. The three guys in black, with traditional funeral candles, are thought to be the Albanians who'd commissioned the painting.

This one is called the Virgin Reading, but she's wearing high-class Venetian fashions instead of the traditional blue cloak, and she's shown in profile, so maybe she's some other saint, or neighbor lady. But the explanatory panel argues that the little bit of a baby on the left probably confirms that she's a Mary in Carpaccio's unconventional version. (We get to choose.) Dates ca.1510.

St George is back, and so's the dragon. This is an altarpiece still in the church of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, dated 1516. Across the bottom are four images of a predella, hanging down in front of the altar, showing gruesome scenes from George's tortures before being martyred, but our camera didn't realize that.

This shows the Ordination of St Stephen (1511), the first in a narrative cycle that Carpaccio made on Stephen's life for the Scuola di Santo Stefano. Here, following Acts of the Apostles, Peter ordains Stephen in front of the Jerusalem temple soon after the Crucifixion. The background is an astonishing architectural gallimaufry.

This is early in Stephen's brief career, so here, thankfully, he's not shown with the three silly stones of his martyrdom, one of them balanced on his head.

This silly-looking winkie, known as the Young Knight in a Landscape (1510) [we saw it in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid in 2012, but 'No Photos'], is either pulling out or putting away his sword. It's not known whether he was a real live guy or a commemoration of a newly dead one, but 'either way, the knight is a personification of chivalry', given some of the symbolic attributes.

Virgin and Child (ca.1502/5), from the National Gallery's own collection, is especially prized for reflecting 'Carpaccio's delight in depicting nature'.

Here are my three favorite (male) saints -- on the left, St Peter Martyr (St Peter of Verona), the energetic Dominican heretic hunter, very famous, who in 1252 was assassinated by two hitmen hired by Milanese Cathar heretics. He became a saint in 1253, the 'fastest canonization in papal history'. Then we have St Sebastian with his arrows, and St Rocco or Roch, the patron saint of the plague, showing off his buboes; these two are frequently found together, in art, that is.

Here's God, obviously. As usual, with that overstated patriarchal white beard. He's holding the 'orb of rulership' (of the whole world, that is), and giving his blessing. Dated ca.1518-20.

And here's Jesus, training to get that orb-and-blessing routine down right. Jesus never graduated with that big white beard, as far as we know, so the little ginger one will have to do. Dated 1503/8, it's called Salvator Mundi, savior of the world. (Any day now.)

One of our favorities in the exhibition -- this is the Doge Leonardo Loredan, who served from 1501 to 1521 and insisted on posing in this 'magnificant official costume'. (Not the head of state 'you'd like to have a beer with'.) The panel notes that the view out the window shows what he would have seen from the Palazzo Ducale in Venice [looks like the abbey of San Giorgio Maggiore].

This strange thing is meant to show a mystical vision experienced by the prior of a monastery in Venice, in which he sees a solemn procession of martyrs carrying crosses; the idea is that their intervention prevented the plague from infecting the monastery. The picture's also prized because it records the interior of a church long since demolished.

This picture in the altarpiece is understood to be this next one, called . . .

. . . The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand Christians on Mount Ararat (1515). This huge altarpiece decoration had been placed on a family's altar in the church of Sant'Antonio di Castello in Venice.

The legend from the lives of saints collections speaks of a mass crucifixion of recent Christian converts in which the unspeakable perpetrators are shown as a mix of ancient Roman officers and contemporary Muslim Rulers, representing the Holy Roman Empire and the Ottoman Empire, both of which were threatening the territories of the Venetian Republic at the time.

It's got pretty amazing detail, and a great lot of it.

To make life easier for future art lovers, Carpaccio has thoughtfully signed and dated the picture in the lower left.

This records the story of the Flight into Egypt (ca.1516/18), from an improbable hint in the gospel of Matthew, 2:13-15: 'behold, the angel of the Lord appeareth to Joseph in a dream, saying, Arise, and take the young child and his mother, and flee into Egypt, and be thou there until I bring thee word: for Herod will seek the young child to destroy him. [14] When he arose, he took the young child and his mother by night, and departed into Egypt [15] And was there until the death of Herod: that it might be fulfilled which was spoken of the Lord by the prophet, saying, Out of Egypt have I called my son.' Matthew has left it a bit unclear whether the old fellow was really fleeing from Herod or just trying to live out some ancient prophecy.

The theme of the Pietà, the panel says, was a northern European subject that Carpaccio helped to popularize in Italy. This is dated to ca.1515. The ginger hair is probably the artist's original contribution.

A matching set of two of the four allegorical figures representing, here, Temperance (mixing water into a bowl of wine) and Prudence (checking in a mirror that 'she is careful in all her actions'). Ummm. The other two of the four cardinal virtues are Justice and Fortitude, according to virtue experts ranging from Plato and Aristotle, the Stoics, and the Christian authors like Ambrose, Augustine, and Thomas Aquinas. Dated 1514/16.

Carpaccio fans will undoubtedly be thrilled to find these pictures in the exhibition here, which runs from Nov. 20, 2022 to Feb. 12, 2023 (which also means that, as of this writing, it's already moved on to the Ducale Palazzo in Venice for March through June 2023). But the Gallery has a web presence about it here.

In a short visit, we have no time for the Impressionists, Expressionists, and Contemporaries -- first things first: we were starting with the medievals and then the Renaissancers, but we found that the medieval wing was closed for renovations, so here is Tinteretto's Worship of the Golden Calf (ca.1560; we've jumbled up the chronological order somehow).

And Tinteretto's Susanna (ca.1575), which some of us might find pretty uninteresting, but . . .

. . . how could Arcimboldo's crazy pictures ever be uninteresting? This is called 'Four Seasons in One Head'! All of his stuff that we've seen follow the same method but are all different. There's even a pizza restaurant on the main street in Sirmione [right], on Lago di Garda, named L'Arcimboldo. And one in Bologna and another in Verona; maybe more.

. . . how could Arcimboldo's crazy pictures ever be uninteresting? This is called 'Four Seasons in One Head'! All of his stuff that we've seen follow the same method but are all different. There's even a pizza restaurant on the main street in Sirmione [right], on Lago di Garda, named L'Arcimboldo. And one in Bologna and another in Verona; maybe more.

Giovanni Arcimboldo (ca.1526-1593) was brought up in Milan and painted frescoes in churches in the area, but migrated to Vienna in 1562 as court portraitist to the emperor, and then to Prague with the emperor's two successors. He continued to do normal religious & portrait paintings, which are said to be unremarkable, but he is revered for his vegetable freak-shows, which are now understood to be deeply satirical (he did one portrait of the HRE Rudolf II as Vertumnus, god of the seasons). His works are all over Europe, even the US, because the Swedish army looted a mass of them when they sacked Prague in 1648. He was not well known historically until Salavador Dali & his friends discovered him. We've seen & when permitted photographed his things in the Louvre, the Uffizi, in Cremona, Brescia, and (I think) the Prado.

Aw, how cute! That's the Infant Bacchus (with a cute little jug of wine), by Giovanni Bellini, ca.1505/10.

-- Oh, hello!

This is by one of our favorites (after an exhibition in the Palazzo Venezia in Rome in 2008 ['No Photo!']), Sebastiano del Piombo, called Portrait of a Young Woman as a Wise Virgin (ca.1510).

Circe and Her Lovers in a Landscape (ca. 1525), by Dosso Dossi of the 'School of Ferrara'. Circe was a famous enchantress, a daughter of a Titan or the sun god Helios, who was famous for turning enemies and boyfriends into animals; she turned Odysseus' whole crew into swine and would only make them human again if he lived with her for a year, so he did. In which time, they had two sons; go figure.

A 'Portrait of a Man' [obviously], also at least attributed to Dosso Dossi, ca.1527-30. The little flower thing must symbolize something.

Here's Jacopo Tintoretto again, with the Doge Alvise Mocenigo and Family before the Madonna and Child (ca.1575). A pleasant enough looking family, but the Madonna and Baby Jesus must have had more on their agenda today.

Venus with a Mirror, by another Venetian, Tiziano Vecelli aka Titian (ca.1575)

And another Titian, Woman Holding an Apple (ca.1550)

This fellow should need no introduction, but may. He's Pietro Bembo (1470-1547), born in Venice, a super-great humanist, brilliant scholar, poet, and free thinker, who did more than anyone to elevate the Tuscan dialect of Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch into the national literary language. He was patronized by the Este court in Ferrara, and during his second sojourn there, in 1502-3, he apparently really did have a love affair with Lucrezia Borgia, the Duchess there; they exchanged love letters until she died in 1519. He was patronized by all the best courts, and appears as one of the cultured participants in the dialogues set in Urbino in Castligione's Book of the Courtier (pub. 1528). In his age, Pope Paul III made him a cardinal in 1538, for which he had to follow up by becoming a priest; that could be the occasion for his hiring Titian to make this picture of him, dated to 1539/40.

Alison and Kristin, intent on art. One recalls trying to see any art on display in the Vatican Museum, and grins.

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (ca.1545), by Jacopo Bassano, originally Jacopo dal Ponte born in Bassano del Grappa, and succeeded by his four sons there, all of whom were very popular in Venice. We pilgrimaged to Bassano del Grappa in 2017, mainly to look into the WW2 Resistance situation there, including Hemingway's time there, but also to look up the whole Bassano family.

A Concert (ca.1518/20), by Giovanni Cariani (ca.1485-1547), unknown to us. According to Wikipedia, he came from Bergamo but trained with either Giovanni Bellini or Giorgione in Venice and died there in 1547.

An interesting Portrait of a Lady in White (ca.1540), by Il Moretto da Brescia (Alessandro Bonvicino), who's also semi-unknown to us though he made one of the two classic harsh portraits of the forbidding Dominican Girolamo Savonarola posthumously in 1524, which we saw in Verona, and a Mary Magdalene that we came upon in the Art Institute in Chicago.

A Young Woman and Her Little Boy (ca.1541) -- though the little boy actually looks sort of dead -- by the Florentine Agnolo Bronzino.

That's the famous tondo by Raphael, ca.1510, called The Alba Madonna.

Lorenzo de' Medici, 'the Magnificent', a painted terracotta made in Florence, according to the label, probably from a model by Verrocchio.

And here's Lorenzo's younger brother Giuliano, in his scariest armor, by Verrocchio in about 1478, probably meant to commemorate his recent death.

This is Botticelli's portrait of Giuliano de' Medici, one of several versions, the original of which was probably also made soon after his death. Lorenzo and Giuliano were attacked in the Duomo of Florence in April 1578 by a rival faction in the city, in what is known as the Pazzi Conspiracy. Lorenzo escaped, but Giuliano, then only 24 years old, was stabbed 19 times and died. He was unmarried but his illegitimate son, Giulio de' Medici, born a month after Giuliano's death, eventually became Clement VII, who was the Pope at the time of the awful Sack of Rome in 1527.

Botticelli's Adoration of the Magi (ca.1480)

Filippino Lippi's Adoration of the Child (ca.1475/80), by an angel with translucent wings.

Madonna and Child, by Sandro Botticelli, ca.1470

Another Madonna and Child for comparison, by Domenico Ghirlandaio, ca.1470/75 (arguably more interesting?)

A crowded Crucifixion scene, by Luca Signorelli, ca.1504/5

Pietà, or Dead Christ Mourned by Nicodemus and Two Angels (ca.1590), by Filippino Lippi

-- Where to next?

As mentioned above, the medieval section is closed off for renovations, but we've just learnt that a lot of the good stuff has been moved elsewhere in the building, so we're going to continue moving backwards through time, and then just wander about for a bit before a late lunch.

Next up: Some more of the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Dwight Peck's personal website

Dwight Peck's personal website

. . . how could Arcimboldo's crazy pictures ever be uninteresting? This is called 'Four Seasons in One Head'! All of his stuff that we've seen follow the same method but are all different. There's even a pizza restaurant on the main street in Sirmione [right], on Lago di Garda, named L'Arcimboldo. And one in Bologna and another in Verona; maybe more.

. . . how could Arcimboldo's crazy pictures ever be uninteresting? This is called 'Four Seasons in One Head'! All of his stuff that we've seen follow the same method but are all different. There's even a pizza restaurant on the main street in Sirmione [right], on Lago di Garda, named L'Arcimboldo. And one in Bologna and another in Verona; maybe more.