You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

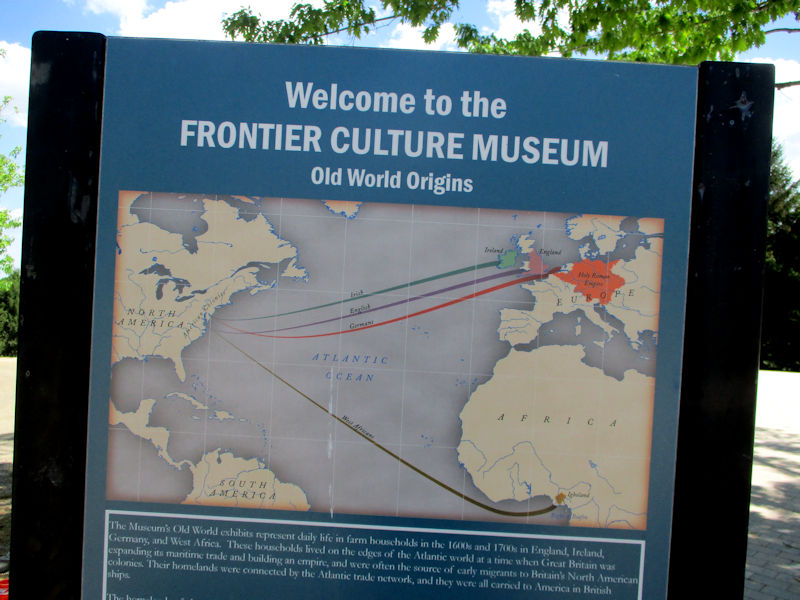

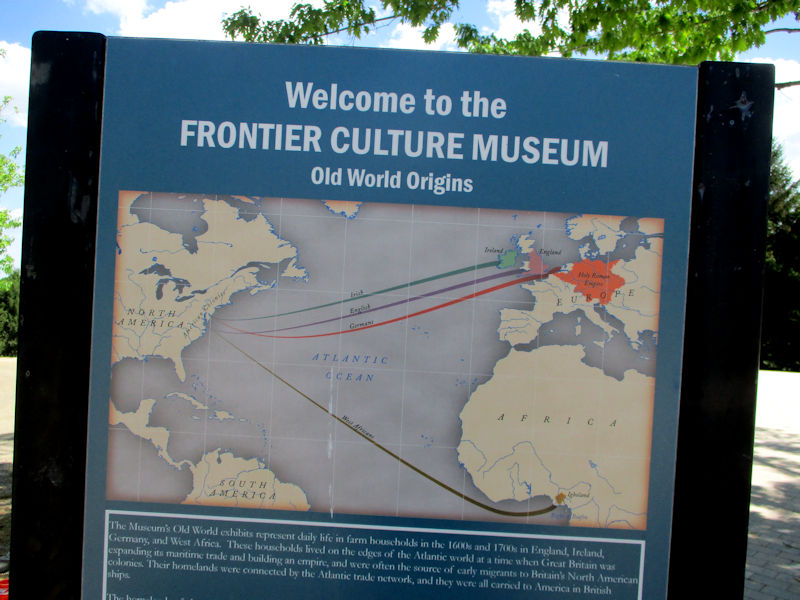

The Frontier Culture Museum, Staunton, VA

Interesting echos from the post-medieval past, 3 May 2019

Folks in Oklahoma or South Dakota might be surprised by the definition of 'frontier' here, but given the circumstances, it suits. In the mid-18th century, the mountains of western Virginia marked the limits of most colonial settlement. Augusta County, now in the Shenandoah Valley with its county seat in Staunton, was organized in 1738 and theoretically extended to the Pacific Ocean.

As immigrant settlers were moving westward in the latter part of the century, impelled by coastal population pressures and displacing the Native American residents mostly forcibly, early rearrangements of jurisdictions in West Virginia, Ohio, Illinois and elsewhere cut Augusta County back to its present dimensions by 1790.

Aw shucks!! We'll have to leave 'em in the car. Staunton itself was first settled in 1732 and was part of the formal grant by the English crown authorities creating Augusta County in 1736. From 1738 to 1771 it served as the regional capital of the "Northwest Territory", with the westernmost courthouse in Britain's American colonies before the Revolution. It was at the time a major staging area for settlers moving farther west into the Appalachian mountains, and the Frontier Culture Museum, a property of the Commonwealth of Virginia, is intended to recreate some of what life might have been like in those years.

The Museum's 10 or so historic buildings are intended to demonstrate what life might have been like in the 17th to 19th century in the countries from which Shenandoah settlers tended to have immigrated and for the settlers themselves in the Valley in the 18th and 19th centuries. They are laid out with appropriate landscaping and mostly volunteer staff offering explanations and demonstrating period crafts and household tasks. It's a kind of mini-Ballenberg.

[The astonishing Ballenberg Open-Air Museum (Frielichtmuseum der Schweiz), overlooking the Lake of Brienz in Switzerland, opened in 1978 and presently has over 100 historic town and farm houses and outbuildings that have been dismantled, transported, and rebuilt using original methods in areas of the park corresponding to their original locations around the country. There, too, staff demonstrate common household tasks and crafts, as well as original building techniques, like thatching roofs, on new acquisitions.]

Most of the western Virginia settlers seem to have originated in Germany, England, and Ireland, along with some 250,000 slaves imported to the region from West Africa -- accordingly, the exhibits feature mostly original, reconstructed buildings acquired and transported in pieces from those places.

Our first stop is a German farm from the 18th century, evidently moved here from the Rhineland, where Protestant farmers from Württemberg and the Palatinate were recruited by the English government and private developers and investors.

This is the main farmhouse, divided into three rooms in effect, which is said to have been an innovation from the early 18th century, before which time we're to believe that the peasant farmers lived in one-room hovels.

We're entering through the back door, it seems . . .

. . . into a workroom, followed by . . .

. . . the kitchen in the centre of the house. The method of cooking, we were told by the helpful docent, is characteristic of the farms of the original area, a small tabletop fire under a pot or pan on a trivet, with no need for a large and wasteful fireplace.

Another look at the kitchen -- the third room in the house, at the far end, was called the Stube and was a heated and furnished room that served as a living- and diningroom, a common space for the family. (Sleeping space appears to have been upstairs under the roof, but we didn't notice.)

Livestock on the German farm

The German farmhouse and its 'front door' leading to the hall and kitchen

In the German barn

A bit farther along the road, this is an Irish farm and outbuilding also from the 18th century. Ireland was largely Catholic, of course, and life for the Protestant descendants of the Tudor 'Ulster Plantation' and Presbyterian dissenters of Scottish descent could often have been fairly awkward. Many tenant farmers and families answered the ads by government and colonial proprietors to emigrate to the Pennsylvania colony, whence in time they moved on down into the 'Great Valley' of the Shenandoah.

These buildings came from the County of Tyrone in Ulster Province in the north of Ireland, and their occupants, had they fetched up here, would in time have been known as the 'Scotch-Irish' to distinguish them from the Catholic Irish who came in numbers to the US in the mid-19th century.

A rudimentary livingroom and hearth . . .

. . . with a short person's bed.

Another view of the livingroom by the fireplace

In a second room, working facilities -- many of the Ulster farming families were involved in growing flax and weaving linen for the markets in addition to their subsistence farming.

These buildings came directly from Ireland -- the information panel points out that these immigrants to western Virginia and onward into the Appalachian mountains maintained the same two-room style but necessarily used logs instead of stone in the construction, as here.

A cute little creek running through the backyard

And three geese, one of them emphatically a minor

The Irish farm buildings from the backyard

This, nearby, is the Irish forge, also an 18th century original, this one from County Fermanagh in Ulster. Skilled craftsmen were in short supply at the time, and colonial administrators recruited blacksmiths and craftsmen assiduously for the journey to the colonies.

This gentleman was happy to demonstrate his art for us whilst also performing all of the ironwork tasks required for the Museum's facilities (and giftshop). (In keeping with the theme of authenticity, he is not wearing protective eyewear.)

The Irish forge from a small pond behind it

A new friend

This is said to be a yeoman farmer's household from the West Midlands of England in the 17th century. According to the info panel, the landholding farmers, called 'yeomen', who immigrated to the colonies chiefly from the region between London and Bristol, employed the use of tenant farmers and agricultural laborers, many of whom had been displaced in England by the 'enclosure' of the common lands of the medieval villages.

The English houses seem typically to have been more comfortable than the German and Irish ones we've seen, with more rooms and better furnishings.

Like that thing, and there is a central staircase to sleeping quarters on the first floor (which however are off-limits to visitors, because of safety regulations, we were told)

A common room, for work and play

Out the back door

The English house (very Shakespearianish)

The elaborate chimney is dated 1692, but might have been added later (we suppose).

A tiny thoughtful goat

To acknowledge the presence and contributions of the many slaves imported to Virginia, the Museum has tried to recreate an 18th century West African farm from 'Igboland' in what is now Nigeria.

And for balance, this is meant to illustrate how a native American community might have lived after having been pushed westward 'beyond the edge of colonial settlement' -- this is called 'Ganatastwi', which is said to mean 'small village' in the Onondaga Iroquois language, and is intended to commemorate 'the hospitality, generosity, and cooperation of the American Indians of the continent's eastern coastal plain and woodlands'.

This unimpressive accommodation is meant to illustrate how the settlers in the region in the 1740s probably housed themselves, and it's definitely pretty raw stuff.

By the late 1720s, we're told, German and Irish farmers from Pennsylvania were moving into the Appalachian mountain valleys in search of land near water to be cleared and established as freehold farms. Not much is said here about the previous residents on the land -- according to the information panel, "Native Americans lived in many backcountry areas before the arrival of Atlantic settlers. They established home sites and fields on the best available locations. Shrewd early settlers selected these sites, leaving poorer land for those who followed."

It seems to be understood that this one-room hovel would have been thrown up quickly, whilst land was being cleared and farming got underway, with the intention of improving the accommodations in due course.

A fairly grim existence. And with no Internet! They probably had a bible, though.

By the Revolutionary era, we're told, the Appalachian frontier had become a staging area for the westward expansion of white settlements into the Ohio Valley and, by the 1820s, beyond the Mississippi. This is a more substantial farmhouse and outbuildings from the 1820s, when towns and more modern infrastructure, like roads, had had time to evolve in the Shenandoah region.

The information panel here points out that in the census of 1820 there were 31,000 African Americans in the Valley, 25% of the total population, and most of them were enslaved -- there were few large plantations in this region, however, with large slave populations: "Only a small part of the Valley's white population owned slaves, and most of those owned only a few. Slave rental was common, and this practice distributed the use of slave labor more widely." It's not entirely clear here from whom the slaves were rented during peak times.

The back porch of the 1820s American farmhouse

Much roomier; only partially furnished so far

The 1820s Shenandoah region farmhouse from the east

And again

Just nearby, this is a representative schoolhouse from the 1840s, when educational services and facilities were usually arranged by local families or communities, if at all, and school attendance depended upon the seasonal agricultural workload for the kids.

Teens on the back row, preschoolers in the front

An 1840s glance toward the future -- a future of Waffle Houses alongside the interstate highways (in this case, I81)

And just 400 meters north of the schoolhouse, that is the disused DeJarnette Sanitarium, founded by Dr J. DeJarnette in 1932 -- "DeJarnette was a respected doctor among the white Virginia elite at the time, but his career would ultimately be defined by his strong support for eugenics, specifically the forced sterilization of the mentally ill and others he deemed 'defective'” [source]. Forced sterilization continued in Virginia into the 1970s, but in 1975 the state transformed the institution into a children's mental hospital -- that was moved to the Western State psychiatric hospital 2km to the north in 1996 and these buildings have been vacant ever since. The Lowe's and a Walmart 'Supercenter' are just 300m farther north.

Across the lane, this is another American farm from a slightly later period: 'The 1850s American Farm represents life on the old frontier during a time of great economic, social, and political change in the United States'.

The stone building in the foreground is a spring house, or water source, and the white outbuilding on the right is now used as a smokehouse for meats, etc, though apparently its original function isn't known.

The 1850s farmhouse has recently had a facelift -- photos from a few years back show a fairly ramshackle, saggy sort of structure.

Like this.

Our knowledgeable docent is rushing out to greet us.

The spring house, schoolhouse (with bus stop in front), and former hospital on the hill

An upstairs bedroom, evidently for the kids (the tiny master bedroom is on the ground floor) . . .

. . . and another first floor bedroom, with trundle bed for convenience, and . . .

. . . this, under the roof, is described as the servants', or perhaps the slaves', room.

A local resident

We are concluding our visit. The only important building not pictured here is a large, well renovated barn in the centre of everything, described as the 'lecture hall' and apparently with some sort of art studio included. There is also an 1820s Pennsylvania German 'bank barn' still under construction.

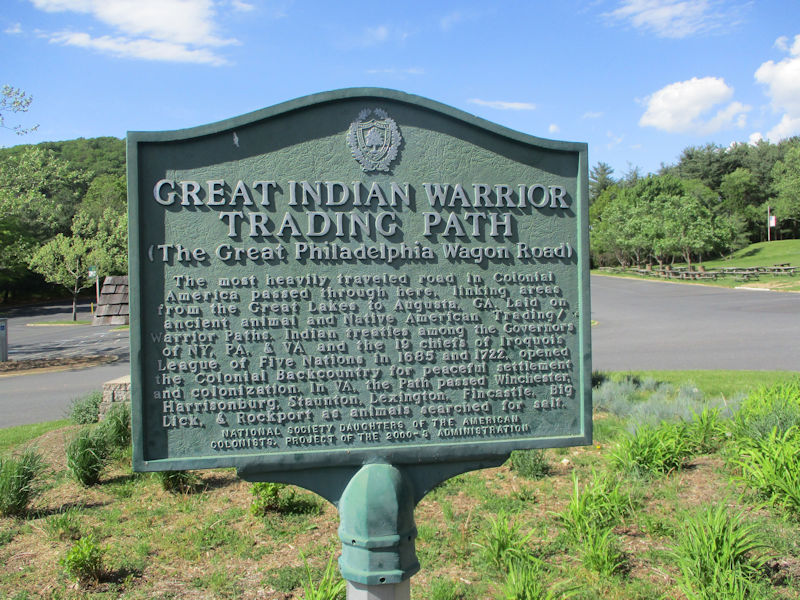

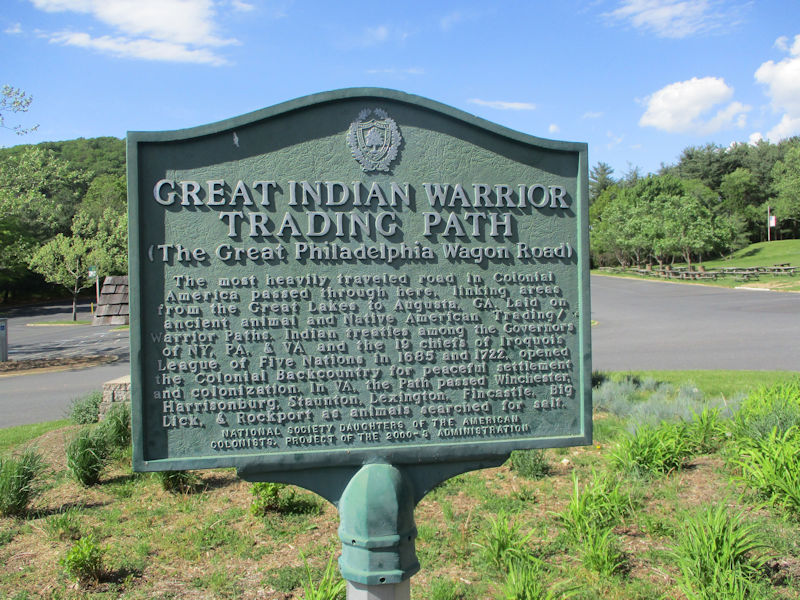

It's reassuring to learn that Native American treaties with white governors 'opened the colonial backcountry for peaceful settlement and colonization'.

Next up: Lake Hartwell, South Carolina, and the goat farm

Dwight Peck's personal website

Dwight Peck's personal website