You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

A look at some of the lake's natural wonders

(mainly glacial erratics) (and maybe a few sandbars) (& some ducks)

A mid-sized lake in the Wisconsin Northwoods, once entirely glaciated

Out to the boathouse 'harbor', late July 2024, this is our small fleet of one masterful though ancient bike with traditional yellow pontoons (reserved for this photographer), two brand new ones (green pontoons) that went into service two months ago (with little use so far), and the irreparable old warhorse now sitting up there on the drydock.

We're bound on a mission today, and Melvin's come along to see us off.

One yearns to take him along, perched on a pontoon, but if he were to panic (as surely he would), we could both end up swimming home, dragging the hydrobike along on the mooring rope.

Our mission, if that's the right word, is to inventory some the finest of our big erratic rocks, some of them submerged but most ranged along the shoreline, anchoring it in some places. Most or all of them were presumably left behind by the receding glaciers of the last Ice Age, but for some reason they're mostly found at the southern end of the lake, which seems counterintuitive (wouldn't proper glaciers recede to the north?).

Off we go, first round the main island in the upper lake, Adjidaumo (a name said to be pilfered from the name of a squirrel in Longfellow's Song of Hiawatha). Then down the long stretch into the southern bays.

Eyes on the World: 'Adjidaumo, the velveteen squirrel. American red squirrels, Tamiasciurus hudsonicus, look like russet velveteen plush toys, but in fact they are very aggressive. They have formidable teeth and claws.' The name is apparently from a Chippewa legend and means 'head foremost' or 'mouth foremost' for the way the squirrel descends trees (source).

+

+

None of our known erratics are the size of condo buildings, like many of those shown in the Wikipedia article, but they do have a presence of their own. This one's at the entrance to the little cove on the far side of the Tigertail peninsula.

And this one is nearby.

Now we're shifting over (past this grandiose second home) to the longish, undeveloped stretch of forested shoreline heading west towards the highway bridge.

That's just the boathouse; the mansiony establishment is out of view up left.

Here's a spur of the shoreline anchored by a little gang of boulders that won't being going anywhere soon.

We particularly like the boulders that seem to have trees growing right out of them, or nearly so.

This exercise in boulder double-teaming that tree is rather special to us, because . . .

. . . in September 2018 the tree got properly whacked by a stroke of lightning and is suffering still. One afternoon we were pedaling by, admiring the scenery, and the next afternoon, half the tree was gone. Wonders of Nature.

That's the elaborate complex of foundational blocks that are still holding up the sad, blitzed old tree.

This is a fairly healthy specimen, but it looks to be losing its grip on the shoreline, which is apparently receding behind it now.

To be honest, these exceptionally large rocks in the lake might not really be authentic 'erratics' after all, which are properly defined as boulders that have been transported by receding glaciers and dumped off amongst rocks of a different species. But whatever they are, they've certainly got moved round pretty convincingly.

Just as we're approaching the next string of developed housing built during an earlier generation, here's what's understood to be the largest (and ugliest) boulder on offer in the lake.

Just squatting there like Jabba the Hutt

Another biggish one near the first of the row of docks. There are very few boulders (and very few old trees fallen into the lake) fronting on the developed stretches of the lake; the homeowners seem to have found solutions of their own.

There's the highway bridge -- we're turning up to the right along Chase Island.

Chase Island is one big-rocks farm, in effect.

At the north end of Chase, like a turtle's head poking out of the shell.

And that too is poking its way out of the Chase shoreline, maybe soon to be left behind as everything else washes away behind it.

Moving back up north to the main lake, that's called Beaver Island on the rough map below, but which we've called Ryden's after its owner. It's connected to the mainland by the rocky sandbar on the left, and on the right it's got a massive jumble of rocks . . .

. . . like this. At the end of which, there is . . .

. . . this propeller snatcher. Fully submerged, invisible to racing skiboats, and when the water level's a bit lower than it's been the past few years, it accumulates an impressive assemblage of propeller scars all over it.

This one's just along the shore, across the strait east of Ryden's at the southern part of the upper lake.

And back into the cove behind Tigertail, there's this and . . .

. . . also this, another propeller-biter.

Another day, Melvin's come down to see us off again, and to . . .

. . . 'wet his whistle'.

(That's a bit of slang that's been in the language for more than 600 years, BTW).

No more boulders today, just stalking a patrolling family of ducks, trying not to disturb them, but . . .

. . . unsuccessfully; they're veering out of our path.

That's a 500 horsepower outboard engine, one which probably has no real purpose here, on a pontoon boat with a hull-speed a good ways short of that.

The owners here, a year or two ago, had a work team building a perfect stone wall along 200 meters of their shoreline to protect against the ravages of wake-surfer boats' depredations, and . . .

. . . when we pass by here, we like to take a quick photo of their own wake-surfer boat.

That's the funny little shrine at the end of the point at the entrance to Tomahawk Bay, with . . .

. . . its own permanent little frog.

Today we're looking for some of our more attractive sandbars and little rocky reefs.

This is the western end of George Island, featuring the corpses of the widespread growth of the hydrophobic tag alders that enjoyed the easy life when the water levels were way down.

We've been watching them die off annually with amusement, but these last survivors are the ones that had put down the most complicated roots. This rocky sandbar extends about 30m out towards the deepest part of the lake, at 30 feet.

Just beyond George's, we find Baby Leigh Island, state property though the state has probably forgotten all about it (a long-ago property tax issue), locally famous as frequently a favorite nesting place for a loon family. It's vicious rocky sandbar extends off to the left.

Approaching a little closer. The only good thing about the tag alders is that they provide, in some cases, the last warning of a reef to speedboat pilots glancing back at their waterskiers and sipping their margaritas.

We've sometimes asked old timers why the lake association hasn't posted the submerged boulders and reefs as dangerous, but the most common reply is that they've been told that if they posted some of the hazards and someone hit something unposted somewhere else, there might be liability issues. If nothing's been posted, it's just in god's plan for Nature, and also might discourage some of the day trippers from putting in on this lake.

The front end, or bowsprit, of the ship of Baby Leigh.

(Named back in the sawmill days, but the name's still passed down in the family.)

This is a rocky reef off Ryden's (or Beaver) Island (seen from the submerged erratic), and . . .

. . . that's the rocky sandbar connecting it to the mainland.

This is a rocky reef about 100 ft east of Raymond's or Crescent Island, almost standing to attention for us when we arrive in June and hanging on as best it can in September.

A better view of the reef behind the proscenium, extending back about 20 ft and requiring propellers-up to approach much farther.

Back to Adjidaumo, the main island: almost the last of the dry season surviving alders, and the best way onto the island, with a still-visible path up to the far end, but with hornets.

The shallowest part of the reef is at this end, but it extends semi-slopingly down 570 feet (174m) towards the eastern shore, so whether or not you lose a propeller crossing depends of how deep your propeller is. Hydrobikes droop theirs about 18 inches below water level, which means that we can cross (carefully) about here by hoisting it up for a little float with momentum.

At the other side of the island's crescent cove, there's this quaint little sandy area, good for a refreshing swim or a nap, unless an eagle is taking off from their nest high up above -- eagles are notorious for their gastrointestinal takeoffs.

The main island's main sandbar again, looking north towards Mussent Point.

(Ten years ago, we could punish ourselves by getting the hydrobike from Mussent Point out to the sandbar in under 8 minutes, 12 minutes in canoe. But no longer.)

A downed tree at Pradt's Point (as we call it), with Mussent Point peaking out from across the North Bay.

Pradt's Point also has a submerged point to make, which . . .

. . . extends out fairly far. Easy for canoes and kayaks, but hydrobikes are special.

Providentially, the hydrobikes have a guard down in front of the propellers to knock them back up on contact.

This is a narrow peninsula that protects the entrance to Tomahawk Bay, and it's got . . .

. . . the usual submerged extension eager to lure careless speedboat drivers, though in fact this patch is protected by NO WAKE bouys, and we've never seen anyone violate that order.

Just across that strait, looking into Tomahawk Bay, that's the other point, the one with the comical shrine on it, and . . .

. . . a sandbar sticking out about 12 feet.

Another day, we're casually progressing down the undeveloped west side below Ryden's, 25 July 2024, and we've overtaken a fairly populous family of patrolling ducks (more than can be expected by this time in the summer; there's always a certain about of attrition, alas).

They appear to have sensed our presence, and . . .

. . . they're breaking for wider spaces.

And regrouping, then . . .

. . . proceeding on their way into the middle of their lake.

Hey! Not so close.

Hey!

(In the end, they made it over to the Pink Island shore.)

And we ran into them a little later under the highway bridge.

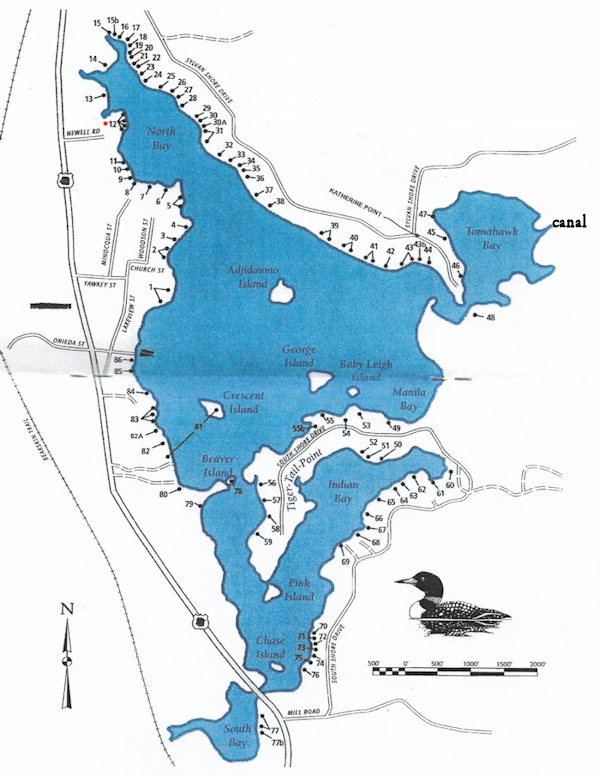

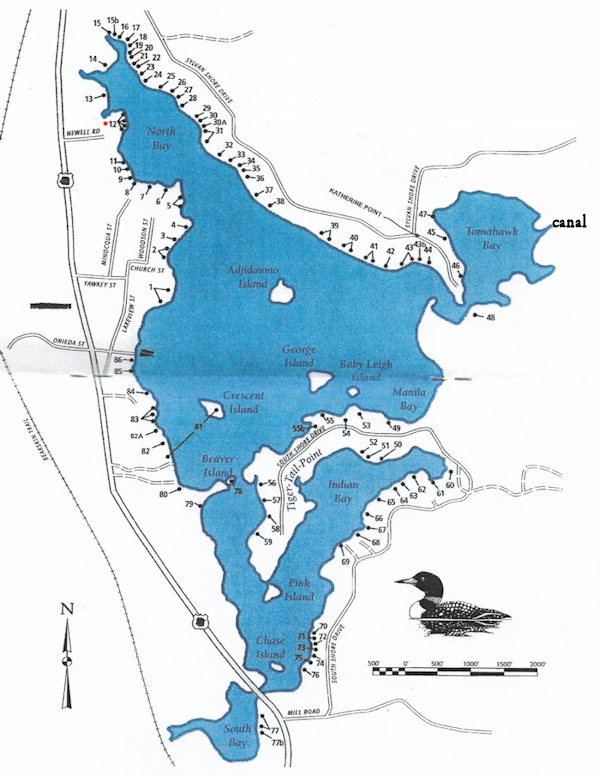

The Lake in the Wisconsin Northwoods

Mussent Point is at no. 12.

Next up: A birthday party and a batch of Pinus resinosa

On today's screens: the Guaita Tower, one of three overlooking San Marino, 2017

Dwight Peck's personal website

Dwight Peck's personal website

+

+