You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

We've just been sharing an edifying experience in the Basilica of Santa Pudentiana, and we're galloping down Via di S. Maria Maggiore to catch the Basilica di San Pietro in Vincoli, the Church of St Peter in Chains, before it closes (which is frequently at noon) till mid-afternoon, 21 October 2024.

We're ten minutes too late, or might have been except that this one closes at 12:30. We dash in eagerly.

Enormous! It's not entirely clear that St Peter actually visited Rome, as his influence on the early efforts of the apostles, along with James the Just, Christ's brother, was at first focused on bringing the message to the Jews, whereas it was St Paul who was devoted to spreading it to the Gentiles as well. But by the end of the 1st century and certainly into the late 2nd, it was understood by the early writers that he had joined Paul in Rome for form a church of converts there.

Early traditions said that he was crucified by Nero in AD 64, but according to Jerome and Eusebius, Peter died in the year AD 67–68, 25 years after his arrival in Rome in AD 42. The connection with the chains is based on the tradition that he was incarcerated in Rome and treated badly, in chains, prior to his execution. That's one of the two versions . . .

. . . the second is more complicated: that the church is sometimes called the Basilica Eudoxiana based on the story that the chains from Peter's earlier difficulties in Jerusalem were given by the Bishop of Jerusalem in about 438 to Aelia Eudocia, who sent them to her daughter, the wife of Emperor Valentinian III, the Empress Eudoxia, who then presented them to Pope Leo I the Great to be housed here.

Which led to a gradual melding of the two stories into a still better composite one. When Leo compared this chain with that of Peter's fatal imprisonment in Rome, the two chains miraculously fused into one.

In any case, the structure of the present basilica is essentially that of the 5th century church, and so this is one of the oldest church buildings in Rome. It evolved into an important pilgrimage destination, and thus was restored and improved by four popes in the late 8th to the mid-9th centuries. Given its size, it was often used for church councils, and Pope Gregory VII Hildebrand was elected here in 1073; it was he who changed the name from Saints Peter and Paul to St Peter in Chains. During the 'Babylonian Captivity' of the papacy in Avignon, the basilica declined, but a massive restoration was undertaken from 1448 through to Julius II's reign (1503-1513). The portico out front was added in 1475, but there seems never to have been a belltower, unless an earlier one fell down and wasn't replaced.

The layout is a common one, a Latin cross with a nave with two aisles, a transept and apse. The apse is large and comes from the original 5th century building. There was a monastery attached in 1475, but it was taken over by the government in 1873 for a college of engineering (which is still operating), though the original cloisters by Giuliano da Sangallo have been preserved.

A new high altar was finished in 1877, with a beautiful medieval-style baldacchino or ciborium by Virginio Vespignani. The frescoes around the apse walls, executed by Jacopo Coppi 'del Meglio' (1546-1591) in 1577, show St Peter liberated from the prison in Jerusalem and his chains being transferred to Eudoxia and then to Pope Leo.

Coppi also painted the frescoes in the semi-dome conch above with a cycle on the 'Crucifix of Beirut', which bled miraculously when desecrated by Jews, but nobody knows what that's got to do with anything here.

Until the restructuring of the sanctuary in 1875-1877, the chain was kept in the sacristy and brought out only on special days. To make it permanently worshipable, the floor under the altar was dug out, creating an open relic-space or confessio, with the chain in a glass reliquary made in 1856 on its own altar below the main one, reached by a double staircase. The chain is flanked by a statue of St Peter on the left, and on the right, the angel who sprung him out of prison in Jerusalem.

There is actually a small crypt just behind the chains shrine, reached by a small door on either side, which contains an Christian sarcophagus dated to the 4th century. It was used to house the putative relics of the 'Holy Maccabees', seven Jewish brothers who were tortured to death in the 1st century BC for defending the Jewish laws. The sarcophagus was gifted here for Pope Pelagius in the 550s. Archaeologists looked into the matter in the 1930s and discovered that there was only a collection of dogs' bones within, so with little publicity the crypt has been kept locked and inaccessible to visitors.

The present ceiling dates from the early 18th century, and the fresco in the central panel is by Giovanni Battista Parodi of Genoa, 'The Miracle of the Chains', 1706.

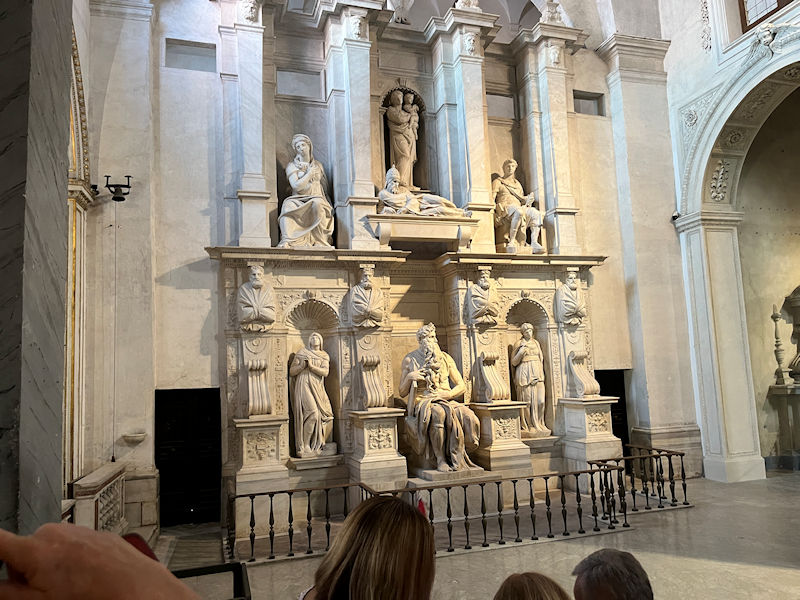

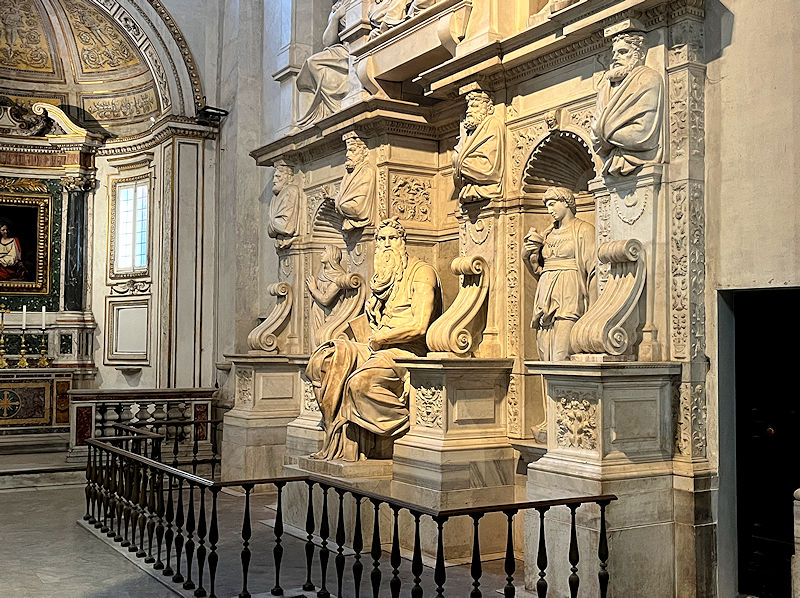

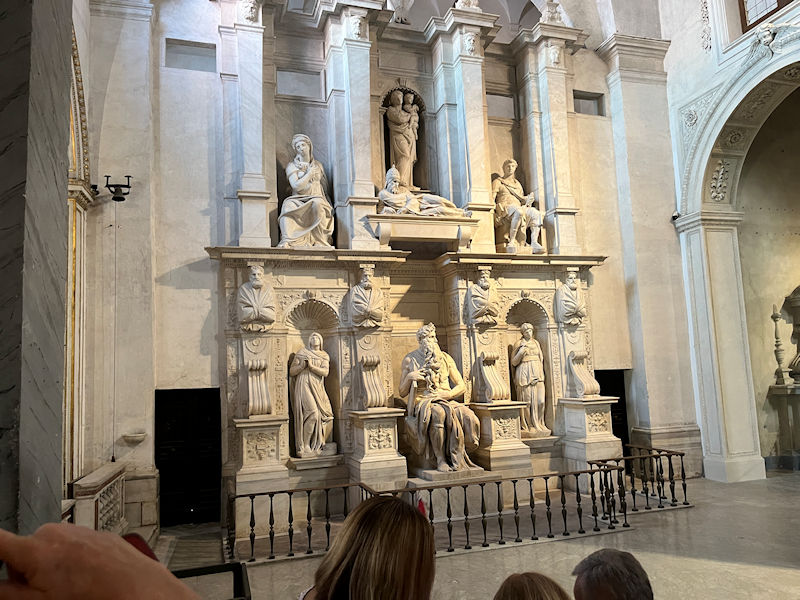

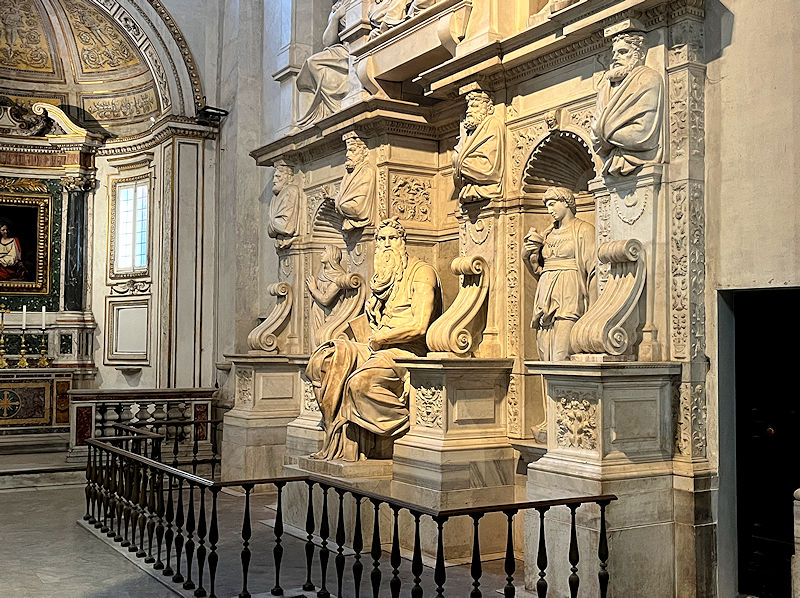

This is the celebrated feature of this church, the funeral monument of Pope Julius II della Rovere, which was intended for the new St Peter's Basilica but got planted here in 1545 instead, stuck out from the right wall at the end of the aisle. It's the completed part of a super-tomb project that Julius (the 'Warrior Pope', r.1503-1513) planned for himself to have some 40 statues in all. In 1505 Julius commissioned Michelangelo to return from Florence to complete the project in five years. The two fought regularly and the artist left town for safety, then agreed to come back to work on the Sistine Chapel, and only resumed on this project in 1512.

By the time Julius died in early 1513, only three pieces had been completed ('Rebellious Slave' and 'Dying Slave', both now in the Louvre, and this Moses), and a new contract was drawn up with the pope's heirs. In the 1520s he had time for a few more Slaves (now in Florence), and signed a new contract in 1532, but returned only in 1542 to what was by then defined as a wall-tomb, in effect a cenotaph or funerary monument since Julius is interred in St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City. It was completed in 1545.

That's Michelangelo's Moses, who's apparently just come down from Mt Sinai (Horeb) with the Tables of the Law that he got from God and, it seems, found his followers worshiping their own golden calf and got really, really angry. He's got horns on, which seems hilarious, but the consensus these days seems to be that it was not uncommon in medieval art and results from a mistranslation in Jerome's Vulgate Bible of 'beams of light' for the word for 'horns'.

The siting of the monument here is apposite because this was essentially the delle Rovere family's church (there are said to be seven delle Rovere cardinals here). The Moses is definitely Michelangelo's own, and the Leah and Rachel flanking him (representing the active and the contemplative life) are arguably either his but not his best, or by his pupils with his help on the drapery, or just by his pupils.

Pope Julius [whose monument this was meant to be] is dozing on a sarcophagus in the Etruscan funerary style, looking bored, with the Madonna and Child above him, attributed to Alessandro Scherano, a Sibyl to the left and a Prophet to the right, both attributed to Raffaello da Montelupo, both apprentices of the master.

This is an indifferent Madonna and Child with Angels as the altarpiece in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel, anonymous, 19th century.

The uplifting tomb monument of Cardinal Mariano Pietro Vecchiarelli, 1667

And this similarly themed tomb monument of Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini was erected 1705–07, with a grim sculpture by Pierre Le Gros the Younger.

A chapel altarpiece with an interesting 'Deposition' by Il Pomarancio (Cristoforo Roncalli, c.1552–1626)

The tomb of Nicolo (Nicolas) Cusano (1401-1464), the Italian humanist, by Andrea Bregno, 1464, featuring St Peter (with his key), an angel, and some chains.

The portico was added onto the ancient façade in ca.1475, and the story above that in 1578.

Inside the portico at the entrance is a bronze work by Canadian artist Timothy Schmalz, 'When I was Naked', whose other pieces we've been seeing all round Rome, made on the occasion of next year's Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy.

But we must have walked right past it.

The Piazza (and carpark) di San Pietro in Vincoli

The Scalinata dei Borgia adjacent to the Basilica, leading conveniently down from the Via Cavour.

There are stories about how the palazzo built over the steps, owned by the Cesarini family, was taken over by Pope Alexander VI Borgia in about 1493 and given to his putative mistress, Vannozza dei Cattanei, and that it was here on the steps that the pope's 'oldest son' Juan or Giovanni was assassinated in June 1497, then carried off and dumped into the Tiber. After the pope died in 1503, the palazzo was returned to the Cesarini family. The balcony in this photo even figures into at least one of the tales, none of which seem very plausible, but who knows?

Now a bit of a trek home. That's the Via degli Annabaldi down there, which dumps out into . . .

. . . the Piazza del Colosseo and, on the left, the Via Labicana up to the Lateran.

Past the Colosseum, the road becomes the Via dei Fori Imperiali, alongside the old Imperial Forum.

-- Need a souvenir photo taken?

(I seem to recall that these plastic-armored legionaries were banned from the Colosseum area some years ago, but seems not, or no longer. This is my favorite photo of the gentlemen at work.)

Even Roman legionaries deserve a coffee break from time to time.

Sentry duty

That's the Torre dei Conti, overlooking the Largo Corrado Ricci and the remains of the Forum of Nerva. It was built by a brother of Pope Innocent III in 1238 on behalf of their Conti di Segni family, strategically sited on the frontier between the Contis and the rival family, the Frangipani (tho' some say they were the Orsini). It was nearly twice as tall as it is now (which is 29m), but the upper floors were destroyed in earthquakes, and it was then abandoned until the early 17th century. In 1937 Mussolini donated it to his Arditi band of stormtroopers; that ended in 1943, but it's not apparent that there's anything going on in there now.

It's kind of a chilling, nasty-looking structure . . . never meant for fun or relaxation.

Similarly, that's the Torre delle Milizie up the hill a bit, which means that we've locked ourselves onto the wrong side of the Forum area.

So we retrace our steps and get back onto the Via dei Fori Imperiali.

A stroll along beside the Trajan Forum, just across the road from the larger Forum leading towards the Colosseum.

The concave buildings with a line of windows was once the Market of Trajan. The building with the red flag and the generous loggia is the Casa dei Cavalieri di Rodi (House of the Knights of Rhodes), since 1946 the home of the charitable Sovereign Military Order of Malta, one of the organizations claiming to be the descendants of the Crusader order of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem, the Hospitallers.

'When I was sick', by the Canadian sculptor Timothy Schmalz: 'The original cast bronze is permanently installed at the entrance of Santo Spirito Hospital'.

With a little time to kill on our last afternoon here, we're exploring whatever lies above our grand staircase.

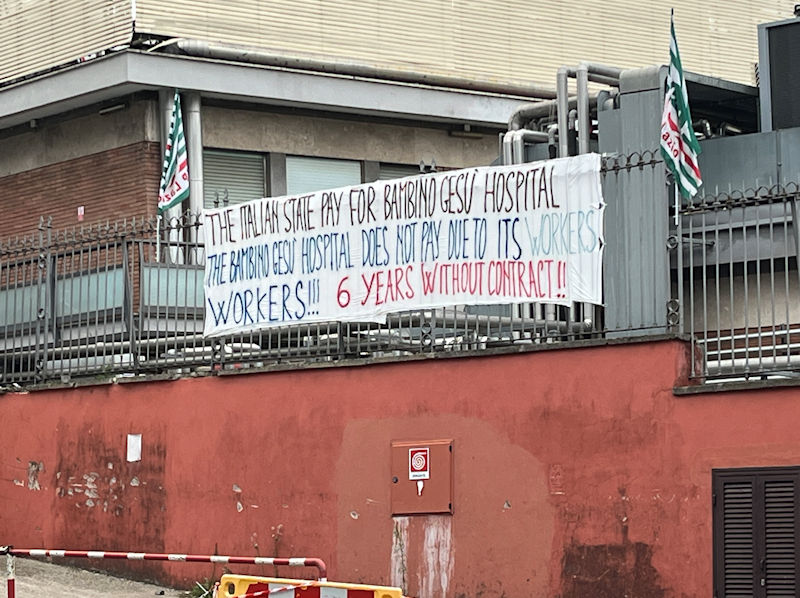

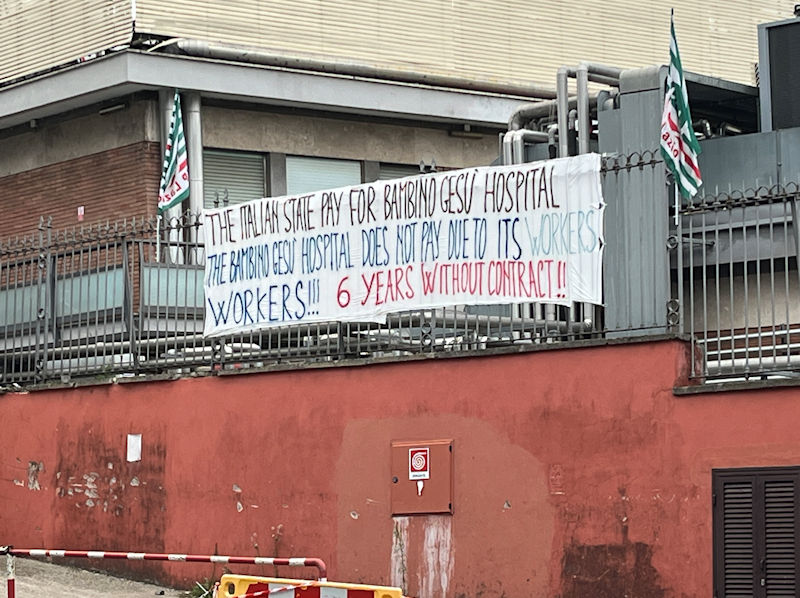

There is a hospital and religious complex stretching from this far up the Passeggiata del Gianicolo to the pediatric hospital Bambino Gesù, and there are some fairly direct staff complaints hanging out front.

The Chiesa di Sant'Onofrio al Gianicolo (including the 'Holy Shrine Madonna with Child and Saints John, Gregory XVI and Dorothy')

The tomb of the famous 16th century epic poet and unfortunate bipolar person, Torquato Tasso (1544-1595), is said to be in the convent here.

The scene from a lookout point on the way up the road

The pediatric hospital Bambino Gesù, with problems on its hands

Heartfelt complaints, not uncommon nearly everywhere these days

The Vittorio Emanuele II monument by the Piazza del Campidoglio

Just across the road from the Bambino Gesù, this is the Faro degli Italiani d'Argentina (the Lighthouse of the Italians in Argentina, aka the Faro del Gianicolo or the Faro di Roma), created in 1911 by the architect Manfredo Manfredi near the site of the defense of Rome in 1849 by Garibaldi's Republican army against the far superior French army's siege (Anita Garibaldi's statue is just 150m farther up the road, and Garibaldi's 200m beyond that).

The info panel says that the lighthouse was donated to the city by Italians living in Buenos Aires on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Italian Unification.

In addition to the official information plaque, there is this, placed by the Argentinian embassy to recall the 'military coup' against Peron in Argentina on 24 March 1976. 'Never again!' in Spanish and Italian.

We're down to the Via di Sant'Onofrio again and back down to our stairs.

It's almost time for dinner, at the Trattoria Polese this time.

Back up to the Corso di Vittorio Emanuele II, and turning right

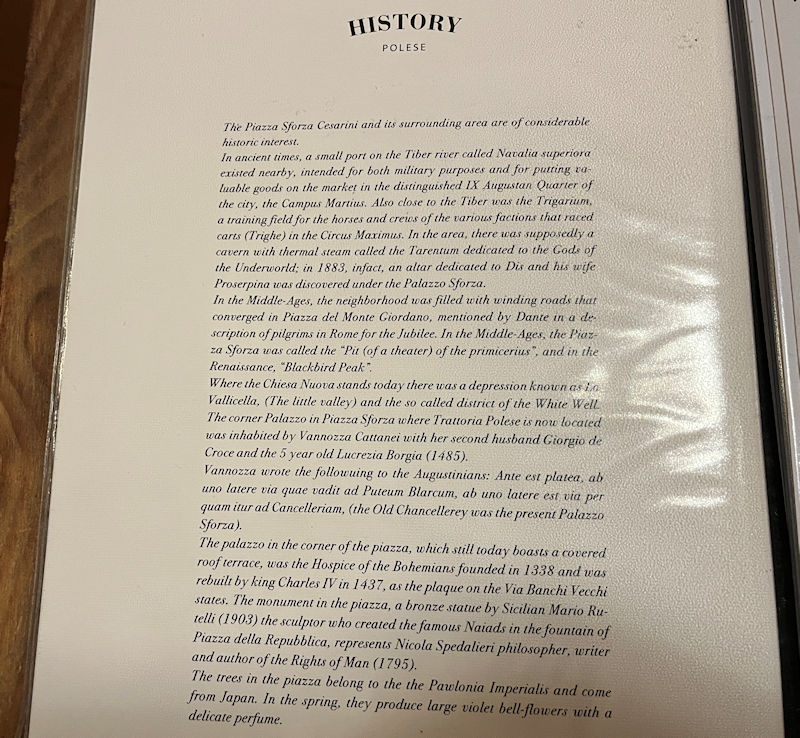

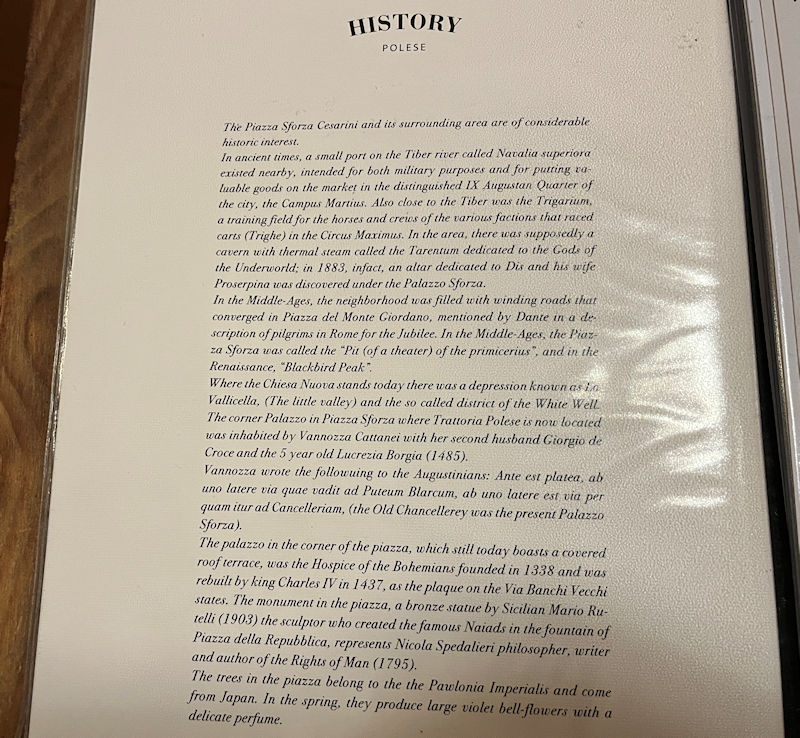

The Polese was our favorite restaurant a few years ago (and it's quieter inside than out in the park). We spend a lot of time scrutinizing the menus wherever we go, some for the culinary opportunities and . . .

. . . others for the historical background.

(Lucrezia Borgia slept here!)

Dinner was very good, as usual.

And everybody's happy.

We probably should have been coming here every night, but the Sor' Eva was so much closer.

Maybe next year, who knows?

Next morning, we're getting organized.

Kristin's dashing out to meet the taxi.

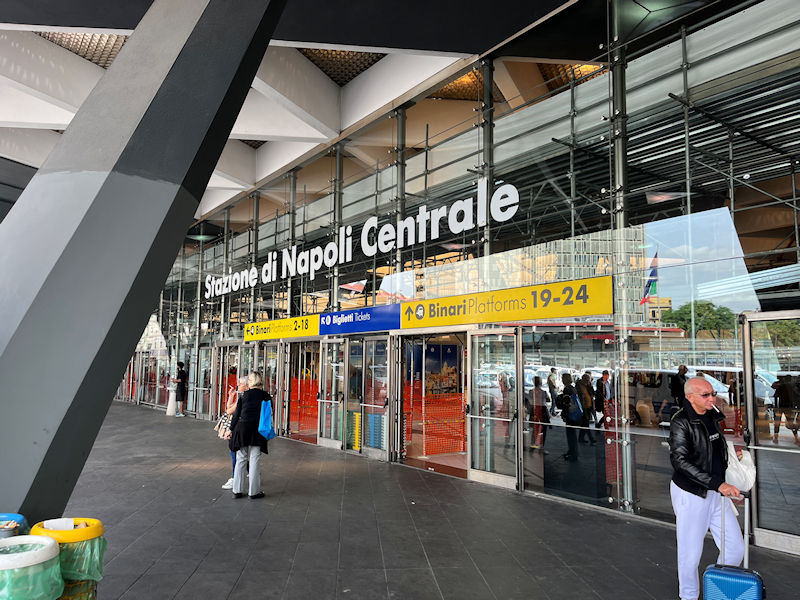

We're looking for the high speed train from the Termini rail station to Naples Central

Dwight Peck's personal website

Dwight Peck's personal website