You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

We're on our way out to visit the Basilica of St Paul Outside the Walls, which as the name suggests lies near the Tiber about two miles southwest of the centre city, where in AD 65 or 67 the Christian proselytizer Paul the Apostle was beheaded by the authorities. According to tradition, since he was a Roman citizen his body could be buried in the sepulchral area along the Ostiense Way outside the Aurelian Walls of the city, and a memorial that was set up for it soon became an object of veneration for the growing Christian population.

That's the place. The Emperor Constantine commissioned a first basilica over the memorial, which was evidently consecrated by Pope Sylvester in 324, and during the 4th century the body was moved into a proper sarcophagus (excluding the head, said now to be in the Lateran church). The Emperor Theodosius began a much more impressive basilica in 386 and improvements continued into the 5th and 6th centuries, when a new altar was built over the saint's sarcophagus.

There were various ups and downs in the life of the place over the centuries, including a sacking by the Saracens in the 9th century, the addition of the present Benedictine monastery built onto it in the 10th century and its beautiful cloister built in the early-mid 13th century. In 1823, however, a terrible fire destroyed a great part of it -- reconstructions were immediately begun, with the intention of recreating it just as it had been, with the best of the improvements (like the mosaics). That work continued into the 20th century, but there seems to be some difference of opinion about how realistically that plan could have been carried out. In any case, it's a pretty amazing place now.

It appears that we'll be well looked after whilst we're here.

St Paul's is one of the four major papal basilicas in Rome, along with Saint Peter's, St John Lateran, and St Maria Maggiore, and one of the Seven Pilgrim Churches. It's included in the UNESCO World Heritage List (1980), as extended in 1990.

We're entering by the 'Quadriportico' with its 150 columns, which was added in 1928, and a façade, with apparently some of its original mosaics, recreated by a Luigi Poletti as part of the restoration works.

The mosaics on the upper façade show Christ flanked by Peter and Paul, the two patrons of Rome, and beneath them the Sacrificial Lamb with the cities of Bethlehem and Jerusalem on either side. Across the bottom are said to be the Old Testament's major prophets: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel.

And that's St Paul his own good self -- the 'Church Militant' indeed -- not the famed letter-writer informing early proto-Christian congregations how they need to conduct themselves appropriately, rather an angry looking chap waving a long sword. This disconcerting piece was sculpted by Giuseppe Obici at about the time of the restoration's reconsecration in 1854.

The central door is closed off, and the one on the far right is the Holy Door, which is only opened for pilgrims during the years of Jubilee. But they're going to let us in by . . .

. . . the door on the left. It's the 'Pauline Door', created in 2008 with four scenes supposedly from the life of St Paul for the 'bimillennium of the birth of St Paul'. We'll scuttle past that right in to see the good stuff.

Ooof! The resurrected post-1823 basilica is said to reproduce the dimensions of the pre-1823 structure of one nave with four side aisles, ca. 132m long, 65m wide, and 30m high.

Good grief! Now with 80 columns and an impressive wood-and-stucco ceiling, all from the 19th century, but . . .

. . . intended to recapture the original edifice, as well as possible.

The pictures along the top illustrate scenes from the life of St Paul, whilst . . .

. . . the medallions in a row all the way round are intended to show a portrait of every one of the popes to date (266, we're told). Most of the original frescos were destroyed but they've been replaced by a full load of mosaics (including Pope Francis), though for a great number of the early ones they must be fanciful. There are only a few spaces left for new popes, and one of the articles on the subject recounts a not uncommon superstition that when the last pope-space is taken, the world will end.

We'll dash up now to visit the apse and altar area, if we can slip past . . .

. . . another maddened looking Militant Christian, with his huge sword and his list of urgent commands for us.

That fine ciborium, or baldachin, covering the altar of the 'confessio', dates from about 1285 and happily escaped the 1823 fire. Next to it is the marble Candelabro del Cero Pasquale, or Easter Candle, also made in about 1170 by Pietro Vassalletto, an early member of a famous family of sculptors, who in fact created the fine monastic cloister out the back here.

The lower range features monstrous beasts and other stuff mentioned in the Book of Revelation and, higher up, scenes from the life of Christ, with his ascension etc., and at the top 'a cup that contains the light of Christ'.

(Kristin is pausing to recall our ongoing collection of photos of her sticking her finger into the mouths of lion statues. That's here.)

Christ the Pantocrator and his entourage

Two layers of early altars built on top of St Paul's sarcophagus sort of lost it for a while, it appears, but in 2006 Vatican archaeologists confirmed that there was white marble sarcophagus down there, about 4½ feet below the altar, now reached by either of these two short stairs. 'In 2009 Pope Benedict XVI announced that radiocarbon dating confirmed that the bones in the tomb date from the 1st or 2nd century', so maybe that does house St Paul his own self (sans head).

The guide to the floor plan mentions the 'Tomba di S. Paolo e catena', so presumably we're meant to understand that the slender item in the screen facing onto the tomb were the worthy apostle's original prison chains, or something.

So there's one side of his sarcophagus (have a good look); after its discovery, a large window was carved out to allow the credenti to view it. Up beyond this is the 'papal altar', intended only for the use of actual real-life popes. Non-papal officials apparently must use 'the altar of the confessio' out front.

A look along the right side of the transept, and . . .

. . . and the view back out through the triumphal arch into the nave.

Another view of the football-field size nave, this one from near the papal altar, alongside the sarcophagus stairs, and . . .

. . . the arch from this side, with St Paul on the left and Peter with his key on the right.

The apse mosaic itself, commissioned by Pope Honorius III (Savelli) in the early 13th century, has been largely restored based on surviving tesserae after the 1823 fire but is impressive nonetheless. Christ on his throne is flanked by the apostles St Peter and St Andrew to his left and Luke the Evangelist and St Paul to his right, and across the bottom the other apostles are ranged with two angels with an empty throne between them and Pope Honorius just to their left (with his name inscribed in tiny white on black next to St Paul's foot).

This fine piece, which at first puzzled us, turns out to be (obviously) an acquasantiera or holy water font, normally placed just inside the church entrance and seldom so artistically impressive, and present (I've been told) inside every Catholic church. The idea is that the serious churchgoers can dip their fingertips into the water that's been blest before making the sign of the cross and proceeding into the church.

This one is stuck in a corner of the right transept next to the 'Chapel of St Benedict', and here the demon appears to be seriously discomfitted by the blessedness and the other figure, a cherub or little kid, has a quiet I-warned-you look. It appears that it was created for this church in 1860 by one Pietro Galli of Rome (1804-1877) (though we've seen one description, without citation, to the effect that it was made 'for the Duchess of Bauffremont, which she then donated to Pius IX in 1860').

The 'Chapel of St Benedict', commemorating the 6th century founder of western European rule-based community monasticism, was built by Luigi Poletti as director of the post-1823 reconstruction. The saint is holding his crozier of authority in one hand and his seminal Benedictine Rule in the other. The marble columns were discovered in the ruins of Etruscan Veii and donated by Pope Gregory XVI for the chapel.

On the other side of the apse mosaic and altar is the 'Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament', supposedly housing a miraculous wooden crucifix which in the 14th century 'turned its head towards St Bridget while she was praying in front of it' (presumably Christ's head is meant). There are also a 13th century mosaic image of the Madonna and child over on the left and a medieval wooden statue of St Paul on the right, much nicked over the years by pilgrims seeking relics.

We're headed now for the monastery's cloister and the chapel of relics, for a small fee, and then the snack bar.

The cloister was built in the early 13th century by members of the Vassalleto family of leading Roman sculptors of the time, and members of the contemporary Cosmati dynasty are said to have had a hand in it as well.

The beautiful ambulatory running round the four sides of the garden; the monastery, its cloister, and its chapel of relics and paintings seem all to have escaped the fire of 1823 entirely.

The amazing twisted columns are mostly alternating with others decorated with mosaics, each pair supporting a rounded arch, all the way round the four sides.

-- Wait a second; we're being observed.

-- Oh, that's okay then.

We move on now to the Cappella delle Reliquie e Pinacoteca. (Visitors of a more modern sensibility might not really want to know what's in those reliquaries.)

St Sebastian between Sts Michael and Roch (pointing to his bubo)

(by Antoniazzo Romano [Antonio Aquilio], between 1460 and 1510)

Madonna and Child with Sts Benedict (rule), Paul (sword), Peter (key), and Justina of Padua (said to have been martyred in AD 303, stuck with a sword) (by the same artist)

Justina again, normally shown as here with her martyr's palm, a book, and stuck with a sword

(attributed to the 'Circle of Antoniazzo Romano - Umbrian School, 16th century')

St Paul (again with his trusty sword) and St Peter (with his heavenly key)

(also

'Circle of Antoniazzo Romano - Umbrian School, 16th century)

Kristin worships box plants (perhaps because 'the Boxwood represents longevity and immortality'?).

-- What's up there?

-- Just more monastery.

There are lots of bits and pieces on display here, many being fragments from the destroyed basilica and . . .

. . . a collection of sarcophagi as well. At least one (perhaps this one) is said to represent the doings of the god Apollo.

And one that appears to feature Christ being tormented.

We're on our way out now, stopping only to admire (and imitate) this piece, called 'When I was in prison', by the Canadian Timothy Schmalz, made for Pope Francis' Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy of 2015-2016.

Ciao for now

A pretty amazing place -- an awful lot of churchgoers' money must have gone into that over the centuries.

Heading home, and passing the Theatre of Marcellus, and . . .

. . . crossing over to the Tiber Island (the Isola Tiberina), with this side of the river evidently undergoing some maintenance.

We're on the Ponte Fabricio, built in 62 BC, the oldest Roman bridge still standing . . .

. . . with the Church of San Giovanni Calibita on the right and the Tiber Island Hospital extending to the far end of the island, and . . .

. . . the Basilica di San Bartolomeo all'Isola and the Martyrs' Monument on this side.

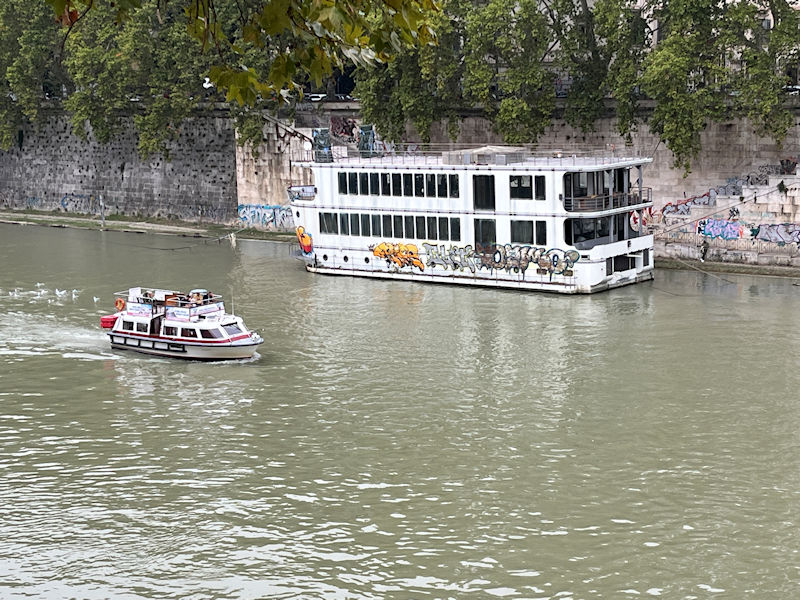

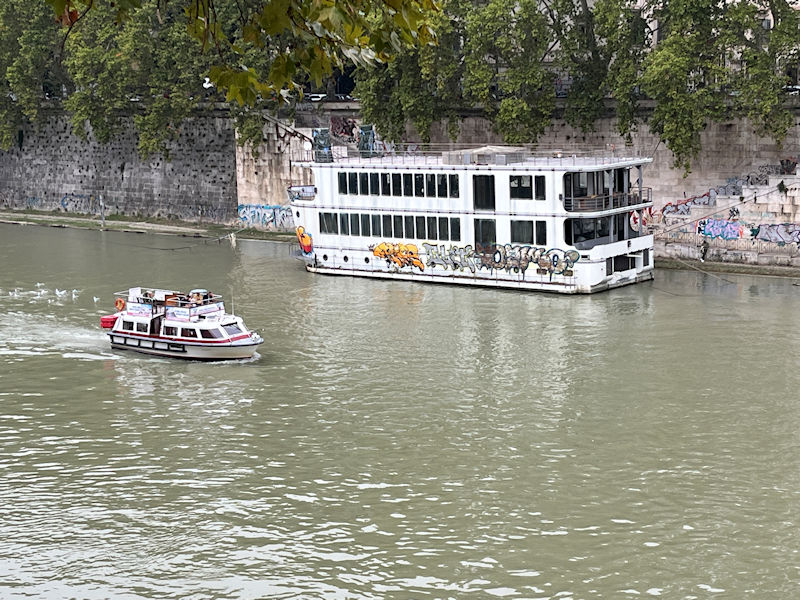

The river on this side of the island looks like its doing fine . . .

. . . flowing briskly past the Pons Aemilius, dating from the 2nd century BC, now called the Ponte Rotto, the Broken Bridge.

And here's why the other side of the river round the island looks so stagnant -- serious works going on near the Ponte Garibaldi.

In fact, there is a vast assortment of serious fix-ups and clean-ups going on all over the city at present, all in preparation for next year's Jubilee Year. We met no one in a week who wasn't fairly well irritated by the disruption caused by the Church's newest fundraiser.

Now we're galloping along past the Fontana di Ponte Sisto, bound beside the Lungotevere to get back and dress for dinner.

More Tiber fun

Next up: the Basilica of San Clemente and its subterranean pagan temple

Dwight Peck's personal website

Dwight Peck's personal website