You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

We're not based in Europe anymore, and we've struggled through the covid-19 lockdowns like everyone else, so we haven't set foot in Italy since February 2019. Now we're making up for lost time with mad sightseeing, but missing the cats even more sorely as the days fly by.

23 November 2022 begins in our pleasant newly assigned hotel room under the roof of the Hotel Guiderocchi, with a plan.

We leave the hotel out the back door, because . . .

. . . we've been told that there is a walkable route up to the Fortress Pia at the top of the Annunziata hill, here at the southwestern edge of the old town. It's probably 'walkable' indeed in the most technical sense of the word, but . . . ooof.

We've made it this far, there's no turning back now. That young lady below has passed us several times, in both directions, at a full gallop. Endlessly up and down the 'Scalinata Annunziata'.

Topping out on a road leading to the Chiesa della Santissima Annunziata, now undergoing lavori di somma urgenza, works of the highest urgency, apparently because of seismic events of 2016.

This is the Parco dell'Annunziata facing out from the convent complex, including a little playground, with the belltower of the Church of Saint Angelus Magno on the roadway down below.

This was once a vast medieval complex built over the remains of old Roman buildings, including a hospital until 1250, when St Peter the Martyr handed it over to some Augustinian nuns, who added the smaller of the two cloisters. From 1481 to 1861 the convent and church were governed by the Friars Minor Observant of Ascoli.

From 1882 the complex became the first agricultural college in Italy, but in 1933 it was converted to an institute for orphan girls; thereafter it was abandoned for a long time, during which a number of artworks by Crivelli and others were looted, now in the National Gallery in London and the Louvre.

This is the larger of the two cloisters and it's fitted out as a college level educational institution, as the headquarters of the School of Architecture and Design, 'Unicam' (University of Camerino), and the property is part of the heritage of the Fondo Edifici di Culto.

The entire religious complex, behind a portico with eight arches, is made up of a vast building which includes the former church, the former convent, the former refectory of the friars, and two cloisters. The main cloister dates back to the 14th century, and the minor one has an ancient well from the 15th century.

It's time for lunch.

Student groups are studying, conversing, and having lunch round the four walls of the cloister. Leading off from here and from the loggia above are classrooms, lecture halls, and offices, and there by the door in the far corner . . .

. . . is Kristin waiting for our lunch.

That's the 15th century well in the smaller cloister, and . . .

. . . that's the playground (the parco giochi).

A brief stroll through the park, postprandial

The belltower of Saint Angelus Magno, centered on the complex of the Università di Camerino Scuola di Architettura e Design - S Angelo Magno

The view over Ascoli from the park

It's time to move on and find this storied Fortezza.

Amongst all of the university ambience, it appears there are still some religious institutions at work here, as two kind gentlemen dressed in monk suits have been advising us of where we're meant to go next.

This way, in effect

A little road that winds up the Colle dell'Annunziata -- it's called the Strada per Rosara and continues at this height off to the west, but in about 800 metres it will also turn back up a level on the Viale della Pia Fortezza.

Soon we should intersect the city walls coming up through the forest.

Oh man. We did the right thing last evening by turning back down that crappy little path.

Somebody's evidently serious about this, but there's no sign of recent work on it.

Now we'll proceed on our way along the road, not . . .

. . . on the continuation of the crappy path.

We'd been given the impression in town that there's not much of this thing left to see, but this is already impressive. That gateway only leads round to a main entrance at the far end.

That, presumably, is where we might have emerged from the mud, had luck and better timing been on our side. As if!

At the very end of the information panel near the fort, someone has added this in a bold red font (in Google Translate): ''In the path . . . there are some stretches very difficult to walk over. Pay attention: it is practicable only if an adult is present and it's not recommended to unskilled people'. Now you tell us.

Through the single gateway on this side and round to the entrance on the eastern side. We're informed that at the top of this local hill, at 600m altitude, there were Piceni fortifications here from earliest time, destroyed by the Lombards in 578, rebuilt in the period 1185-1195 and further strengthened by Galeotto Malatesta in 1349 during his hostile control of the city. Over the years thereafter, however, it fell into disrepair.

With the warnings of the Spanish/Imperial incursions into and occupation of the Papal States in 1556 and 1557, as part of the 'Italian War of 1551–1559' [in this region perhaps called the 'Tronto War': unconfirmed], Pope Paul IV Carafa wrote up a brief for the strengthening of these fortifications, and 1561 Pius IV Medici started the works, which were completed in 1567. (It's old Pius who's donated his papal name to the Fortezza Pia.)

That's the formal entrance in the rather odd shape of this rocca -- under the cover on the right are archaeological excavations, perhaps ongoing, but not obviously so.

In 1799 the fortress was largely dismantled by Napoleon's troops, and again fell into disrepair. On the information placard at the entrance to the first gate, there is a paragraph devoted to the subsequent restoration efforts -- it covers the purpose of the work on 'this irreplaceable value historical monument' and cites the participants in the financing of the work and the firm carrying it out, but it doesn't mention any dates, and it's a fairly beat-up old panel.

That's presently the main and probably only entrance, apparently closed up tight.

Yep.

It's too bad, it would be good to see what sort of structures and layout remain inside.

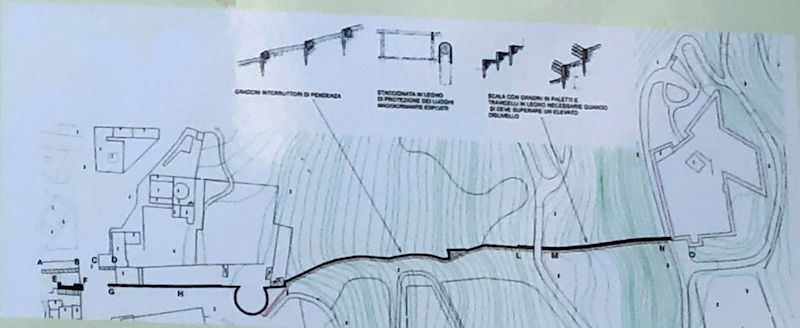

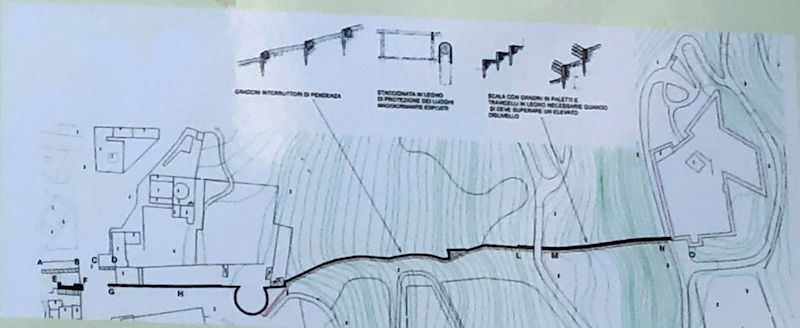

In any case, this schematic drawing from the information placard shows the present rather odd shape of the fortress on the right, and the connecting wall between the rocca and the circular bastion and Porta Romana down below.

We will next take a stroll round the outside of the walls.

It would certainly be a laudable enterprise to get this thing up to safety regulations and open it up to the inquisitive public, like us.

It's hard for us laypeople to guess whether the odd shape of the thing was original, for either topographical or military reasons, or simply a rebuilding of only the parts that were left over from that lifetime of desecrations.

One must confess that it's awfully tempting to scramble up there and see if there might be a sneaky way in. But we'll leave that for another day.

It must have been a fairly formidable defense work in its time.

We pass the beat-up old placard and retrace our steps to the far end, where we noticed a stair down that eastern side of the hill.

We're back onto an upper extension of that forbidding Scalinata Annunziata, with a long way to go down it.

This noble edifice sitting out here alone is identified as the Torre del Cucco, a tower that was part of the church of S. Pietro del Cuculo from the 1300s.

There's doubtless a story there, but there doesn't seem to be any church of that name anywhere round here at the moment. (And 'St Peter of the Cuckoo' sounds so improbable anyway.)

Downhill is always harder than uphill these days. And slower.

Passing the level of the Chiesa della Santissima Annunziata

At the head of the main staircase, our prospects look dreadful. But luckily . . .

. . . there is a workaround for at least part of it.

Seldom so pleased to be back on flat ground

Dwight Peck's personal website

Dwight Peck's personal website