You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

We're not based in Europe anymore, and we've struggled through the covid-19 lockdowns like everyone else, so we haven't set foot in Italy since February 2019. Now we're making up for lost time with mad sightseeing, but missing the cats sorely all the while.

Joe and Teny are off home to Switzerland, 14 November 2022, and we're on a city bus on the

Passeggiata del Gianicolo, up the Janiculum Hill and especially to its Garibaldi monuments. This is out the bus window paused at the 'Terrazza Panoramica' in front of the pediatric hospital about a third of the way up the hill.

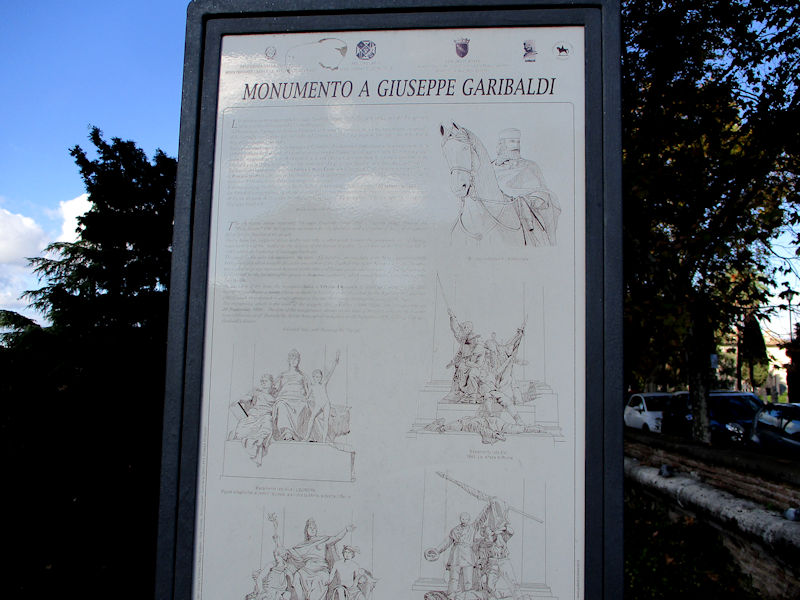

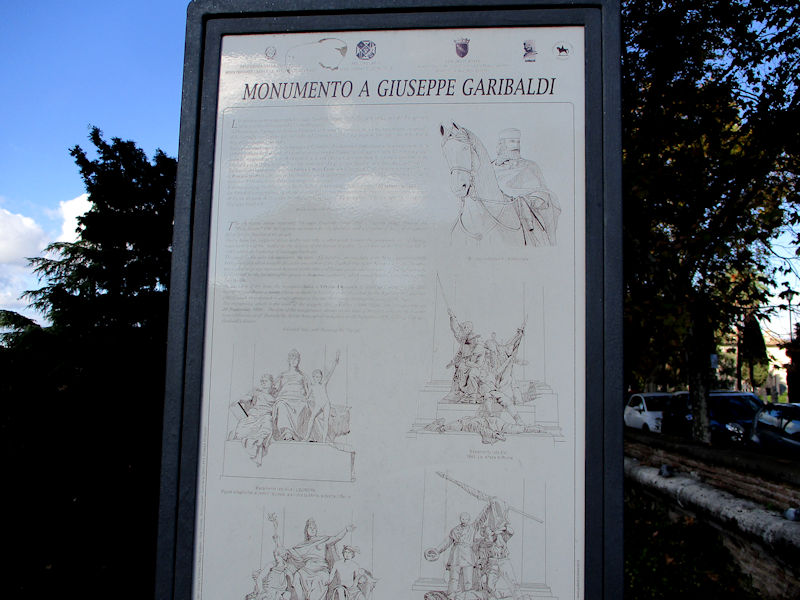

Now we're up by the Piazza Giuseppe Garibaldi, downing panini on a park bench and preparing to admire the equestrian statue of Garibaldi erected by a grateful nation. It was inaugurated on 20 September 1895, a date chosen to recall the seizure of Rome by the Italian Army in 1870, 'fulfilling Garibaldi's dream' of completing the creation of the present unified state ten years after all but papal Rome and Venice had been included.

Here's a description of the reliefs dramatizing the great man's career from his adventures as a revolutionary commander in South America, to his unsuccessful battle defending the Janiculum against the besieging French army in 1849, to his liberation of Sicily and southern Italy with his Expedition of the Thousand in 1860 -- however . . .

. . . at the moment the monument is shrouded in tarps for some kind of maintenance or repairs, and we're brokenhearted. So we've gratefully borrowed this photo by Sergio D'Afflitto, 2011, under Wikipedia Creative Commons.

We're moseying back down through the commemorative park towards the equestrian statue of Garibaldi's first wife Anita, past a host of busts of people who were instrumental in the defense of the hill by the army of the short-lived Roman Republic in June 1849, as well as more of them representing those who were otherwise important in the creation of the unified, secular state, such as members of Garibaldi's Sicilian Expedition in 1860.

This, for example, is 'Garibaldi's Englishman', the lawyer John Whitehead Peard (1811-1880), a colonel in the 1860 Expedition. It's not easy to find a reliable figure for how many busts are presently here; there were as many as 228 by 1860, it appears, but nothing like that many now. The first placements were made in the late 19th century, but restorations were made in the 1960s, and some new ones were added for the Jubilee year 2000. The best figure for the present crop on the hill seems to be 84 -- Wikipedia has a generous listing of some of them, with some information about the subjects, here.

Raffaele Cadorna (1815-1897) commanded a volunteer engineer battalion in Lombardy in the 1848-49 war and served with distinction in subsequent actions, including those against the Austrian occupiers in Friuli in 1866. He commanded the invasion of the Papal States and capture of Rome in 1870, completing the unification of Italy. The surname is unfortunately more familiar now because his son Luigi was the overall commander of the Italian Army on the northeastern Isonzo Front from 1915 until he was removed from duty in 1917, following the disastrous rout at Caporetto, with 275,000 Italian soldiers taken prisoner. (His own son, however, Raffaele Jr., was a famous commander of the Italian Resistance against the German occupiers after 1943.)

Here's what we've come to see, the 1932 statue of Anita Garibaldi. She was born in 1821 in the Kingdom of Brazil and joined up with Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1839 as he was fighting for the separatist rebels in the 'Ragamuffin War' (1835-45). She fought beside him, with sword and pistol, in several battles, but at the Battle of Curitibanos they became separated and she was taken prisoner. The imperial guards allowed her to search for him on the battlefield, with no success. She then escaped and evaded recapture, though her horse was shot, and she wandered alone for some days before being rescued and reunited.

Anita and Garibaldi moved to Montevideo in 1841 and were married in 1842, with four children being born there. She accompanied him to Italy (and left the kids with his mother in Nice, now in France) to join in the revolution against the Austrian Empire and was active amongst his 'red shirts' in the defense of the Roman Republic here against the French army's intervention for the Pope. When that failed they fled with a diminishing number of followers over the mountains towards free Venice, stopping at San Marino, where the town fathers tried to negotiate safe passage for them with the Austrian army (see note at the bottom of this page).

Anita by that time, however, pregnant and increasingly ill with malaria, died in their temporary hideout in the Comacchio Lagoon near Ravenna, and Garibaldi was forced to leave her burial to local partisans and eventually make his way to safety on the coast in Tuscany.

This relief on two sides shows Anita guiding a squadron of partisans across the pampas in Brazil. At the foot of it, there is this plaque:

Anita's remains were located and interred here.

This panel shows Anita searching for Garibaldi in vain amongst the fallen soldiers after the Battle of Curitibanos in southern Brazil, January 1840.

And here is Garibaldi carrying the malaria-stricken Anita, six months pregnant, in their flights from Austrian Army pursuers.

That's the prison just below us in Trastevere, the Carcere di Regina Coeli.

And there's Vittorio Emanuele II's typewriter.

Here's a bust of General Türr, a 'Garibaldino' from Hungary.

Following our wanderings amongst the various hero-heads, we boarded the wrong bus and spent the next few hours roaming all about the suburbs before finally ending up back downtown.

Brisk street commerce

The next day, 15 November, having survived yesterday's afternoon on a jolting bus all over the Monteverde suburbs, we're up by the Roma Termini, the main rail station, hoping that we're about to come upon the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore. Somewhere round here.

Crossing the top of what becomes the Via Panisperna down to the Piazza Venezia

There, facing west onto the Piazza dell'Esquilino, is the apse-end of the Basilica Papale di Santa Maria Maggiore, or the Church of St Mary Major.

We're passing round the side of it towards the front door.

The Piazza di Santa Maria Maggiore and the Fontana of the same name, with its 'Colonna della Pace' (the last survivor of 8 columns from the ancient Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine, built in the Forum by those two emperors in the early 4th century and destroyed in earthquakes of 847 and 1349; it was transported up here in 1614).

The imposing front of the basilica -- The present church was consecrated in 434 (after it was decided at the Council of Ephesus in 431 that Mary was actually the 'Mother of God'), and the core of it remains, despite further construction works and damage from the 1348 earthquake. Much of the interior and its altars were renovated in the late 16th & early 17th centuries, and the impressive façade with its loggia up top was added in the 1740s.

We need to cooperate with a little metal detecting before we can get inside -- fair enough.

The ponderous 18th century loggia

Neat floors

The nave is big, and the columns are ancient and many. The coffered ceiling was said to have designed by Giuliano da Sangallo and to have been gilded with gold handed in to his bosses by Christopher Columbus and passed on by Ferdinand and Isabella to Alexander VI, the Spanish pope.

The high altar and the famous mosaics, virtually unrecognizable here.

This is our favorite representation of a pope -- it's Pius IX, the chap (venerated as 'Pio Nono') who poped from 1846 to 1878, during which time he was able to excommunicate all of the reformist liberals of the brief Roman Republic in 1849 and talk the French into sending their army to Rome to put him back on his throne; make Mary's Immaculate Conception the official dogma; condemn all forms of modernism and liberalism as sins; and convince the Church Council that the pope, speaking as pope, is always Infallible. He was beatified by John Paul II in 2000.

This is our photo caption from a visit in 2006: 'Pio Nono, our longest reigning pope (1846-1878), now presiding in Santa Maria Maggiore. The sculptor caught him perfectly and did him no favors. He really does look like The Guy Who Got the Loot and You Can't Get It Back! "Thanks again, Lord, for Everything, heh heh heh!"'

Pio Nono is planted at the entrance to the Crypt of the Nativity under the main altar, which features the crystal Reliquary of the Holy Crib, or manger, of the nativity of Jesus. The crypt (we're told) also holds the remains of Jerome, the 4th century fellow who translated the Bible into Latin, the so-called Vulgate.

It's time to leave His Holiness to his reflections and ascend out of the crypt again.

As noted, the basilica is especially known for its grand mosaics, but they don't show up very well in these photos.

This is the Sistine Chapel and Oratory of the Nativity ( it's the Pope Sixtus V 'Sistine Chapel', not the Pope Sixtus IV one in the Vatican). Nearby is the family tomb of Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

That thing is purported to be the former Pope Pius V, the fellow whose preposterus bull Regnans in Excelsis in 1570 excommunicated England's Queen Elizabeth I, urging English Catholics to assassinate her, which did them no favors at all. Religious worship in England thereby became political and potentially criminal for a whole class of people; the Catholics' civil rights were restored there in 1829.

The many columns of the huge nave are said to be either original from the first basilica or scavenged from some other ancient Roman building.

A mini-aedicule with

A nice version of the Madonna and Christ Child in the same pose as the venerated 'Salus Populi Romani' (Salvation of the Roman People) image supposedly painted by the Apostle Luke and either brought to Rome by Constantine's mother St Helena or imported from Crete in the 6th century by Pope Gregory the Great -- but it's not the same one, which is in the Pauline Chapel nearby.

That self-important chap over against the wall of the front porch is the Spanish king Philip IV, a major benefactor of the basilica, possibly designed by Bernini.

A last look at that weighty entry porch

The fancy belltower, or campanile, is the tallest in Rome and dates from the 14th century.

Now we're going to look about for the churches of the two Roman sisters, Pudentiana and Praxedes, saints and martyrs of the mid-2nd century; they're in the neighborhood here somewhere.

The Birreria Marconi, we're on the right track; this is the Via di Santa Prassede (i.e., Praxedes).

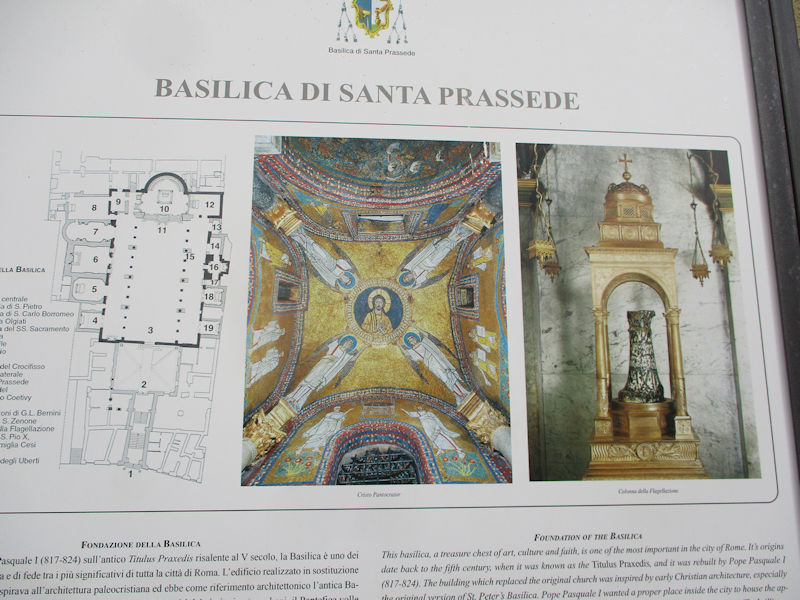

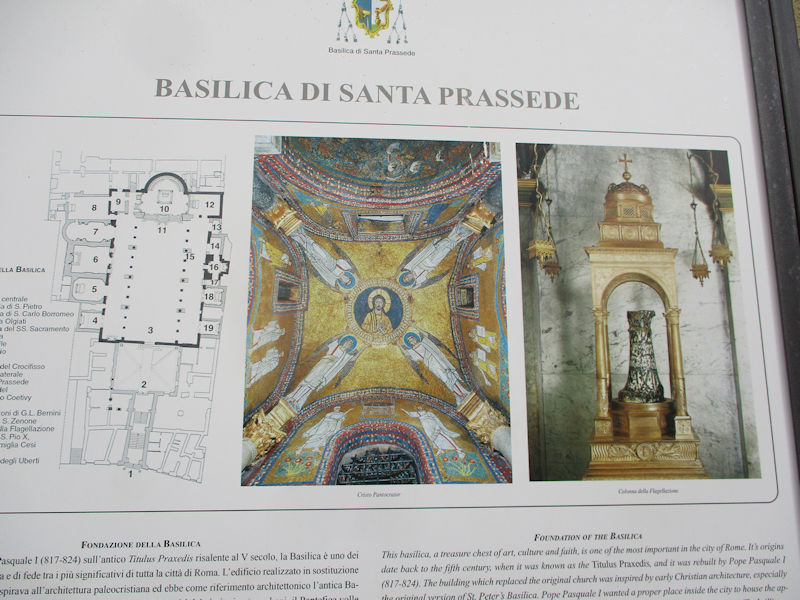

The mini-basilica, 'a treasure chest of art, culture, and faith', dates back to the 5th century, rebuilt in the early 9th. Major church names have been associated with it at some point in their careers, like Saints Cyril, Methodius, Charles Borromeo, and Robert Bellarmine.

It's very nice -- uplifting, calming, inspiring in some ways. Especially with the fine mosaics sprinkled all round.

The main altar

Love the floor. Inspiring; calming.

In the crypt; one of the good works the sisters were known for was helping 2nd century fugitive Christians and, in particular, burying them when required, and apparently the later planners of the two churches were interested in bringing some of the earlier Christians buried Roman-style outside the city walls back into community, so to speak.

Poor Prassede, like her sister, was officially unsainted by the Catholic church in 1969, but luckily their churches were left here.

[This is actually a misunderstanding. No saint can be 'unsainted' or 'decanonized', evidently, but in 1969 the Roman church revised the General Roman Calendar of feast days, etc., and removed something like 300 saints, identified in several complicated categories, from the list of universally recommended feast days. Any saints can still be venerated by anyone who feels like it or by any locality or religious order that prefers to stay in touch. Some in the 1969 loser list were referred to as 'removed', others as removed from particular calendars, but the recommendation for both St Pudentiana (19 May) and St Praxedes (21 July) is that they be venerated in their own 'Titular basilica only'. So the B Team, in effect. (added in Dec. 2024)]

Dwight Peck's personal website

Dwight Peck's personal website