|

Dwight

Peck's lengthy tales Dwight

Peck's lengthy tales

Castle-Come-Down faith

and doubt in the time of Queen Elizabeth I

Part

1. ENGLAND (1577-1583) CHAPTER

VII. SUMMER IDYLL (1580) "For

this be sure, the flower once plucked away,

Farewell the rest, thy happy days

decay."

-- Walter Raleigh Some

few held out hope. Captain du Bourg returned in March, de Vray joined him shortly

afterward; letters passed back and forth across the channel. M. Simier kept in

contact with his friends--but Mauvissière, the French ambassador, did not. When

Lord Harry called at the French house, he was engaged; when accosted in the galleries

at court, he was hurrying to the queen; when passed on the water in his boat,

he was busily reading or observing the flights of various birds. The matrimonial

ball had taken on a theme, which was the papist combination. The counsellors warned

of it, the townsmen grumbled at it, the preachers thundered it out like Boanerges--and

so perhaps, Mauvissière would now suggest, Monsieur was not really the papist

he had been thought to be; perhaps he was on the point of conversion to the pure

gospel; perhaps he needed but a nudge, or an inducement. Anjou himself wrote to

the earl of Leicester, solicitous of his health, grateful for his friendship,

assuring his friendship in the future when he as king-consort and the earl as

his prime minister should make this island a fortress of the pure faith. Leicester

passed these notes about like the latest corantos. From the French point of view,

the Catholic courtiers had become an embarrassment. At

first the gentlemen were puzzled. The queen still looked to be in love. She still

wrote lovingly to Simier, who assured them that one day all would be right again.

Sussex bid them keep heart and be patient, for one day another opportunity would

present itself and they should have Leicester over the hip at last. And

so, through the early months of 1580, they clung to their small hope. The strain

told upon them. Quarrels arose among them. Petty differences magnified to a monstrous

bigness brought occasionally the hotter blooded young men to blows. The Catholics

in the country were coming in for a new scrutiny. Many were detained, in jails

or bishops’ houses, for ecclesiastical retraining, and once again the prisons

were becoming the best places to go for Catholic companionship. In

late spring of 1580, a new Maid of Honor was preferred at court. Her name was

Anne Vavasour, the daughter of Henry Vavasour of Yorkshire. She found her place

through the agency of her kinsfolk, to whom she was entrusted, and her aunt Catherine

Paget in particular watched over her and introduced her to the ways of court life,

while Thomas Lord Paget, Catherine’s brother-in-law, and Catherine’s

brothers the Knyvets took a special interest in her welfare. Then Mistress Vavasour

caught my lord of Oxford’s eye. He was seen with her in the galleries. He

danced with her at the balls. Occasionally he wore her favor, and spoke dreamily

of her beauties as the gentlemen played at cards. Her friends began to fear for

her. Nan was a tall girl, fully

Oxford’s height, with a stern, forbidding face, long and sharp with an aquiline

nose and a tiny, bitter mouth. In other dress than the fineries she wore, she

might have made a good preacher’s wife, in appearance. Her attractions for

an amorous dilettante like Oxford were not obvious. Her friends in the Howard

clan admonished her of the perils of the earl’s attentions. Matters progressed,

and the flirtations became openly known at court. The

Lord Treasurer sent to Lord Harry and Mr. Arundell and earnestly asked their counsel.

They had no counsel for him. But something must be done, Burghley persisted, for

his daughter was becoming the laughingstock of the court, with her husband leering

after every drab in the palace. Lord Harry promised that they would try their

uttermost to restrain the venerous earl. That

evening they met in Oxford’s house in Bread Street. Mr. Cornwallis was there

as well, with Mr. Noel and Mr. Swift. After some talk passed of the meal and the

wine, the earl fell to inveighing against French perfidy, and insulted upon Monsieur

as the greatest villain in Europe at that time. History

stood as his witness, he said, that the French had a tradition of crowning none

but jackanapes and cockscombs, and had Monsieur ever come to marry the queen they

would all have lived to sorrow for that day, for he was but a faithless Frenchman

and therefore naught. Mr. Arundell objected that if Anjou himself were but a temporizer,

yet M. Simier, throughout his sojourn here, had been constant in his faith and

meaning. But Oxford would admit of no exceptions and denounced the race of Frenchmen

categorically. It was an empty conversation, listlessly pursued, for the matter

seemed devoid of interest after all these months. Too near the surface lay recriminations

for efforts untried, advantages unfollowed, words unsaid and deeds undone, all

the thousand reasons offered why success had not been theirs.

|

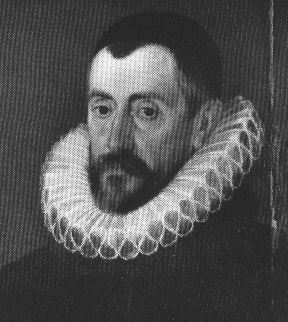

Lord

Harry Howard, ca.1594, later 1st earl of Northampton in the next reign |

When the other gentlemen

had left, Lord Howard sat in the window paging through a book of prophetic pictures

that Oxford had acquired in some obscure corner of the realm. Arundell was speaking

solemnly to Oxford, instructing him in the duties of clan, which precluded the

lascivious dalliance with young kinswomen newly come up from the country. The

earl grinned impudently. Arundell was growing angry, as he began listing off the

gentlemen who considered themselves her protectors, all of whom would take in

very ill part any alteration of her feminine state. Oxford hinted that he might

outface them all, and that in any case he was not the man to be threatened like

a boy by the Howards, who were already deeply suspected and were besides an ineffectual

brood whom he might please or displease as his fancy took him. Arundell

waved aside this fanfaronading and pressed on; he cited the Lord Treasurer’s

concern, but received from the earl only his accustomed ‘father-in-law’

speech of blustering obloquy. Finally Arundell endeavored to convince the earl

that he was making a laughingstock of himself as well. He spoke of a conversation

he had overheard, in which two gay companions had twitted the earl for his having

to descend to the cradle for his amorous triumphs, for his seeking out young virgins

fresh from the country to overawe with his old-fashioned sonnets and powder-blue

bonnets, whilst the real prizes of the court smirked behind their fans at his

apish gracelessness. Oxford began seeing red, his choler inflamed by a goodly

deal of sack. Arundell pursued

his advantage by describing Raleigh’s new poem, a witty courtly exercise

which had now been read by everyone but Oxford, the butt of its conceit. The earl,

who disliked Raleigh anyway, insisted upon hearing the verses. Charles called

down to Lord Harry, who was dozing by the window, and Harry withdrew from his

bosom a folded sheet of paper with Raleigh’s poem neatly written out upon

it. "Here it is, Ned;

let us see, let us see," Arundell said, unfolding the paper with a needless

flourish and peering closely at the lines. "‘Mr. Raleigh’s advice

to Mistress Nan,’ we read; a pleasant title, Ned, a pleasant beginning." And

he read aloud: Many

desire, but few or none deserve

To win the fort of thy most constant will.

Therefore take heed, let fancy never swerve

But unto him that will defend

thee still.

For this be sure, the fort of fame once won,

Farewell the

rest, thy happy days are done. "There

is more, Ned, can you bear to hear it?" smiled Charles unkindly. Oxford glowered

at him in a slow rage. Many

desire, but few or none deserve

To pluck the flowers and let the leaves to

fall.

Therefore take heed, let fancy never swerve,

But unto him that will

take leaves and all.

For this be sure, the flower once plucked away,

Farewell

the rest, thy happy days decay. "God’s

blood!" cried Oxford, snatching the paper to see for himself that so much

insolence could be written with pen. "I shall kill him! Not deserve! No man

more deserving. And having killed Raleigh, so much more desert!" "Who

means to kill Raleigh?" asked the somnolent Lord Harry. "If so, Ned,

haste were needful, for Raleigh departs for the Irish wars in less than a week’s

time." "There, you

see, Ned," said Arundell. "He’ll never meet your challenge now,

for he is on the queen’s service." Oxford’s

face worked in drunken thought. "Well, then, if I cannot kill him honorably,

I shall have him slaughtered." "But

look you, Ned, he expresses in these numbers what every man would tell her to

her face. You have not a friend so long as you persist in this. Will you slaughter

every decent man at court then?" Oxford

stood up and steadied himself. "I

will kill Mr. Raleigh--I will baggle that false maid in her lap--and I will kill

every man at court who says me nay. Especially the house of Howard!" And

he flew out of the room, shivering his shoulder as he lurched into the jamb of

the door. Arundell and Lord

Harry Howard poured themselves a bit more of the earl’s hospitality. Howard

wondered whether his friend had not proceeded too far with the man. Charles replied

that he feared he had done, and that Raleigh must be warned and cousin Vavasour

looked to more straitly. Lord

Harry said in jest that perhaps this book of painted pictures should tell them

what will come of it at the last. And with that, they departed.

|

Sir

Francis Walsingham, 1532?-1590,

Principal Secretary |

In June the news was all

of Jesuits. At court, the Principal Secretary, Sir Francis Walsingham, had learned

of their dispatch from Rome, and rumors floated everywhere that ten had landed

at Portsmouth; thirty had come ashore at Flamborough Head and escaped into the

countryside; fifty were awaiting the winds at Calais, and the ports were laid

for their coming over. Walsingham had captured some priests, but the assignment

of the Society of Jesus here was an escalation in the international war for hearts.

The Secretary, in his zeal, never doubted the Jesuits were coming in to counsel

the traitorous papists to insurrection--that they were in the van of the pope’s

army, which even now being expunged from Ireland would soon throw itself against

the homeland. The word was

rife among the Catholics, too, and reactions were divided. Many pious souls, having

heard that the renowned Campion was among those travelling hither, dreamed of

meeting that great man, who (when Protestant) had charmed the queen at Oxford

no less thoroughly than later he had charmed the pope at St. Peter’s, and

they planned ways to hear him preach if only once. Many lonely priests, harried

from house to barn throughout the realm and at nerves’ ends with the continuous

fear of arrest, the rack, and the gallows, looked to the Jesuits for encouragement

and renewal of their ebbing confidence. But on the other side were many papist

gentry, already hard pressed by searches and fines and sometimes arrests, who

feared that the Jesuits’ coming in would only excite the government to greater

severity against them. Occasionally they expressed the doubt that these professional

zealots, as it were, would come armed with large demands, requiring more sacrifice

of them than they were able to give. These men, strong as they could be in simple

faith, had oftentimes no taste for heroic deeds and martyrs’ deaths, for

they were ordinary men like their neighbors and kinsfolk; and though many resisted

the queen’s laws in the matter of conscience, they little desired to be called

in conscience to take up arms against her. In

the middle of June, the first Jesuit arrived, a man named Parsons, highly thought

of in Rome but little known in England. Coming over alone, disguised as a demobbed

captain from the wars in Flanders, he reached London at midnight and searched

all the next day for lodging. Suspicion of travellers ran high in the capital,

and no innkeeper would trust him for a room. So he entered the Marshalsea prison

in Southwark as a visitor, and through the Catholics interned there he made his

contacts with the papist gentry in the country. Another

Jesuit, "Mr. Edmunds" the jewel merchant, came over two weeks later.

He was the second and the last for some time; the thirty at Flamborough Head returned

to the smoke of fearful or overly hopeful brains. When the word went round that

Edmund Campion had come at last, excitement ran through the Catholics from family

to family across the land. A band of young gentlemen, organized by Parsons in

advance, met him and brought him up the river to London, where he was lodged secretly

in Mr. Gilbert’s house in Chancery Lane. The feast of Peter and Paul was

approaching, and everyone wished to hear him preach. The Catholic houses could

never accommodate the crowd that would be flocking to him; the Bear Garden on

the Bankside might never have held them all. Accordingly, Lord Paget hired a very

large house in Smithfield especially for the occasion, and there on the 29th of

June Father Campion preached his sermon. Trusted servingmen were posted round

the house, and during the assembly they met in the street nearby one Sledd, a

low man and an informer, whom they wrestled into an alley and held there till

everyone had safely departed. Sledd made his report, however, and though Campion

and everyone else went their ways unharmed, the investigations turned up Paget’s

name on the lease and he fetched up in the house of the Dean of Winchester, until

some fourteen weeks later he consented to go to the Protestant services. The

Jesuits met later with many of the gentlemen and older priests in Southwark, near

Lord Montague’s house in St. Mary Overies by the bridge. There they gave

assurances that they came with no political intentions and would thrust their

presence upon no family uninvited. This put many an uneasy heart at peace. But

at this meeting, Arundell and Lord Howard were not in attendance, for they had

ridden south for a meeting of their own, a holiday meeting in the country with

friends. At Northumberland’s house, Petworth in Sussex, they encountered

Francis Southwell, who had come down separately, Sir John Arundell of Lanherne,

Mr. William Shelley of nearby Michelgrove, his cousin Richard Shelley, and the

earl of Northumberland himself. Henry

Percy, the eighth earl, was eight or ten years older than Arundell, yet Arundell

still thought of him as a younger man. He was a great, bluff man, moody and excitable,

given to bursts of energy punctuating long periods of uneasy lassitude. Years

ago he had been a carefree soul, but his brother’s rebellion in 1569 and

execution a few years later had brought him up quite short. Since then, on best

behavior, he had gradually rejoined the country society in the south--he was forbidden

to reside in his ancestral territories in Northumberland--and to some extent he

had made his way at court. Eventually he was restored in blood to his brother’s

titles, but his great fear was that he was being kept in convenient storage for

a scapegoat at any future need. In

the evening, the talk gravitated towards issues of concern. The first matter was

the advent of the Jesuits, but there was little to be said of that; only time

would instruct them in the fathers’ intentions and the government’s

response. Someone asked Lord Harry to report on the queen of Scots’s affairs.

Her correspondence continued to be channelled by himself and others through the

French embassy, for conveyance abroad to her agents on the continent. What the

agents did there in their negotiations with the French king, with her cousin the

duke of Guise, with Philip II of Spain, her wellwisher, he could not say. Her

spirit continued hopeful; her friends among the English spoke constantly for her

greater liberty, so far to no avail. As

Lord Harry spoke, Northumberland’s man Pudsey came in to announce the arrival

of a latecomer, the earl’s new famulus Charles Paget. He sat with the rest

and listened impatiently, then interrupted to ask Lord Harry when Queen Mary would

be free at last. Lord Harry

was taken aback. "Only God knows such a thing at that, who shares his counsel

with no man," he replied. "Hannh!"

Paget snorted, with a sneer writhing across his thick features and a gleam of

some queer triumph shining in his eye. The

men stared at him in perplexity. Paget, ogling them one after another, bounced

on the edge of his chair like a man awaiting a signal to be off and running. "Nor

will she ever be free if she depends upon the Englishmen her good friends, as

they maintain." Richard

Shelley shifted uncomfortably on his bench. "And

so we are her friends. What would you have of us, my dear Paget?" he inquired,

to whom Paget was not dear at all. "This

only will I say," quoth Paget with great asseveration. "The queen my

lady is in durance and has been these twelve years or more, and one of these days

this cunning beast Leicester will contrive to chop off her head. Daily our friends

are similarly put in ward, and now it is his lordship my brother, tomorrow it

shall doubtless be ourselves. The Lord helps those who first help themselves--I

say no more." Northumberland

listened carefully, his rather dull eyes following Paget’s gestures, nodding

his head slowly as belatedly he recognized the man’s meaning. "Mr.

Paget, it is my experience that hasty and precipitous actions do ever come to

grief in the end, and unrestrained speeches find unwelcome hearers. Pray you,

guard your tongue." Lord Harry was speaking slowly, as if to prevent exciting

the man unnecessarily. "Aye,

milord, I know of your guarded tongues and your cautious circumspections, all

the whiles our lady pines in durance," said Paget. "Let us guard our

tongues for five years more, till not a man of us is free to speak her name among

friends, nor she alive to be spoken of." "What

would you have, Charles?" asked Northumberland. "There is no man here

who does not like you lament of this case, but we must learn to suffer what we

cannot learn to change, is that not so?" "I

do not agree," cried Paget. "Then

say your mind," said Arundell, staring at him intently. "Nay,

say your mind if you will," said William Shelley, "but it is for other

ears than mine to hear." He

rose and started for the door. "Stay,

stay," said the earl placatingly. "We are all friends here, Will, we

speak here to only walls and friends." "I

am sorry, my good fellows, but I have not that lion’s heart to speak of changes

and enlarging from durance and other matters fit for this time. I will leave you

to your confabulations and badinage now, and seek my bed in good season. With

all good will, gentlemen, I take my leave." Sir

John Arundell and the other Shelley similarly arose and made their farewells,

and rode off with Will to Michelgrove. The rump parliament then resumed its debates.

Paget’s solution to their present ills was simple: He, adventurous, would

lead a band of dedicated men to free the queen of Scots, Northumberland would

rally the Catholics in the south and then rendezvous on the coast with an army

sent out of France from her cousin, the duke of Guise. The duke had already been

in touch with certain special friends in England, he said, and his grace’s

willingness to undertake the enterprise was understood. The

idea of the duke of Guise’s invasion was not entirely a new one. The Spanish

ambassador Mendoza was said to have brought it up in selected company, in whispers.

Guise was nothing if not Catholic, Catholic enough to seem more Spanish than French,

and his alliance in this cause with Philip of Spain, if the terms should be advantageous

to him, was not a preposterous notion. Five

years ago Arundell would have found such boyish plans merely laughable. Things

had changed since then. The marriage talks had failed, the courtiers were far

worse off than before them. Now he was afraid. Afraid for Queen Mary, afraid for

Lord Paget, for all Catholics, for all old friends, for himself and Lord Harry,

exposed as it were upon a rocky head facing out to the winter sea, Leicester watching

his moment to engulf them, the French withdrawn and with them the cause which

had been their chief stay and only foundation; Sussex himself beleaguered, wary

of them, Burghley standing off high up the coast, murmurings in court of a mass

said or an unkind word of great councillors: one wave, one breaking wave from

the right quarter, striking upon just the proper angle, one wave only, would suffice.

Arundell would be swept from his desolate promontory, into boiling waters, reefs

and skerries, wards and keepers, oaths, charges and what proofs, a little true

and much more feigned, and finally, to what end? Constraint? A dagger? A gallows?

Where did Catholics end, when caught straggling friendless, beyond the help of

great protectors? Where did Leicester’s enemies end, when once the Bear fell

sedulously upon them with his claws that rend and tear? They end wherever he would

have them end. Paget droned

on, rehearsing again to Northumberland’s labored questioning the details

of his vapid, hysterical schemes. Arundell heard him only a little, and permitted

himself to dream foolishly of an heroic day of conquest, Leicester defeated and

led in gyves through Traitor’s Gate, Arundell astride a charger parading

in Cheapside, his gleaming helm drawing gasps from the women, his avenging sword

the admiration of all the men; eulogies read above Ludgate by solemn scholars,

in Latin, to the gallant captain who had led God’s hosts against the heretics,

who had with a handful of loyal English and the aid of some pious Frenchmen delivered

this realm from atheism, from Machiavellian policy, from Aretinical license, who

had liberated both the English queen from those base minds which ruled her and

the Scottish queen to become her cousin, and sister, and trusted heir, as she

always should have been. Captain Arundell, even as nets were spread to ensnare

him, traps were laid to catch him up, arises and smites the pagan champions, routs

the pagan hosts, saves his country on the brink of her ruin. Exsurgat Deus,

et dissipentur inimici eius! Let God rise up! Let Leicester take to his heels

or turn them up. The debates

were continuing without him. Lord Harry was demonstrating with unappreciated thoroughness

that the ancient fathers were unanimous in condemning insurrection against God’s

viceroys in the secular seat, while Paget was interrupting him by noting that

such good doctrine did never apply to heretics. Harry, citing Augustine, was proclaiming

the irrefragable conclusion of passive disobedience as the uttermost allowable,

but Northumberland, having lost him in this patristic fog some ten or twelve sic

probos earlier, was plainly rapt by this notion of action, this ill-thought

plan for action, this vague and thrasonical promise of action, this call for action,

some action, which Paget now posed against their waiting, as he phrased it, like

chickens for the blow of the axe. Paget’s plans were like Arundell’s

daydreams, full of glorious, gore-smeared entries into towns hard-won, with caps

thrown high for the liberators, the queen of England grateful and the queen of

Scots delivered, their oppressors chained neck to neck, marched in columns before

their chariots. And to this music Northumberland must dance; Lord Harry’s

donnish quiddities must give room to action, only action. Southwell

and Arundell felt some of this as well, and so, in fact, did Harry, whose dissuasions

arose from habits begun in gentler years. Then it had been the hotheads who listened

to such words of war, the fanatic or crazy man who uttered them. Now the hotheads

spoke, and sober gentlemen listened. Half in the spirit of the thing, Arundell

began to press this midlands Ajax with more pointed questions. He asked how the

Scottish queen could infallibly be ensured. In ‘69, the first measure taken

against the Northern Earls had been her prompt removal from their path. With no

mark left to shoot at, their bows had never been drawn. The earls had reversed

their headlong march and dispersed northwards, to their several fates, half into

exile, the other half to heaven or hell. How to prevent a recurrence of this peremptory

dealing? Timing was all, was

Paget’s reply, timing and communications. The Scottish queen is enlarged

and scurried into hiding--a small force, with surprise, will suffice--then post

is ridden to lather towards the coast, where the duke of Guise’s men and

the English forces watch their opportunity. The signal given, the duke lands at

Portsmouth, whence on to London. A two days’ war, ad majorem gloriam

Dei, and victory. "Well

enough," said Arundell, somewhat pensively. "But now this. Put case

the duke of Guise is now come to London, and all evildoers are shut away. What

is to be done if the duke himself will not retire?" "But

that is an impossibility," cried Paget. "His grace wishes but one issue

of this cause, to free his good cousin and all his Catholic brethren. Which accomplished,

he must needs by goodness and reason then retire to his home beyond the seas."

Lord Harry snorted at this

witless logic, and muttered that for his part he would rather suffer the kicks

of an English tyrant than the slaps of a French one, and such a French one who

could kick with any tyrant in Europe. He had no doubt that Paget’s play,

however it was written down before, when it came to the acting out, would end

with King Henry the Ninth, the duke of Guise in the present queen’s crown,

upon the battered throne of England. Paget

was suffused with wrath, and he spluttered. "That

he will not do; I pledge me, he will not!" he cried intemperately. "Why,

my lord, you must forgive me. Our Lady Mary is his very cousin, whom he has always

loved before himself. He will find her crown for her wherever this schismatical

whore may seek to hide it, and he will place it square upon her sacred head and

kneel before her!" The

others, save Northumberland who had missed his implication, were dumbfounded.

"This whore!" cried

Arundell. "Damn me, Paget, you say this whore?!" Paget

realized his admission and chose to face it through. "What

a God’s name is our travail to win?" Paget pleaded. "Our lady must

be freed, and she must have her crown, not in ten years, nor twenty, but even

now as right is." Arundell

growled and lashed out across the benches at him, striking him full in the face

with his main strength. Paget dragged him backward as he fell; the two men grappled

at one another’s throats across the boards, kicking out against the wainscots

and striving for the upper hand in fury. Southwell, closest to them, shouting

"Now, gentlemen!" leapt upon them and endeavored to stay their hands,

but Paget had his dagger out, waggling it at arm’s length as he sought an

opening for his thrust. Lord

Harry propelled the earl violently out of the way and trod upon Paget’s forearm.

The man screamed out an oath and flung his weapon from him, and Southwell, lying

across them both, smothered their attacks. Both men came only gradually to their

senses. Arundell arose and

adjusted his clothing. "She

must have her crown, indeed, but upon my life, she must wait her turn." Paget

glared at the floor. "These

are treasonous speeches, and I will have none of them," said Arundell. "We

will have no talk of new queens here." "You

draw your treasons very nicely, Charles," said Howard. "We must take

arms against the queen, but take no arms against her." "There

you are right! These are misted matters; the queen is our mistress with all obedience

after God." "In

matters lawful," said Southwell. "In

matters lawful," said Arundell. "To rise against the earl of Leicester

may be good or ill, I stand not upon terms in that question now; but to rise against

the earl for the queen’s own sake, and to have our Lady Mary declared successor

in despite of the earl and his minions, these are on the one side--to rise against

the queen herself is clean on the other, and I will hear no more of it." "Then

it is finished," said Lord Howard, "and we remain all friends."

And so, apologies said all

round, albeit grudgingly, the gentlemen retired to their beds, where, lying taut

in his like the bow lines of a galley in rough anchorage, Arundell dreamed fancifully

of overthrowing the Leicestrian Bear before those great bloody claws came down

upon them all.

In

the morning, rain fell and the sky was gray, and the gentlemen’s moods matched

the day. The others proposed to reside with the earl until the weather turned

more merciful, so Arundell took horse, said his farewells, and set off for London.

He found himself reluctant to be too long away from the court. In their absence,

anything might be said by malicious tongues; anything might be begun, traps set,

actions started, rumors invented and sent flying and taken universally for sober

truth before he had returned to scotch them. In the great circles, they had few

favorers to protect their interest in their place. Sussex continued their friend

and bade them continue his; the old earl was a good man, but still larger stakes

lay in the pot, and to him a gaggle of suspected Catholics must always be expendable. Who

else might help them at a need? The French had left them stranded. Burghley sympathized

with some of their hopes, but loved them little personally. Vice-Chamberlain Hatton

did them kindnesses, but Arundell, though he liked Hatton for his wit and many

parts, would trust him very little if push should ever unhappily come to shove.

Oxford they had little use

for; his tergiversating spirit would one day cause them woe. He had once been

in their bosom, but that only made him the more dangerous now, for his behavior

since those days had been a kind of blackmail, in which he presumed upon his acquaintance

with their secret faith, and ever stood, in the fullness of his pride, apart from

them even in their closest camaraderie. There

remained no one else worth reflecting upon. Many of the younger gentlemen had

grown away from them since the failure of the marriage plans. To live at court

was a kind of profession, which brought its own responsibilities, not least among

which was the duty to press one’s suits and seek after favor wherever it

could be had; the aspiring young men, like Walter Raleigh in fact, were not to

be blamed for finding their friends elsewhere, as many of them now began to do,

in places where suits planted might grow fruit. And, increasingly since the routing

of Monsieur, the blessings of patronage at court seemed all Leicester’s to

bestow. Of the gentlemen who

still looked to the Howards for their aid at court, one kind was predominant--the

Catholics. Not Arundell’s sort of Catholics, though, those who felt a little

better after a mass, who distrusted the intellectual chaos of these burgeoning

new sects; who simply felt a deep aversion, almost an aesthetic aversion, from

these hard-headed, loudmouthed professors of the new gospel; who loved the old

ways, the old hospitality, the old abbeys with their gorgeous vestments and their

devotional arts painstakingly pursued. Rather many of these were the new Catholics,

as zealous often for the pope as the wildest preacher was against him, a kind

of puritanical papists who embarrassed Arundell’s sensibilities almost as

much as the hot gospellers did. Would that men, he thought, would put aside these

interpretings and inquirings and return a little to simple fellowship and common

feeling, so that Englishmen might think and drink together with never a quarrel

of creeds. All this talk of

violent redresses would come to no happy end. Arundell knew that, and yet he was

tempted to think of them himself. To win England back to the faith were doubtless

a noble and a godly deed, but Arundell’s ambitions were nothing so high as

that. For him, it was his sense, in part only of a simpler age passing away, to

be hauled back (it sometimes seemed) by any means at all, but more than that,

his sense of impending doom, his shapeless sense that if he did not act now for

himself, others would act against him, to his ruin. But violent means, and desperate

talk of jars, were repugnant to his good nature, and he put such thoughts away

from him. He would cross no swords, conspire in no alleyways or dark corners ever,

murder no men, imprison none, bring no rabid Frenchmen in to win him any grace.

He would strive to keep himself out of harm’s way, and await a better day,

a better day which, he persevered in believing, must one day come. Just

past Epsom, Arundell came upon a party of farmers addressing themselves to the

road’s decay. They worked despite the misting drizzle that had continued

through the morning, and Charles wondered what threats some ferocious justice

of the peace must have uttered to bring about such display of industry. Otherwise

the track was deserted. The climate sufficed to keep folk in at doors. Thus deprived

of one of the few small pleasures of travelling, musing upon the travellers one

sometimes passed, Charles was grateful for the sight of a single rider behind

him, and slowed his pace in hope of company. But when he looked back again, the

rider was gone from view, and he resumed his way. Again,

before Sutton, another traveller was visible behind him, and again he relaxed

his pace, but once again, upon peering back through the mist, he found the man

had stopped or gone off another path and was nowhere to be seen. He rode on. Near

Mitcham, another rider behind, and Arundell halted and watched for his approach;

far off, dimly perceived through the fog and falling rain, the black-draped man

also halted, then turned about and receded towards the south again. A

chill came into Arundell’s bones. Three riders, or the same one? A vision

rose before him of a hideous, wicked little rodent’s face, with one nacreous

eye blind to the world of light, the other glowing supernaturally, peering everywhere,

watching him through walls, through doors, through rainy mists on the highroads

of Surrey, turning, following him, peering suspiciously, knowingly; accusing him,

threatening him, understanding every secret he held--two eyes, one blind to his

good, the other unnaturally alert to his sins, the spy, the informer, the demon

sent to carry him into hell. Soiled with his recent talk of treasons, again he

was being watched, or so, excitedly, he was convinced. Arundell

shuddered and tried to dismiss his nervous thoughts. He stirred his horse and

made on for London. But it had been him, the loathsome one-eyed footpad, he was

sure of it, his bad angel, this accursed thing sent out to haunt him even in his

sleep. Arundell’s mind worked feverishly. Here was your new age, he thought,

here was your godly reformation--one milked-over eye, blind to the good in men,

another peering everywhere in their secret souls.

Arundell

arrived at Greenwich Palace late in the evening. He paused atop Black Heath near

Greenwich Hill and stowed himself among the trees once more to await his following

nemesis. No one appeared, and after a time he continued down the slope towards

the Thames. Striding a little

later across the Privy Gardens, below the palace gatehouse, he came upon Tom Knyvet

sprinting furiously towards the stables. The fellow dashed out of the darkness

and nearly ran him down, but grabbed at his arm and tried to bear him along with

him. "My God, Charles,"

cried Knyvet. "We are too late. Come, man, run." Arundell

let himself be hurried into the stables he had just left. He saddled his second

horse himself. Knyvet explained in breathless fragments that word had just been

brought him: Oxford had been seen furtively departing upstream from the water

stairs, some time since, in company with a cloaked and shrouded lady. There

was, to be sure, a futile humor in the situation, and Arundell considered leaving

the earl to enjoy his venerous triumph, but Knyvet was spluttering with family

honor and not to be called off. Certainly a violent scandal would turn unwelcome

attention upon the entire clan. Together they clattered out of the stables and

rode at a full dash through the palace yard onto the highway, through Bermondsey

to the bridge. Up to the bridge they came at a gallop, the late passersby scattering

before them, beneath the Great Gate, under the shops and tenement dwellings that

arched above them overhanging the black race of water, past old St. Thomas chapel

at mid-stream, clattering three hundred meters to the northern bank. Into Gracious

Street on the other side they flung themselves, then westward up East Cheap and

Cannon Street in the direction of Paul’s. Approaching

Walbrook, Knyvet cut off towards London Stone, where one of Oxford’s houses

lay. Arundell, following Knyvet’s sign, bore on towards the other house,

in Bread Street, behind St. Paul’s School, where he rode in through the side

gate and dashed up into the hall. Rafe Hopton scurried over, looking quizzically

up at his master’s friend, but Arundell brushed him aside and started up

the great stairs. "Please,

sir," called the boy, "his lordship has retired." "When

I have done, Rafe, his lordship will have need of you." At

the top of the staircase, the earl’s man Curtis appeared like a sentry from

a tiny room on the left. "Pray

you, sir," said Curtis, putting his hands up to restrain the intruder. But

Arundell flung off the man’s arm and struck him in the chest, and Curtis

fell away groaning. Arundell

ran down the narrow corridor to Oxford’s room and burst through the door.

To his surprise, the chamber was empty. From

somewhere above, he heard a squeal of laughter, followed by the unmistakable sound

of a horse whinnying. "God’s

nails," Charles muttered. He ran along the hall towards the next stairs,

a sense of the ludicrousness of his task swelling up within him. The delighted

squeals and improbable equine bellowing continued as he ducked his head and raced

up the steps. Arundell reached the stairs’ head and threw open the door. Two

figures turned in surprise. Oxford, grinning foolishly, stood stark naked in the

middle of the chamber. His erection cavorted gaily before him, and he bore a curtains-cord

tied about his loins for reins. These were held behind him by Nan Vavasour, just

as naked but still in her bonnet and slippers, her breast heaving in excitement,

her eyes dancing and lit from within. They

stared at Arundell with broad grins across their drunken faces. Then Oxford whinnied

again, lurched forward, and resumed prancing in a circle round the chamber, Nan

following him, snapping the reins upon his arse and squealing again with pure

happiness, her pendulous breasts and buttocks jouncing and swaying with each high-spirited

step. They came full round

the room again and stopped before him. "My

dear Charles," said Oxford. "You’ve met my lady?" Arundell

stared at them. Here was Nan’s attraction, he thought, not in her pinched

look (deceptively stern, as it turned out) and her long Howard nose, but in these

big, saltatory breasts and the full, black patch between her thighs. Oxford seemed

rather to be pitied than condemned. "I

came to save you," Arundell said drily, "from my lord’s lecherous

intent." She snapped her

reins again upon the earl’s arse and murmured, "Thank you, cousin Charles." Charles

grinned back at them and said, a little sheepishly, "And now I must leave

you, friends. I am called away on the queen’s business." And

Oxford whinnied again as Arundell shut the door upon their sport and descended

the stairs. As he left the house, he found Curtis looking pallid and withdrawn,

and tipped him generously. Another

of life’s little jokes, thought Charles, as he rode home towards the Priory.

But life could be amusing, these little jests upon one’s heavy seriousness

sparkling up out of the general gloom. He found he thought more kindly of both

of them now than he had before. They could still laugh, at any rate. To be young

again, he thought. He would describe the scene, with appropriate neighs, to Kate

when he reached his rooms. They would laugh a little, too, and be young again,

if only for a little while.

Matters

for Catholics, already bad, steadily became worse, suspicions of them deepened,

as summer passed into autumn and the court returned to Whitehall. Rumors ran throughout

the realm of a Holy League compacted on the continent, of Guise and King Philip

and other Romish princes, for the reduction of England to the faith. Another papal

force had landed in Ireland, and their reinforcements were expected daily. Accordingly,

the government tightened its control upon the known English Catholics, and set

about ferreting from their nests all the unknown ones. The conforming gentlemen

were caught in an intensified dilemma, for just when official pressure to attend

the queen’s service was increasing, so were the Jesuits promulgating the

pope’s strict insistence upon their refusal. More rumors told of a Parliament

forthcoming, in which new woes would be enacted. From France, there came still

more bad news; Monsieur had been turned against Simier, had sworn him as an enemy,

and the Howards’ last friend in the Anjou camp could be of no more help to

them. Any progress Monsieur made in England now would only come at Leicester’s

hands. Oxford continued his

inhabiting of Anne; their liaison had become a secret de polichinelle

at court, but he was reckless, his courses became increasingly erratic; he grew

more and more a stranger to his erstwhile friends, and when he joined their company

as often as not it was to taunt them with rude and childish jests. At other times,

he grew lugubrious, and sentimentally sincere, and complained to Arundell in maudlin

tones of the happier years long lost, the shifting, treacherous sands upon which

now they stood. Usually, he avoided his former companions as if they were embarrassments

to him, or threats to him when Anne’s name came to mind, and they in turn

eschewed his company, for his unpredictability. In

autumn, Arundell went down to Bristol to tend to his affairs. He alone of all

the gentlemen preferred to stay by Oxford’s side, for whereas they thought

safest to be away from his sight, Arundell was possessed of other doubts. The

earl had always been unstable, to be feared for the damage he might do them in

any little fit of pique; but additionally he had always been ambitious, and Arundell,

wondering to see him so long in the shade, expected momently some new break from

Oxford, some headlong, ill-thought jump into what he feebly might conceive to

be glory or fame, or merely somewhat better odds. Like the others, Charles feared

Oxford’s violence against them; what he feared, however, was not the puerile,

aimless tantrums of which the man was sometimes capable, but the calculated betrayal,

in which art he was no less competent. It

was thus with many misgivings that Arundell rode out from court, for whilst he

was in the country on the queen’s business, his nightmares might be taking

shape at home.

| Go

back to the Preface and Table of Contents |  | Go

ahead to Chapter VIII. Leicester Triumphans (1581) |

Please

do not reproduce this text in any form for commercial purposes. Historical references

for events recreated in this story can be found in D. C. Peck, Leicester's

Commonwealth: The Copy of a Letter Written by a Master of Art of Cambridge (1584)

and Related Documents (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1985). Feedback and

suggestions are welcome, Please

do not reproduce this text in any form for commercial purposes. Historical references

for events recreated in this story can be found in D. C. Peck, Leicester's

Commonwealth: The Copy of a Letter Written by a Master of Art of Cambridge (1584)

and Related Documents (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1985). Feedback and

suggestions are welcome,  .

Written 1973-1989, posted on this site 10 June 2001. .

Written 1973-1989, posted on this site 10 June 2001.

|