|

Government Suppression of Elizabethan Catholic Books the case of Leicester's Commonwealth

D. C. Peck Copyright © 1977 by The University of Chicago

GOVERNMENT SUPPRESSION OF ELIZABETHAN CATHOLIC BOOKS: THE CASE OF LEICESTER’S COMMONWEALTH D. C. Peck Abstract: The Protestant government of Elizabethan England had at its command a large number of means to prevent the production and circulation of Catholic books. To meet the challenge posed by the scurrilous tract known as Leicester’s Commonwealth (1584), the officials employed all of those normal means and invented some extraordinary ones for the occasion. From the evidence of the book’s circulation and its later effects, however, the government’s attempts at suppression must be said largely to have failed. Perhaps at no time in history has the word "sedition" been so regularly and so frequently invoked as in the Elizabethan English government’s attempts to control the printed propaganda of its enemies. In document after document, in statute, proclamation, Privy Council warrant, and official correspondence the phrase "seditious books" appears sufficiently often to suggest that there was design in its use and that the government, having adopted the phrase, intended to see that it should become familiar. All Catholic books, whether political, controversial, or purely devotional, were "seditious" because they were divisive of the officially Protestant realm and because they encouraged allegiance to a foreign "head of state," the pope, who in 1570, by the bull Regnans in excelsis, had deposed the heretic queen and absolved her subjects from their obedience.1 The English government fully understood the power of the press in shaping public opinion, as it understood its own dependence upon the goodwill of its subjects. It made ample use of the press in its own behalf, not only in the publication of proclamations and statutes with their self-justifying preambles, but also in a constant flow of official and semiofficial news reports, controversial treatises, even ballads and public prayers [3, 4]. Consequently, after its harassment of Catholic laymen and its indefatigable persecution of priests, the suppression of papist propaganda was among the government’s chief activities in combating the old faith. The present study is an attempt to reconstruct, in the light of our general knowledge of Elizabethan methods, the case history of the government’s response to one book in order to observe those methods in operation, the steps taken to circumvent them, and to attempt to gauge their efficacy. Leicester’s Commonwealth is a particularly good example for this purpose, because both sides exerted themselves extraordinarily over it. The pamphlet, justly celebrated for its ferocious satire of the queen’s chief favorite, Robert Dudley (1533-88), the Earl of Leicester, became almost instantly a cause célèbre and inevitably evoked more emotion and activity than milder books. Nevertheless, one must bear in mind that the whole range of English Catholic printing remained, despite the government’s vigilance, a formidable weapon in the Counter-Reformation arsenal, for, as the expatriate, former Secretary Sir Francis Englefield, wrote to a friend: "In stede therfore of the sword, which we cannot obtayne, we must fight with paper and pennes, which can not be taken from us"[5]. In the first decade of the reign, the Louvainist doctors believed that by skillful controversial argument (and the undoubted weight of truth) England might be recovered to the ancient faith by books alone [6, p. 30]. Dr. William Allen, himself an able controversialist, also understood that if the religion were to remain alive in England at all purely devotional works must be provided for the edification of the surviving faithful. Robert Parsons, S.J., the most vigorous Catholic political writer of the age, "also wrote what was incomparably the most popular book of spiritual guidance in sixteenth century England" [7, p. 205]. And, of course, the political agitators of the Roman side understood the value of propaganda in weakening the opposition. In the plans for the abortive "Lennox Plot," for example, it appears that the Catholics "have most infamous and sclaunderous libels ready made, but not yet printed, which then [upon invasion] shall be published with other proclamations; to which end they appoynte to have a printer with them."2 Similarly, Allen’s Admonition to the Nobility, which called upon English Catholics "to adventure your selves in a quarell most honorable" by rising up to support the Spanish liberators, was intended to accompany the Armada’s forces into the realm.3 Some general remarks on the problem may be ventured by way of background before we turn to the Commonwealth. First, it should be noted that the output of Catholic printing was quite high. In the course of the reign, from 1558 to 1603, some 260 different books in English which are still extant appeared from papist presses, most of them printed on the Continent but many on the "wagonback" presses operating surreptitiously in England. Of this total, some 62.6 percent date from the latter half of the reign, indicating the same general growth that occurred in the industry as a whole.4 The Catholic presses were prolific and much feared, and the government employed a number of means to suppress them. Largely by means of its licensing system it undertook to drive papist printing out of the legitimate book trade. Regular licensing of books "for expellinge and avoydinge the occasion of errours and seditiouse opinions" was set up in Henry VIII’s proclamation of 1538, but it was irregularly enforced [11, p.48]. A more thorough apparatus was established in the charter of the new Stationers’ Company in 1557 and in Elizabeth’s injunctions to the guild two years later. In these it is laid down that virtually all new works must be seen and allowed either by privy councillors or by highly placed ecclesiastical officials. Moreover, the company was granted a categorical "search and seizure" warrant which permitted its officers to destroy any works printed contrary to regulations. The company was only too glad to make use of its powers, for, while enforcing the government’s political aims, it simultaneously was able to protect its own monopolies and copyrights. So the master printers carried out most of the routine control of the trade, and according to some authorities they seem to have taken over the routine tasks of licensing as well [10, p.60]. The Star Chamber decree of 1586 tightened things up still further, and thereafter all works claiming legitimacy had to be previewed by agents of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of London. The papist writers were thus denied virtually all access to the regular publishing industry.5 So they printed clandestinely, both at home and abroad, and to this activity as well the government responded with vigor. Customs officials had authority to examine all cargoes, and searchers were employed in all the great ports to watch for printed contraband. The havens and creeks were left to the local pursuivants, who also conducted from time to time and with apparent relish house searches of known recusants. Arrests for smuggling occurred frequently enough.6 But compared with the amount of importation which seems to have been going on, they seem to have been quite few. This relative lack of success must be blamed on papist ingenuity and the technological inefficiencies of government in those times, certainly not on any want of trying. The best shaft in the Privy Council’s quiver, however, was to strike the fear of both God and the queen into the moderate Catholics who were a potential audience for such books and into their inquisitive Protestant neighbors as well, for the latter, if they saw a "seditious book" and failed to report it, might find themselves jailed at the queen’s pleasure. Various acts of Parliament strictly prohibited certain limited kinds of propaganda, in most cases Puritan as much as Catholic attacks upon the queen. In 1 Elizabeth, cap. V, iv (1559), anyone affirming in print that the queen was not the lawful sovereign was guilty of high treason [13, p.24]; 5 Elizabeth, cap. I, i (1563) provided that anyone holding for the pope’s jurisdiction in print was guilty of praemunire [13, p 39].7 Issued the year after the Bull of Excommunication, 13 Elizabeth, cap. I, i (1571) made treasonous any writing or printing which called the queen a heretic or usurper, and article v, the famous "statute of silence," prescribed a year’s prison for anyone who named in print any person as heir to the throne except her own "natural issue" [13, pp. 60-62]. Also, 23 Elizabeth, cap. II, iv (1581) proscribed any book which contained slanderous matter against the queen herself or encouraged active rebellion [13, p. 78]. One notices in reading them how impeccably legal are these laws. They provide sensible penalties and ample due process. In prohibiting "seditious books" they aim at books which are genuinely seditious – those which attack the legitimacy of the queen’s authority or actually incite to revolution. The prerogative laws, the proclamations which had not had the status of genuine statutes since 1547 but which continued to be treated as if they had, were less scrupulous of semantics. The proclamation of March 1, 1569 prohibited any "matter derogatory to the sovereign state of her majesty," but then included any matter "impugning the orders and rites established by law for Christian religion and divine service within this realm, or otherwise stirring and nourishing matter tending to sedition" [14, no.561]. Defending the efficacy of the mass was now sedition, and one read such a defense "upon pain of her majesty’s grievous indignation." The proclamation of July 1, 1570, against circulating seditious books and bulls [14, no.577], went still further, establishing elaborate rules for turning over to the authorities any copies one might have stumbled across, chiefly so as to ensure total secrecy. It offered rewards to informers. Anyone actually naming an author "shall be so largely rewarded as during his or their lives they shall have just cause to think themselves well used." Guilty parties naming authors earned both reward and pardon. Other proclamations of 1570, 1573, 1584, and 1588 [14, nos. 580, 598, 672, 699] also spoke out against all kinds of Catholic books and their distributors, some amplifying directives or stiffening penalties, others merely ordering that such books be thought badly of by the true subject. There were other proclamations against other books as well, but those mentioned here were aimed specifically at the Catholic printers and readers and were often occasioned by specific Catholic books. In general, the entire legislative and police apparatus for the suppression of seditious books must be said to have done its work fairly well. Ample evidence exists of distributors and readers jailed, whole consignments confiscated, treatises failing of an audience for want of the ability to print them. Printing in England was especially perilous, and not much of it was tried, but William Carter’s press did turn out 11 titles before its owner, who had been arrested first in 1579 and again in 1581, was executed for treason in early 1584 [6, pp. 351-52; 15, pp. 20-22].8 The well-known peregrinations of Parsons’s Greenstreet House Press, which rival the story of the Puritan Waldegrave’s Marprelate Press for sheer romance, ended only after some 8 books had been dispersed. And there were several other presses, like Verstegan’s in Smithfield, which saw their 1 or 2 titles into print then promptly, and discreetly, disappeared. But the government’s rigor had its effect, and the Catholic writers who tried working in England lamented constantly the one-sided unfairness of the controversial struggle. Robert Parsons justified his delay in replying to an attack by the government hack, William Charke, by complaining thus:

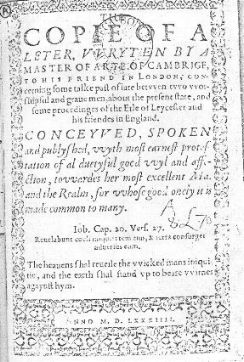

The troubled Jesuit does not mention that not only did he lose his press and book in this raid on Stonor Park, Henley (August 8, 1581), he also lost his pressman Stephen Brinkley and four assistants to the Tower of London [6, p. 356]. Presumably as a consequence of the perils attached to printing within the realm, most Catholic books were produced in the various centers of English refugees on the Continent. There still remained, however, the problem of transporting the materials into England. At first this was done more or less haphazardly, but after Parsons’s retirement to France in 1581 he began the development of an increasingly sophisticated network of routes and contacts for the importation of priests, books, and holy apparatus, usually to obscure ports in the north country or the Sussex coast and thence to London. In this rather loose "system" for infiltration, a singular method of distribution was contrived to evade detection: "all the books are brought together to London without any being issued, and after being distributed into the hands of the priests in parcels of a hundred or fifty, are issued at exactly the same time to all parts of the kingdom." Care was taken to see that many copies were left in the homes of irreproachable Protestants, too, "into workshops as well as palaces," in order that Papists might not stand condemned for possession alone.9 Clearly, though the officials made their road a hard one, what ingenuity could supply the Catholics had in abundance. It was in this manner that Leicester’s Commonwealth first appeared before the world, though anonymously and under its proper title [17]. It quickly acquired the name "Leicester’s Commonwealth" in contemporary gossip, and this became the title given on the title pages of its reprintings in 1641.10 The pamphlet was written, probably in Paris, in late spring 1584, though it seems to have incorporated materials brought out of England some months earlier. It was printed, probably in Rouen, during that summer.11 Its authors, principally Charles Arundell but several others as well, were not priests but Catholic ex-courtiers some of whom, bested in factional intrigues at court, had been hounded into exile by the Earl of Leicester in the preceding autumn [19, pp. 100-101]. Their book is a final desperate attempt to present the views of the conservative old nobility who had been all but finally superseded in power by the "new men" and their Puritan allies. In the tract, they argue eloquently for religious toleration of all faiths, and they restate the claims to the throne of their patroness Mary, Queen of Scots. Most readers, however, then and now, have missed these more sober remarks because they lie buried amid a shocking mass of invective against the Earl of Leicester himself, who is presented as a murderous aspirer who had brought England to the edge of ruin in his unrestrained quest for absolute power. Well-known facts, persistent rumors, and bold lies were woven skillfully by the authors into nets of circumstantial evidence which convict the earl of murders, adulteries, hypocrisy, manifold abuses of patronage, and sinister conspiracies against the queen. Historical anecdotes are served up liberally to link him, for example, with Brutus and Catiline for treachery, with Sardanapalus and Heliogabalus for insatiable lust, with Attalus, Piers Gaveston, and the Spensers for wicked sycophancy, and with Nero and Phalaris for tyranny. Leicester had many enemies who charged him with many crimes. Many of the charges seem to have been at least partially true. But he was still a privy councillor who, for better or worse, enjoyed the favor of the queen, and so, even though the Commonwealth speaks of Elizabeth, Lord Burghley, and Secretary Walsingham in the most solicitous and kindly terms the government treated the book as an attack, not upon Leicester the man, but upon the entire regime and upon the queen from whom Leicester drew his power. Hints of the pamphlet’s existence first appear in August 1584. On the twenty-fourth of that month Sir Edward Stafford, the English ambassador in Paris, reported rumors of newly printed libels having been carried into England, "200 in a companie, to land some of them Westward, some by the long Seas."12 Some days earlier, Fr. Parsons had sent word from Paris to his superiors that his man Ralph Emerson had just opened two new routes into England and had smuggled in four priests and 810 books. Among these various shipments may well have been copies of the Commonwealth.13 On his next trip, however, Emerson was certainly bearing a consignment of Commonwealths. In London he somehow aroused the suspicion of the host of the inn where he was staying and found himself and his books attached.14 He was committed to the prison called the Poultry Street Counter, after interrogation, on September 26, 1584 [22, p.249].15 Immediately recognizing the potential for scandal which the Commonwealth presented, the government set about trying to determine its provenance. Lord Mayor Sir Edward Osborne sent a copy to Secretary Walsingham, who in turn read it and then, on the twenty-ninth, forwarded it to Leicester himself with a few shrewd guesses as to its authorship and the assurance that he had had the other copies sealed up close [23].16 Leicester was enraged. He sent Richard Hakluyt, Stafford’s embassy chaplain, back to Paris in early October with a demand that the ambassador find out where and by whom it had been published [19, p. 95]. Stafford was really on better terms with the exiles (his kinsmen) than with Leicester and Walsingham, and there is some reason to think he may have had something to do with the Commonwealth’s production himself. Nonetheless, he duly made his inquiries among the exiles and reported back on October 29 that it had probably been printed in England, certainly not in Paris or Rouen! He recommended the matter be left alone [25]. Walsingham had confiscated one consignment but apparently other copies had got through, for in the meantime, a proclamation had had to be issued from Hampton Court, against seditious books in general but occasioned principally by the Commonwealth [14, no. 672]. In it, the queen denounced its abominable lies in general terms and required all copies to be surrendered to privy councillors if within twenty miles of the court (or to the custos of each shire if further off), offering amnesty to all persons who immediately surrendered their copies. Those possessing copies who did not come forward were to face indefinite imprisonment. But the proclamation was not enough. On December 16 a bill against "scandalous libelling," also occasioned chiefly by the tract, received a second reading in the house of Lords and was sent into committee. It seems never to have emerged from committee, however, perhaps because the provisions of 13 Elizabeth, cap. I (1571) against discussing the succession to the crown were considered adequate to the Commonwealth’s transgressions [26, p. 317]. On March 17 following, a similar bill was read to the Commons and rejected, probably because the Puritan members feared it could be turned against themselves [26, pp. 368-69; 27, pp. 94-95]. But the book continued to circulate. In April 1585, for example, a copy found its way to William Shelley, a state prisoner in the Tower, and back out again without detection [28, p. 76]. As time passed, the furor did not pass away, and the government tried other means to suppress the tract. Pressure was brought upon King James of Scotland, and on February 16, 1585 there issued from Holyrood House a proclamation against this book so "full of Ignomineis and reprochfull calumpnies" and vindicating "the honour and reputacion of our ryt trusty and ryt welbelovit cousing the erle of Leycester" [29]. Later, an even more extraordinary move was tried: in June 1585 the Privy Council sent out circular letters to the officials in several (and probably all) counties. In these letters, the council alludes to the proclamations already made but complains that despite them the very same "shamefull and devilish Bookes and Libells have bin continually spreadd abroad." It goes on to deplore the Commonwealth’s charges against Leicester, "of which most malicious and wicked imputacions her Majesty in her own clear knowledge doth declare and testify his Innocence to all the World" [30].17 It is significant that, as in the case of the Marprelate attacks, the government felt obliged not only to suppress the Commonwealth’s slanders but to deny them as best it could as well. Sometime during the winter of 1584-85, Sir Philip Sidney undertook to defend his uncle’s reputation. In his "Defense of Leicester" [34, pp. 129-41], which was evidently intended for publication but did not in fact find print, Sidney ignores the calumnies on the earl’s morals and concentrates instead upon refuting what had been only a secondary line of attack, the charge that Leicester was newly risen from base lineage – a reaction perhaps forgivable in a very proud young man whose lineage on his mother’s side was identical with Leicester’s own. He ends by challenging the unknown libeler to meet him in a duel within three months’ time. It is difficult to guess whether Sidney wrote upon request, as he did when a few years earlier he obliged the Leicestrian party with a treatise dissuading the queen from marriage [35, p. 108]. In any case his "Defense" was not published, probably because the government was at that time wary of opening up a public disputation on the subject of Leicester’s morals.18 Similarly during that winter, still another complication developed. In March 1585 Stafford reported to his superior the appearance of a French translation of the Commonwealth, one which included "a verye villienous addition" of new matter. In his dispatch the ambassador recommended that it be ignored, "for to compline of ytt were to have the matter more to be divulged abroade," especially since, as his "nearest have a touche in ytt" (that is, since it mentions Stafford’s wife, the former Douglass Sheffield), he might be suspected of personal motives should he make official representations to the French court. His greatest fear, however, seems to have been that he would be blamed for it, or at least associated with it in Leicester’s wrath: "Yf you commande me I wille send you [one] of them, for else I wille nott, for I kanne nott tell howe ytt wille be taken." At the end of his report, it appears that he had known something about it for some time, something which so far as we can tell he had not reported before: "I have kept ytt from the beginning that the other [the Commonwealth] camme out from translatinge heere, for Throgmorton19 was even then in hand with ytt, and by meanes thatt I founde left ytt off, and ever sence ytt hathe slept, and is butt nowe of a sudden gushed owte" [37]. This French edition [38] is an extremely close and accurate translation of the Commonwealth, pretty certainly an attempt by the same group of men to give Leicester’s notoriety a continental coverage. Its chief "villainous addition," a very amusing 20-page essay at the end, is aimed more explicitly at a French audience and expends considerable energy upon charges against the earl (such as his subversion of the Duke of Anjou in the Low Countries) which might particularly offend the French reader. More important, there are signs that this addition was considered by its author to be the second installment of a continuing campaign against the earl. He mentions, for example, further translations into Latin and Italian shortly to appear (but which, so far as is known, never did), and promises that other men (to quote a contemporary retranslation into English) shall "adde from day to day such his accions as the tyme shall discover . . . as soon as they can receave more large advertisement from England, from whence thear ys allredy gathered, as I hear, a good quantytye that shalbee augmented from more to more" [39, p. 203]. There is other evidence as well that a continuing campaign had been intended. The Commonwealth itself had spoken confidently of an anticipated second edition with more current material [17, p.58], and in Sir Francis Englefield’s letter of March 1586 that gentleman had wondered at several omissions in the Commonwealth’s charges and suggested several new allegations to be included in subsequent ventures [5]. Despite his hopes, however, the French translation was the second and last production of the exiled courtier group. Meanwhile, interrogations were being made of all state prisoners who might have had any knowledge of the book or its authors. Sylvan Scory, the Bishop of Hereford’s scapegrace son, was examined on February 12, 1585. He "never sawe the book" but "hath hard talk of the said libell . . . comenly at tables" [40, art. 1]. George Errington was examined on August 30, 1585, about a man who had been intercepted at Scarborough bearing copies of the Commonwealth [41]. Hugh Davies gave evidence on September 6, 1586, about a Robert Atkins, who had extolled the book’s virtues to him at offensive length [42, art. 5]. William Wigges, on June 22, 1587, professed to believe the Commonwealth "worthy to be burned" [43, arts. 1, 12, 13). In early 1586 Ambassador Stafford’s own man, one Lilly, was detained in London and examined for complicity. The ambassador defended him by explaining, erroneously, that merely to read such a book was no crime and by insisting that Lilly was being harassed because of Leicester’s malice toward himself [44]. Robert Poley, the same "poolie" whom the Commonwealth calls one of Leicester’s henchmen [17, pp. 96-97], was also interrogated for possessing a copy [45]. In addition to these measures, spies were instructed to root out the book’s authors and distributors. In April 1585 Thomas Rogers (alias Nicholas Berden) learned that 1,000 copies of the tract were being stored by George Flinton, the Rouen printer [28, pp. 72-73]. Later in the year, having infiltrated the exile community in Rouen, he reported that copies of the French translation were being kept in Charles Arundell’s lodgings in Paris [46]. In May 1585, the French ambassador in London wrote home that Leicester was still on the hunt for its perpetrators [28, p. 112], and on June 1, Mendoza, the Spanish ambassador formerly in London, then in Paris, reported that Stafford had been ordered to bring pressure upon the authorities there [47, p. 538]. In fact, Stafford was instructed to do this on several occasions, but he kept insisting there was nothing he could do since as a government representative he could not act for a private citizen, and he maintained that in any case he could never expect cooperation in such a matter from the French officials.20 But Stafford did his best, or so he claimed. He burned some 33 copies as they came into his hands [44] and may have gone further. Mary, Queen of Scots at least believed that Thomas Morgan’s imprisonment in the Bastille in March 1585 had been procured at Leicester’s instance, because the earl had come to the opinion that Morgan was one of its authors.21 We have seen the English government employing a large number of devices in its attempt to suppress this inflammatory treatise. Port searchers seized the colporteurs and confiscated their burdens; the queen issued a monitory proclamation to the public at large; the council applied further pressure in its circular letters to local officials throughout the realm; the government interrogated prisoners and unleashed its undercover agents in search of the authors, and attempted to gain aid in its censorship efforts in the courts of the Scottish and French monarchs. It even tried getting new parliamentary legislation enacted, though in this instance the attempt was given over. It was probably behind Sidney’s literary reply as well. Many members of the council hated Leicester fully as much as the Commonwealth’s authors did, but in cases like this the government closed ranks and acted as one. Leicester himself may have gone even further. In January 1585 it was reported in Paris that he had sent a man over to assassinate Charles Arundell, and two months earlier Thomas Morgan had been advised to go into hiding because the earl would punish him similarly for his supposed participation.22 But this is probably expatriate paranoia, and in any event it adds nothing to our understanding of the regular methods which the government had at its command. In all of these somewhat hysterical efforts to suppress the offensive book, the government must have been successful in some measure, as the relative scarcity of extant printed copies suggests. But in another sense its program was signally a failure. Leicester’s Commonwealth, ignored for its political arguments and received as a chronique scandaleuse, had become notorious and thus avidly sought, so that, even if the numbers of its printed copies were much reduced, it found its readership. At least one Puritan reader, vehemently unsympathetic to the book’s message, was sufficiently undeterred by the official threats to procure a copy and fill its margins with refutations and abuse.23 When printed copies were scarce, the few that survived were made to serve as copytexts for manuscripts which were circulated freely and recopied again and again. More than 65 of these are still extant. Some of them show the work of several hands from the same family, as if the copying had been done as a family enterprise, whereas others, owned by gentlemen or by such noblemen as the Earl of Stamford, show the hands of professional scribes, whose employment must have involved some expense.24 Extracts of its more vivid passages were sometimes copied out and passed about like the dictes of the philosophers.25 It was read so openly at court that the Earl of Ormond teased Sir John Harington by greeting him in the Earl of Leicester’s presence with, "Good morrow, Mr. Reader." When asked by Leicester what he read, Harington blushed and ("God forgive me for lieng") answered, "They were certaine Cantoes of Ariost" [52, p.44]. As late as December 1619 the Lady Anne Clifford was having the book read aloud to her by one of her servants [53, p.111]. There are still other signs that the treatise was widely read. Quotations from the Commonwealth, allusions to it, and the influence of its theoretical arguments and its portraiture of the earl fill the literature of subsequent years. A number of other libels drew heavily upon it for their matter. The manuscript tract known as the "Leter of Estate" of about 1585 borrows so liberally from the Commonwealth that, despite its antiquated and rather inept style, it was once thought to have been a rough draft [54, 55]. The Flores Calvinistici, a tiny Latin pamphlet by Julius Briegerus, was published in the Netherlands in two editions in February or March 1586. Over one-third of it comprises anecdotes from the Commonwealth aimed at discrediting the Protestant military cause in those countries, then being led by Leicester. A curious 20-page prose tract of about 1590, which elsewhere I have called "News from Heaven and Hell," largely by deft manipulation of Commonwealth material comically portrays the earl’s vain attempts to enter Heaven and his subsequent reception in Hell [56]. Thomas Rogers’s long poem of about 1605, a rhyme-royal tragedy after the manner of The Mirror for Magistrates, is almost entirely a versified paraphrase of the Commonwealth [57, 58], and many of the short poetical squibs written against the earl are likewise indebted to the tract [for example, 59]. A list of the important contemporaries who can be shown to have read the book would include William Camden, Sir Robert Naunton, Robert Parsons and William Allen, Harington, [Thomas Nashe], Thomas Wilson, the playwrights John Webster and Ben Jonson, and the author of The Yorkshire Tragedy. The Commonwealth’s image of Leicester himself has persisted, through the antiquarians of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, almost unqualified until the present era. However many and varied were the means the government had at its disposal for the suppression of unwelcome books, in this instance at least they appear to have been insufficient. Doubtless, by confiscation of copies and by harassment of carriers and readers, officials reduced its readership, but they were unable to control circulation of the tract entirely. Given the vicious and hyperbolic nature of its libel, it would be inappropriate to remark here upon the power of the truth to overcome suppression. Perhaps we can conclude, so far as this case instructs us, that when the public wants badly enough to read a book all government can hope to do is to make reading it inconvenient. REFERENCES 1. Meyer, A. O. England and the Catholic Church under Queen Elizabeth. Translated by J. R. McKee. London, 1914; reprint ed., New York: Barnes & Noble, 1967. 2. Clancy, Thomas H., S.J. Papist Pamphleteers: The Allen-Persons Party and the Political Thought of the Counter-Reformation in England, 1572-1615. Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1964. 3. Read, Conyers. "William Cecil and Elizabethan Public Relations." In Elizabethan Government and Society, edited by S. T. Bindoff, J. Hurstfield, and C. H. Williams. London: Athlone Press, 1961. 4. Jenkins, Gladys. "Ways and Means of Elizabethan Propaganda." History, n.s. 26 (1941): 105-14. 5. London. Public Record Office. State Papers, 53/15/552. Sir Francis Englefield to a correspondent, March 9,1586. 6. Southern, A. C. Elizabethan Recusant Prose, 1559-1582. London: Sands, 1950. 7. White, Helen C. Tudor Books of Saints and Martyrs. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1963. 8. Knox, T. F., ed. Letters and Memorials of William Cardinal Allen. London: D. Nutt, 1882. 9. Allison, A. F., and Rogers, D. M., comps. A Catalogue of Catholic Books in English Printed Abroad or Secretly in England, 1558-1640. Bognor Regis: Arundel Press, 1956; reprinted., London: W. Dawson, 1968. 10. Bennett, H. S. English Books and Readers, 1558-1603. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965. 11. Siebert, Frederick S. Freedom of the Press in England, 1476-1776. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1952. 12. Parsons, Robert, S.J. A Defence of the Censure. STC 19401. Rouen, 1582. 13. Prothero, G. W., ed. Select Statutes and Other Constitutional Documents. 4th ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913. 14. Hughes, Paul L., and Larkin, James F., eds. Tudor Royal Proclamations. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1964. 15. Rostenberg, Leona. The Minority Press and the English Crown, 1558-1625. Nieuwkoop: B. de Graaf, 1971. 16. Hicks, Leo, S.J. Letters and Memorials of Father Robert Persons, S.J. Publications of the Catholic Record Society, vol.39. London, 1942. 17. The Copy of a Letter Written by a Master of Art of Cambridge. STC 19399. Rouen (?), 1584. 18. Wing, Donald, comp. Short-Title Catalogue . . . 1641-1700. 3 vols. New York: Columbia University Press, 1948. 19. Hicks, Leo, S.J. "The Growth of a Myth: Father Robert Persons, S.J., and Leicester’s Commonwealth." Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review 46 (Spring 1957): 91-105. 20. Murdin, William, ed. Collection of State Papers. London, 1759. 21. Parsons, Robert, S.J. "Notes Concerning the English Mission." In Publications of the Catholic Record Society, vol. 4. London, 1907. 22. "Official Lists of Catholic Prisoners, 1581-1602." In Publications of the Catholic Record Society, vol. 2. London, 1905. 23. London. British Library. Cotton MSS., Titus B. VII, fols. l0-l0v. Walsingham to Leicester, Barn Elms, September 29, 1584. 24. Hotson, Leslie. "Who Wrote ‘Leicester’s Commonwealth’?" Listener 43 (1950): 481-83, and exchanges with Leo Hicks, S.J., pp. 567, 659, 745. 25. London. Public Record Office. State Papers, 78/12/105. Stafford to Walsingham, Paris, October 29,1584. 26. D’Ewes, Simonds. Journals of all the Parliaments. London, 1682. 27. Neale, Sir John E. Elizabeth I and her Parliaments, 1584-1601. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1958. 28. Pollen, J. H., S.J., and MacMahon, William, S.J., eds. Ven. Philip Howard, Earl of Arundel. Publications of the Catholic Record Society, vol.21. London, 1919. 29. London. British Library. Additional MSS. 31,897, fol. 9. 30. London. Public Record Office. State Papers, 12/179/44 and 45. Endorsed by Lord Burghley, "A copy of a lettre wrytten by Hir Majesty’s commandment to the Mayre of London, in defence of the Erle of Leicester." 31. Peck, Francis. Desiderata Curiosa, vol.1, pt. 4. London, 1732. 32. London. Stationery Office. Historical Manuscripts Commission, 13th Report, App. part 4. Hereford MSS. 33. Kempe, A. J., ed. The Loseley MSS. London, 1836. 34. Sidney, Philip. Miscellaneous Prose of Sir Philip Sidney. Edited by Katherine Duncan-Jones and Jan van Dorsten. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973. 35. Pears, S. A., ed. The Correspondence of Sir Philip Sidney and Hubert Languet. London, 1845. 36. Boyd, W. K., ed. Calendar of State Papers: Scotland, 1574-1581. London: Stationery Office, 1907. 37. London. Public Record Office. State Papers, 78/13/86. Stafford to Walsingham, Paris, March 30,1585. 38. Discours de Ia vie abominable . . . le my Lorde of Lecestre. 1585. British Library 10806.a.10. 39. Oxford University. Exeter College MSS. 166. 40. London. Public Record Office. State Papers, 12/176/53. Examinations of Sylvan Scory. 41. London. Public Record Office. State Papers, 12/181/78. Examinations of George Errington. 42. London. Public Record Office. State Papers, 12/193/18. Examinations of Hugh Davies. 43. Washington, D.C. Folger Library. MS. K.b.l. Examinations of William Wigges. 44. London. Public Record Office. State Papers, 78/15/15. Stafford to Walsingham, Paris, January 20, 1586. 45. London. Public Record Office. State Papers, 78/17/26. Robert Poley to Leicester, early 1585. 46. London. Public Record Office. State Papers, 15/29/39. Rogers/Berden to Walsingham, Rouen, August 11, 1585. 47. Hume, M. A. S., ed. Calendar of State Papers: Spanish, 1580-1586. London: Stationery Office, 1896. 48. London. Stationery Office. Historical Manuscripts Commission, 12th Report, App. part 4. Rutland MSS., vol.1. 49. Petti, A. G., ed. Letters and Despatches of Richard Verstegan. Publications of the Catholic Record Society, vol.52. London, 1961. 50. Labanoff, Alexandre, ed. Letters of Mary Stuart. Translated by W. Turnbull. London, 1845. 51. Boyd, W. K., ed. Calendar of State Papers: Scotland, 1584-1585. London: Stationery Office, 1913. 52. Harington, John. A Tract on the Succession to the Crown (A.D. 1602). Edited by Clements R. Markham. London: Roxburghe Club, 1880. 53. Clifford, Anne, Countess of Pembroke. The Diary of the Lady Anne Clifford. Edited by Victoria Sackville-West. London: W. Heinemann, 1923. 54. London. Public Record Office. State Papers, 15/28/113, fols. 369-388v. "A Leter of Estate." 55. Peck, D. C. "An Alleged Early Draft of ‘Leicester’s Commonwealth.’" Notes and Queries, n.s. 22 (July 1975): 295-96. 56. London. British Library. Sloane MSS. 1926, fols. 35-43v. Printed in Peck, D. C. "‘News from Heaven and Hell’: A Defamatory Narrative of the Earl of Leicester." English Literary Renaissance, in press. 57. Rogers, Thomas. Leicester’s Ghost. Edited by Franklin B. Williams, Jr. Renaissance English Text Society, vol. 4. Chicago: Newberry Library and University of Chicago Press, 1972. 58. Williams, Franklin B., Jr. "Leicester’s Ghost." Harvard Studies and Notes 18 (1935): 271-85. 59. Peck, D. C. "Another Version of the Leicester Epitaphium." Notes and Queries, n.s. 23 (May-June 1976): 227-28. 1. The meaning and effect of the Bull of Excommunication are best discussed in [1, pp. 135-38] and [2, pp. 46-48]. 2. From government abstracts of papers captured on William Creighton, S.J., September 4, 1584 [8, p. 428]. 3. Short Title Catalogue (hereafter cited as STC) 368 (1588). Nearly all copies were destroyed when the Armada failed to make its landing. 4. These figures are by my count from the chronological index in [9, pp.176-77]. Southern’s count of 206 [6, p. 31] omitted titles subsequently discovered, while H. S. Bennett’s figure of 250 [10, p.75] results from a slightly different use of the index. The new STC will doubtless turn up still more. 5. The frustrations occasioned by this want of a license sometimes compelled the Catholic authors to beg. In one preface, Fr. Parsons called upon his opponent William Charke to "procure us but a litle passage for our bookes: at leastwyse you [M. Charke] shall doe an honorable acte, to obtayne licence of free passage for this booke, untill it be answered by you" [12, p.11]. 6. See, for example, [6, pp. 35-36]. 7. Praemunire was the offense "of prosecuting in a foreign court a suit cognizable by the law of England, and later, of asserting or maintaining papal jurisdiction in England, thus denying the ecclesiastical supremacy of the sovereign" (Oxford English Dictionary). 8. Rostenberg misdates Carter’s execution as January 11, 1583 instead of 1583/84. Carter was the only Catholic printer executed in the reign, though two distributors (one a priest) were hanged in 1585 [11, p.88]. 9. Parsons to Fr. Agazzari, England, August 1581 [16, p. 85]. 10. The 1641 reprintings are entries L968 and L969 in [18]. 11. STC’s conjectural "Antwerp" is demonstrably mistaken, as that city lay in Protestant hands until its fall to Parma after a twelve-month siege in August 1585. 12. Stafford to Sir Francis Walsingham, Paris, August 24, 1584 [20, pp. 418-19]. 13. Parsons to Agazzari, Paris, 10/20 August 1584 [16, p. 227]. 14. From an account left by Fr. Weston [21, pp. 157-59]. 15. He was released after the queen’s death in 1603 and died at St. Omer’s in 1604. 16. For debate over the value of this letter as evidence of authorship, see [24]. 17. Virtually identical copies: to the officials of Lancashire and Cheshire [31, p. 45], to the Council in the Marches [32, p. 332], to the Justices of Surrey [33, p. 492], all dated June 20, 1585. 18. When in 1573 the publication of the Treatise of Treasons (STC 7601) so deeply offended Lord Burghley, he drafted notes for a rebuttal [36, pp. 554-61], but eventually followed Archbishop Parker’s advice, that "some things are better put up in silence, than much stirred in" (Parker to Burghley, Canterbury, September 11, 1573 [20, p.259]). In this and other cases, though there was no settled policy the officials chose rather to offer categorical denials in the queen’s name than to attempt detailed self-exculpations. 19. Thomas, one of the Paris exiles responsible for the Commonwealth and brother of Francis (executed July 10, 1584) of the "Throgmorton Plot." 20. On other occasions, however, for example when Verstegan’s libel (with copperplate illustrations) against Elizabeth’s persecution of Catholics appeared in late 1583 or early 1584, the ambassador found no difficulty in having the books suppressed and both author and printer jailed. On this occasion, of course, Stafford was able to speak officially for the queen as head of his government. (Henry Constable to the Earl of Rutland, Paris, January 16,1584 [48, p. 158]; see [49, p. xxxix].) 21. Mary to the Archbishop of Glasgow, Chartley, May 18,1586 [50, p. 362]. There is ample evidence, however, that the Earl of Derby, acting officially, arranged Morgan’s arrest for his alleged complicity in the "Parry Plot" (see, for example, Morgan to Queen Mary, Paris, March 30, 1585 [51, p.603]). 22. Morgan to Queen Mary, Paris, January 15, 1585 [20, pp. 456-57]; Hieronimo Martelli [vere Henri Samerie, S.J.] to Morgan, November 1584 [51, p. 421]. 23. Consult the copy in Marsh’s Library, St. Patrick’s, Dublin. 24. The arms of Henry Grey, first Earl of Stamford, are stamped on the contemporary copy, Folger MSS. G.b.11. 25. For example, British Library, Hargrave MSS. 168, fols. 395-403, and the "Earl of Derby’s Historical Collections," Sloane MSS. 874, fols. 7-12v.

|

The 16th Century reprints Other stuff

|

Dwight

Peck's reprint series

Dwight

Peck's reprint series Please

do not reproduce this text in any form for commercial purposes. Further historical

references can be found in D. C. Peck, Leicester's Commonwealth: The Copy

of a Letter Written by a Master of Art of Cambridge (1584) and Related Documents

(Athens: Ohio University Press, 1985). Feedback and suggestions are welcome,

Please

do not reproduce this text in any form for commercial purposes. Further historical

references can be found in D. C. Peck, Leicester's Commonwealth: The Copy

of a Letter Written by a Master of Art of Cambridge (1584) and Related Documents

(Athens: Ohio University Press, 1985). Feedback and suggestions are welcome,