|

Dwight Peck's personal website Dwight Peck's personal website

Sicily in December 2012

On the track of the Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Normans, French, Spanish, Italians and Commissario Montalbano

You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

Mozia and Selinunte

Sightseeing on the west coast of Sicily

We stopped in to visit Trapani and got stressfully lost, and couldn't get out of it, and went round and round, in tears of frustration, then slipped out the back way and ended up in a wedding party at the docks for Mozia.

Once out of Trapani, going south but avoiding the S115 provincial road, following instead the P21 "Salt Road", the views are semi-crap until you get past the Vincenzo Florio airport, and then you're in business. Inside the barrier islands called the Isole di Stagnone, here's the little ferry port at Salina Infersa north of the city of Marsala that gets you out to the island of Mozia.

Here's our little ferry, the cost is negligible and it's ten minutes out to Mozia.

The ferry runs out a channel through the ancient salt pans, the Saline di Trapani -- those oblong lumps are covered piles of sea salt harvested from these evaporation pools along the coast.

As we leave the coast, a glance back up at Erice about 20km to the north

Our pilot, skipper of the Jessica, promises to return for us at a time prefixed.

Mozia or Mostya (or Motia), or perhaps Mothia (or Motya), was one of the most important Phoenician (late 8th century B.C.) and then Carthaginian trading posts, with salt production in the lagoon one of its commercial priorities. The old city (which crowded into the entire island) was destroyed by the Syracusans in 397 B.C. (apparently the first use of a catapult in siege warfare), and in the Middle Ages the island hosted a monastery called San Pantaleo.

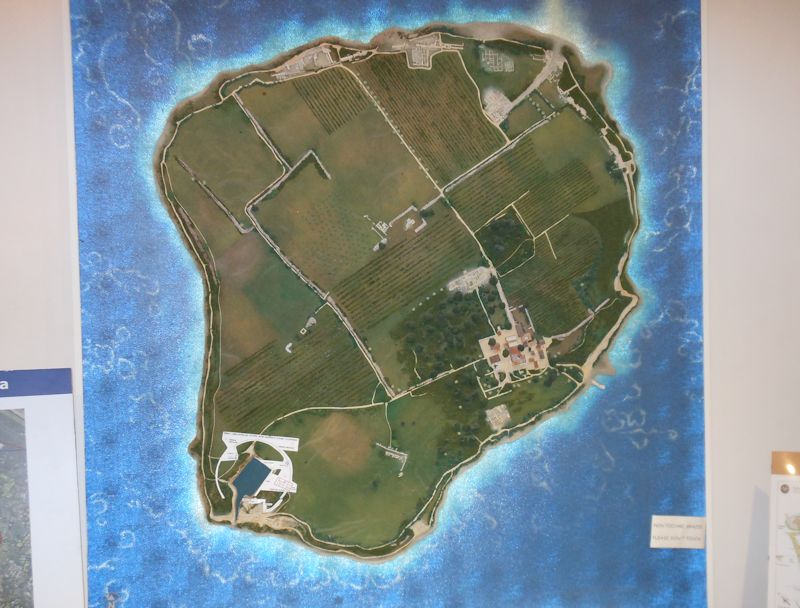

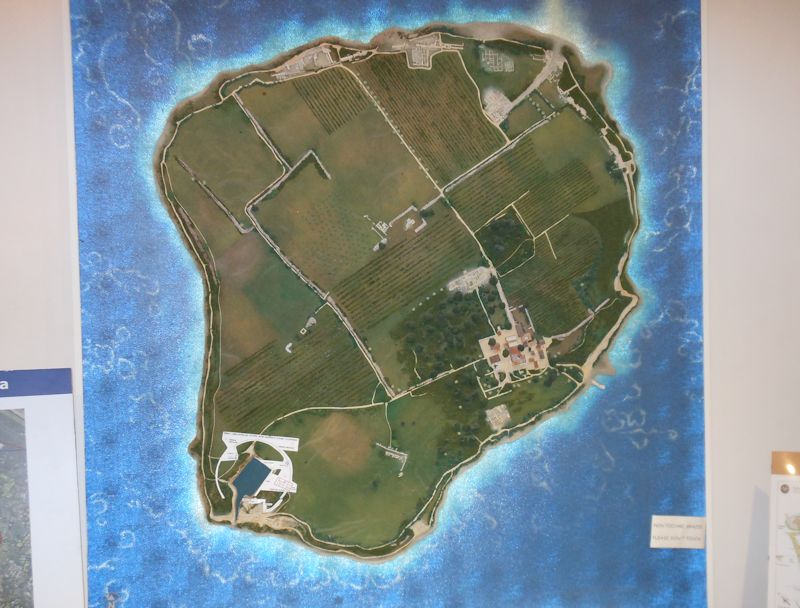

In the 1880s Joseph Whitaker, a rich birdwatcher who had inherited the Marsala wines concessions in the region and augmented his vast fortune by marketing them cleverly, bought the island, discovered archaeological treasures, and set up a Foundation that runs it to this day. It's considered to be the best-preserved Phoenician site extant. The Whitaker museum and landing stage are on the lower right, whilst the excavations at the old South Port are on the lower left, and the original North Gate and its causeway to the coast can be seen on the upper right.

The Whitaker Museum, well-presented artefacts

Rams fitted onto the front of Mediterranean warships, the triremes -- the principal methods of classical naval warfare were 1) to grapple alongside and invade overland, so to speak, with soldiers glad to be let out of the below-decks even for ten minutes, or 2) to maneuver your trireme cleverly and use your iron ram in the front to mash a big hole in your opponent's chances of getting out of this alive. Roman rams have been found around the Mediterranean, but the one in the foreground is described here as the only Carthaginian ram discovered so far -- not that the differences leap out at you.

You can't go here.

Kristin in the ruins. After the Syracusans annihilated the Motya population in 397, the Carthaginians reappeared immediately and the Greeks departed hastily, but the Carthaginians decided to rebuild at nearby Lilybaeum on the coast, the modern Marsala, instead. When the Romans annexed the area after the first Punic War's 'Battle of the Aegates Islands' in 241 BC, it was Lilybaeum that piqued their strategic interest, as Mozia was a flattened ruin.

The North Gate of the old city -- the main access to Mostya was along a causeway poking out from the more distant coast to the north.

Monte Erice across the lagoon -- not far beneath the surface here is the ancient causeway, the "Punic Road", that linked Mozia to the coast, now with rising seas about 1 metre deep.

The causeway was in use until the 1970s.

Ruins along the north coast of Mozia, temples and what not (with whispers of Carthaginian baby sacrifices, shhh). And a line of artisans' and tradesmens' shops.

The South Port

The channel into the South Port. We're scrambling now to meet our ferry pilot at the Whitaker landing.

Back to the mainland. The windmills are being restored and the ancient salt pans put back into production, both to supply the burgeoning gourmet salt trade and to cultivate a ecotourist interest as well.

One of the mills, presumably to control the flow of water through the evaporation pans and grind the harvested salt

As we continue southward along the Via del Sale or Salt Road, here's one of the many salt piles in the foreground and the evaporation ponds spread out along the coast. Gourmet sea salt produced by ancient methods is a promising niche market, and quite a few of these places (38 so far) on the Mediterrean and French Atlantic coasts are listed as Ramsar Wetlands of International Importance, because of their values for migratory waterbirds but also because of their cultural heritage.

We spent a few days in 2001 as guests of the Tour du Valat Biological Station in the Camargue in southern France learning how the managers move the water in and out of the various salt pans and harvest the salt. The Camargue and the famous Marais salants de Guérande et du Més, both in France, are only two of the artisanal salt works that are Ramsar Sites.

Marsala

Marsala, home of specialized fortified Marsala wines popular internationally since the late 18th century (but not for me), was built on the ruins of the Carthaginian city of Lilibeo, founded after the Syracusans torched Mozia in 397 B.C., and it remained a plaything of passing raiders through the Roman, Vandal, Byzantine Greek, Norman, Angevin French, and Aragonese eras. There's a story that the city's prosperity went into a steep decline after the Emperor Charles V ordered the main harbor filled in to prevent Saracen pirate raids in the 16th century. Good move.

The church is dedicated to St Thomas of Canterbury but is boring anyway. The city, now the 5th largest in Sicily, regained its former stature when in 1773 a passing Englishman named Woodhouse figured out a way of jiggering the local wines to make them easily and reliably transportable (like United Fruit's monoculture bananas), and put Marsala back on the map. English bombers took it off the map again on 11 May 1943.

This is where Garibaldi landed in 1860, so that's good, but we didn't find anything very interesting and went home for dinner in Erice.

Selinunte

Next day's got the Erice Fog on it, but we're far from deterred.

In fact, we're confident that if we can find our way to the car, we'll leave the fog behind us.

We've been out the autostrada past Segesta to pick up the southern highway to Mazara, passed by Castelvetrano and come down to the coast to visit ancient Selinunte. You'll recall that the Elymian Segestans had long-term issues with the Greek colonists of Selinunte, border skirmishes off and on from a few hundred years, and at the end of the 5th century B.C. the Segestans invited the Carthaginians to come along and lend them a hand. We're here to see what's left.

That's an impressive part of what's left, the so-called "Temple E", re-erected from the debris in 1958 -- there are three enormous temples here on a sacred hill across the little valley from the city's acropolis.

Temple E

Ditto

The other two temples (F and G) of the farther hill await their Resurrector.

All the Lego blocks are here waiting, all we need is a crane for a few weeks.

The ground plan of all three temples are discernible and are larger than other great surviving temples, like those at Agrigento, Segesta, and Paestum.

More sacred tinker-toys.

Kristin and former glories

Back along the other side of the hill, Temple E again

A side-on view. Now we proceed back through the entrance and carpark, where some sort of labor issues were in progress, but we eventually found our way over to the city itself on the next hill.

We're approaching the acropolis of Selinunte, and that's a look back at the hill of temples across the old river valley.

And a look down the coast at the modern, unedifying village of Marinella di Selinunte

Selinunte was the farthest west of the Greek colonies in Sicily and abutted irritatingly up against the Carthaginian interests on their side of the island, as this is nearly the closest port of call to Tunis/Carthage to the southwest.

Kristin and "Temple C", from the mid-6th century B.C. When in 409 the Segestans invited the Carthaginian powerhouse to come on over and destroy their rivals in Selinunte, Gen. Hannibal Mago obliged (not that Hannibal; all Carthaginian worthies for centuries seem to have been named Hannibal, Hamilcar, or Hanno), parked his fleet at Motia, and marched down the coast with overwhelming numbers. Allied cities, like Agrigento, Gela, and Syracuse, failed to show up in time to assist, and after a ten days' siege Selinunte became an ex-city.

Some 16,000 citizens were butchered, the rest enslaved, and the walls were knocked down. The survivors were allowed to return and rebuild under Carthaginian supervision, and during the First Punic War they were tormented by Roman and Carthaginian armies marching back and forth, but as the Carthaginians withdrew from the area in about 250 B.C., they leveled the city and transported the population to their stronghold at Lilybaeum up the coast. And that was that. Strabo the geographer, at the turn of the millennium, refers to Selinunte as one of the extinct cities.

-- It looks like this whole mess is being held up just by that little chock-stone.

-- What happens if we can just pull that out of there . . .?

-- Easily bendable trees in Selinunte

Pre-Columbian Chac Mool

The city was basically abandoned and forgotten -- a medieval earthquake knocked the big temples over as well -- until a 16th century monk figured out where it must be and found it; excavations got under way early in the 19th century.

The city walls round the acropolis -- it's a bit of a puzzle, evidently, because the circuit of these walls seems inadequate to contain a city of such importance. It's assumed that there was another circuit of walls, still unattested, encompassing the extensive suburbs to the north.

The northern fortifications, blocking the acropolis off from the northern suburbs on the hill of Manuzza

A staging area for troops to mass behind the front wall and, when the whistle sounded, dash out in a coordinated crowd and overwhelm their hapless foes

Kristin considering the long passage of time, and dinner

Looking down the High Street towards the sea, from the northern gate

The northern fortifications (and Kristin)

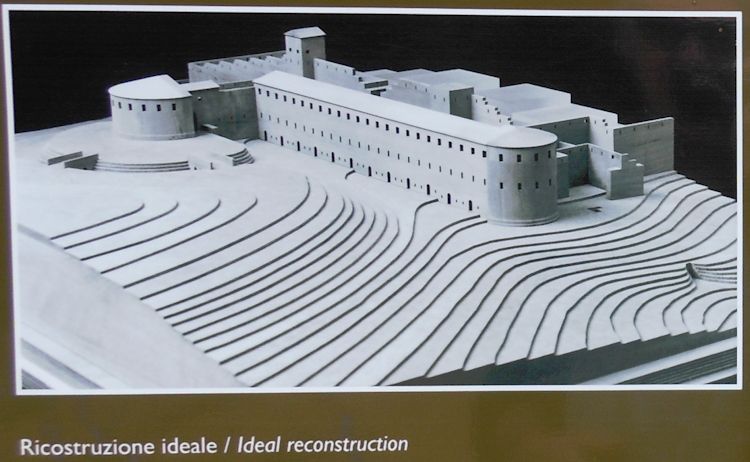

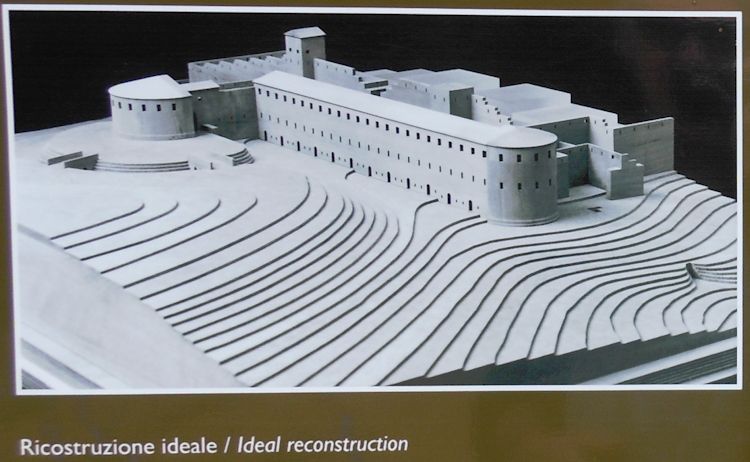

We're meant to understand that the original edifice looked something like this . . .

Now back along the eastern walls towards "Temple C"

And a long road home

Mazara del Vallo

Mazara was a Phoenician town from the 9th century B.C., the citizens of which we hope were able to carry on their trades and hobbies throughout their domination by Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, Ostrogoths, Byzantine Greeks, then after 827 the Arabs and after 1072, the Normans. And then, Frederick II's Swabians, and then the Angevin French, followed shortly thereafter by the Aragonese Spaniards, then briefly by the Savoyards and the Habsburg Austrians in the early 18th century. Then the Bourbons. Garibaldi and his Thousand took over in 1860 in the name of Italy.

Waffles with Nutella on. Waffles with ice cream on. Waffles with Nutella AND ice cream on!

Mazara is a important fishing port these days, currently caught up in the unfortunate tuna wars, and it's known as one of the most popular ports of call for North African immigrants, both legal and illegal. Evidently, though, the city fathers do as compassionate job as may be hoped for, to the extent of providing a school taught in Arabic and French by Tunisian staff for the kids.

That's the "Norman Castle" at the end of the piazza -- built in 1073 and knocked down in 1880 -- basically a sort-of-Norman-looking window.

Il Commissario Montalbano brought Livia here to Mazara on holiday, and the problems of illegal immigrants brought in by coyote thugs, and the selfless people helping to care for them, appear in Rounding the Mark (translator Stephen Sartarelli's title).

We're hunting for the Crazy Boy -- the famous "Dancing Satyr" found in the sea in 1998 and promoted to his own museum.

The nice policeman gave us very clear directions, but it's not here.

We're in the Piazza della Repubblica . . . looking for dancing satyrs.

The Piazza della Repubblica

There he is! The half-hour film with English subtitles tells the story of the fishermen's discovery of the ecstatic whirling-dervish-style satyr boy found half a kilometre down in the Med. Amazing!

Like everyone else, the Dancing Satyr looks better in the film than in real life, of course.

A Christmas market setting up outside the Dancing Satyr museum

Kristin checking out a nearby church

She evidently doesn't recommend it.

Ah.

A work in progress

A Dotto Train Muson River 1894, Euro 5, flashing past us before I could get my stupid new Nikon Coolpix S6200 warmed up. A very colorful one.

A convivial superstore (stocking up on Sicilian groceries for the trip home) off the crowded and very slow S115 highway north. (The west coast of Sicily is spectacularly underserved by coastal highways.)

We're back to Erice now and VERY ready for dinner.

And back to the San Rocco, grinning with anticipation, where last night's dinner was wonderful, and tonight's was nearly inedible.

Feedback

and suggestions are welcome if positive, resented if negative, Feedback

and suggestions are welcome if positive, resented if negative,  .

All rights reserved, all wrongs avenged. Posted 3 February 2013. .

All rights reserved, all wrongs avenged. Posted 3 February 2013.

|

Dwight Peck's personal website

Dwight Peck's personal website