You may not find this terribly rewarding unless you're included here, so this is a good time for casual and random browsers to turn back before they get too caught up in the sweep and majesty of the proceedings and can't let go.

We've just walked out of the Chiesa di Gesù Nuovo onto the Piazza of the same name, and we're about to visit the 'Complesso Monumentale di Santa Chiara' across the street. First, though, here's a vintage photo of the Chiesa di Santa Clara and its unattached belltower, taken in 2010 with a zoom lens from the Castel di Sant'Elmo up on the hill. That's the Majolica Cloister sticking out the back of the church on the right.

That's a tourist information office facing onto the square. The complex was originally built by Robert the Wise, the third Angevin King of Naples (r. 1309-1343), and his second wife Sancha of Majorca, carried out from 1313 to 1340. It was created as a 'double monastery', i.e., including males and females in separated facilities, and embodied the huge church itself, the monastery and its cloisters, and tombs of various worthies including Robert himself and the 19th century last Bourbon king, Francis II. There is presently an archaeological museum as part of it. The separate belltower was begun in 1328 but not completed for many years.

Closing time is preparing to loom over us, however, and we may have to choose between the church interior and the majolica cloister, and for better or worst we're opting to start with the cloister . . .

. . . just round the side here. The complex was built in the Angevin Gothic style ('Gotico Angioiano'), with some Romanesque vestiges that we didn't notice, but Baroque alterations were made in the 17th century by Domenico Antonio Vaccaro, he who also contributed the majolica makeover of the largest cloister with colorful early-Rococo tiles in 1742.

Following the disastrous American bombing of the church in 1943, however, restorations of the incredible damage were meant to bring it back to its original state, which were apparently somewhat controversial at the time; it was completed in 1953.

Into the Chiostro Maiolicato, frescoed round the walls and separated into four park-like yards bounded by hundreds of colorful rustic 18th century tiles that are fascinating in themselves.

We'll just take a hasty wobble round the pathways and memorialize some of the most representative of the tiles. Majolica tiles are twice-fired tin glaze pottery; these were hand-painted by Donato and Giuseppe Massa and installed here by Vaccaro in his 1742 transformations.

From that time to the 20th century, the Order of the Poor Clares lived their cloistered life of seclusion here and the tiles were never seen by outsiders. In 1925, the Franciscan monks here, who made no such seclusion vows, traded accommodations and cloisters with the nuns, and all this could be opened to the public.

It's been pointed out that these colorful scenes of a fanciful secular world outside the strict monastic confines seems incongruous with the holy contemplations of earnest monks and nuns. There may be no such arrangement in any other monastery anywhere.

Some of the scenes do seem to evoke semi-realistic versions of the local territory, but . . .

. . . others are wholly fanciful.

Festive secular life, with music, dancing, and ladies with wine-jugs upturned. (-- Eat your hearts out, brothers and sisters. Line up now, it's time for vespers.)

Perhaps those photos are enough to convey a sense of what's on offer here, truly worth more time than we can give them now.

Our party awaits us. The walls, as can be seen, are much frescoed, but most of it is fairly degraded by time.

Our team, Cathy, Oscar, Kristin, and an obtrusive passerby.

A bridge to nowhere

Into the museum for the very sad story: Between 1940 and 1943 there were about 200 bombing raids on the port and city, at first by British bombers through to 1942, mostly targeted at the port and ships, factories in the industrial zone and other infrastructure. In 1942, however, the Allies shifted to carpet bombing the city itself 'to demoralize the city and inspire revolt . . . [by] causing many civilian deaths' (Wikipedia). When the US bombers joined in in late 1942, they conducted daylight raids nearly every day, about 181 of them through to May 1943, targeting houses, churches, hospitals, office, the main Post Office, and often strafing the city before leaving.

The largest US raid took place on 4 August 1943, by 400 B-17 Flying Fortresses, and they gave this church a good shellacking. Over the whole Allied effort, 'estimates of civilian casualties vary between 20,000 and 25,000 killed'.

The armistice between Italy and the US and UK was signed on 3 September 1943 and was announced on the 8th, and the US ceased bombing some hours later. The retreating German forces took up the baton, however, and began their own raids on the city, the largest of which took place in March 1944.

Wow.

And somehow the Italians got all the mess cleaned up and the facilities functional again by 1953.

We're passing the 18th century presepe or nativity crèche on our way out -- the church itself will have to wait for another venture; we're back on the street.

Oscar and Cathy have had the foresight to book a visit in advance to the Museo Cappella Sansevero ('Funerary chapel with renowned sculptures'), and we have just time for a light lunch at the café in the piazza behind the San Domenico Maggiore before they're off to the Cappella just half a block off to the side.

In their absence, we're undertaking some further explorations -- the Via dei Tribunali is the central and most important of the three central east-west roads, all three pedestrianized, and we're here near the end of it, where the pre-16th century city ended. That church a bit farther along is the Chiesa di San Pietro a Majella in the Piazza Miraglia, but we're going the other way, along the Tribunali towards the Duomo.

The medieval belltower is related to the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore alla Pietrasanta on the left.

The belltower is said to date from the 11th century.

Go Team! Football mania.

The nearly always interesting Via dei Tribunali

That's the Basilica di San Paolo Maggiore, but . . .

. . . we haven't time just now to investigate.

The name of that little establishment embedded under the basilica porch is Assaggia La Nostra Pizza: 'Taste Our Pizza'.

That's the Church of San Lorenzo Maggiore and its belltower. We'll come back later.

A bit farther along is the Chiesa dei Girolamini. No time now, because . . .

. . . we're here for the Duomo.

Officially, it's the Cathedral of the Assumption of Mary (Cattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta), but it's also known as the Cattedrale di San Gennaro after St Januarius, the city's patron saint (whose blood turns to liquid from time to time, miraculously).

Hot ziggity, another lion

It was commissioned by King of Naples Charles I of Anjou (r. 1266-1285), in the Angevin Gothic style, and completed under his grandson Robert the Wise in the early 14th century. It was positioned on the foundations of two very early Christian basilicas, traces of which remain. The façade is said to have been renovated in Neo-Gothic style and only completed in 1905, though the central front door is from the 15th century.

The structural design of the interior is an ordinary Latin cross with a nave and two side aisles. The apse boasts an enormous extravagant gilded sculpture of a throne with Mary asscending from it into . . . well, the dome perhaps. The gilding is so enthusiastically done that . . .

. . . it's virtually impossible to see what it's about.

The Chapel of San Gennaro created in the 17th century, with a life-size bronze statue of the patron saint in the centre niche and a reliquary of gold holding his skull on the left foreground, wearing a bishop's vestments and mitre. Completed in 1646, it was designed by the Theatine priest/architect Francesco Grimaldi.

San Gennaro is said to have been serving as Bishop of Benevento when he was tortured and beheaded in nearby Pozzuoli in 305 during the Diocletian persecutions. He was made the patron of Naples in 472 for his protection in the eruption of Mt Vesuvius of that year. His tomb was moved from the Catacombs to the Duomo in the 9th century, and in 1497 other supposed remains were brought from other sites in Italy, including the skull and miracle-blood, eventually into his own chapel here.

It's the main centre of the Tesoro di San Gennaro, an attached outbuilding built 1608-1646, a Royal Chapel with its own dome, that houses most of the relics of the patron saint. The 'treasure' includes lots of various artworks, but most importantly it's got the ancient 'ampoule' containing the blood of the saint, which is displayed three times a year, 'when the blood usually liquefies'. The tradition holds that if it does not liquefy, disaster will befall Naples

In this and other cases of miraculously liquefying holy blood, the secular consensus is that the phenomenon is due to the presence of a suspension of hydrated iron oxide, which can be easily concocted and decreases in viscosity when stirred. That said, 'on March 21, 2015, the blood in the vial appeared to liquify during a visit by Pope Francis. This was taken as a sign of the saint's favour of the pope. The blood did not liquify when Pope Benedict XVI visited in 2007.'

The dome of the Treasury, with frescoes by Domenichino and Giovanni Lanfranco in the 1630s.

Treasures

That's the side chapel tomb of Cardinal Francesco Carbone, who died in 1405. (We're great fans of spiral columns.)

The Capece Minutolo Chapel, in the right corner of the presbytery or chancel, dates from 1301 and was built for the tomb of Archbishop Filippo Minutolo over a 5th century chapel dedicated to St Peter. The sarcophagus of Archbishop of Salerno Orso Minutolo was built on the left wall in the mid-1300s, when the chapel was still focused on St Peter, but in 1402 the Archbishop Enrico Minutolo entrusted the patronage of the chapel to the 'Capece Minutolo' family, where it remains; he himself joined the party with his own funeral monument in 1405. The Cosmatesque floor here is much admired.

Somebody else's side chapel, probably a church chap. This one's walls are covered . .

. . . with frescoes all over.

The kids get a keepsake memento of their time in the crypt.

The small Chapel of San Gennaro, built in the 1490s, is in the heart of the crypt and boasts a lighted urn within the altar containing some of the relics of San Gennaro.

And that, unsurprisingly, is San Gennaro. Or a simulacrum.

Probably one of the nicest crypts around. Entirely floored with Cosmatesque-style mosaic inlays.

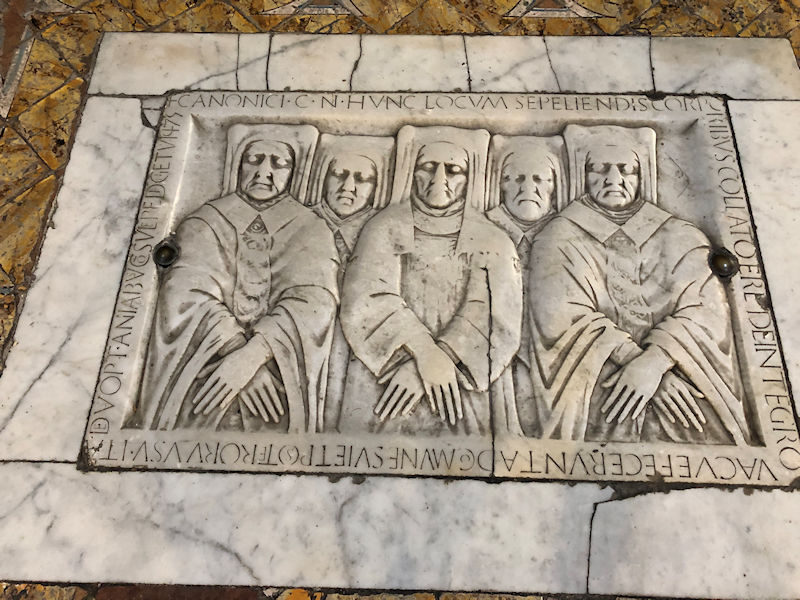

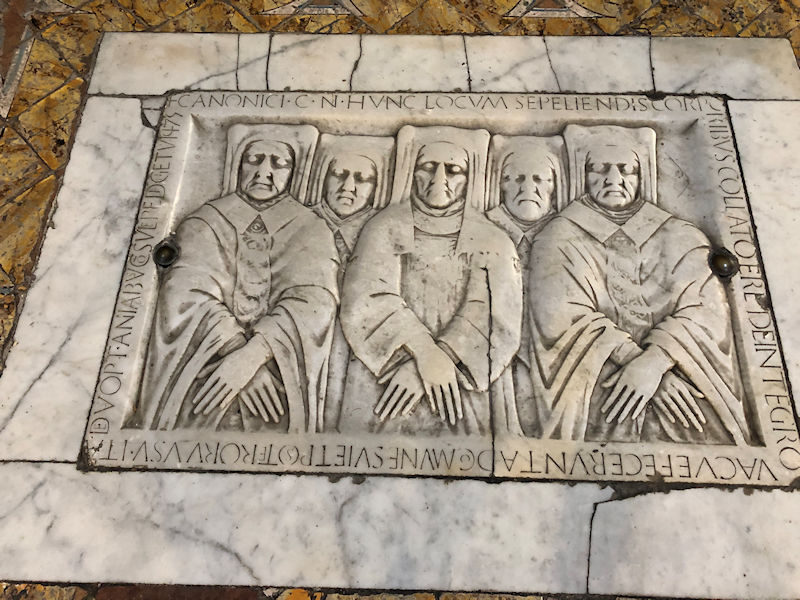

The mid-size nave, looking towards the counter-façade, housing hhe tombs of Angevin rulers including Charles I of Anjou and Carlo Martello

A pulpit with spiral columns

(We're great fans of spiral columns.)

Attached to the Duomo is the 4th century Basilica di Santa Restituta, said to have been founded by the Emperor Constantine -- it was rebuilt and incorporated as an oversize side chapel into the cathedral when that was built in the 13th century. It's got a nave with two aisles divided by 27 very old columns and is a large but separate part of the Duomo. There were various archaeological remains turned up during work under the cathedral between 1969 and 1972, pieces of an Apollo Temple and Roman era houses, that sort of thing.

Family togetherness to the end, apparently, and two traditional faithful dogs instead of one. Sad.

No explanations for this little tableau (but he gets two faithful dogs for his feet as well)

Most interestingly, though, is that back here behind the apse on the right is . . .

. . . this Paleochristian baptistry, the Baptistry of St Giovanni in Fonte, possibly commissioned by Constantine or more likely by the Bishop Severus in the late 4th century, and remodeled by Soter, Bishop of Naples from 465 to 486. It was once in its own building, but is now reached through the chapel behind the apse of St Restituta, as well as through a porch on the far side connecting it to the Archbishops' Palace.

Since the basin isn't deep enough for a full immersion, it's concluded that the clients stood in the centre and the water was poured over their heads three times.

This is considered to be Europe's oldest extant baptistry.

The dome above is decorated with the early Christian Chi Rho and the Alpha-Omega symbols, and . . . .

. . . there are other rather badly damaged frescoes of Christian bible stories up the sides of the dome.

There's an interesting picture on the other side of the altar, on the right . . .

. . . which is a mosaic called the 'St Maria del Principio', made by Lello da Orvieto in 1322.

But it looks like they'd like us to leave now, so . . .

. . . out we get.

Into the protective embrace of the army's Operation Safe Streets

Next up: Pio Monte della Misericordia, Basilica di San Lorenzo Maggiore

Dwight Peck's personal website

Dwight Peck's personal website