|

Dwight

Peck's lengthy tales Dwight

Peck's lengthy tales

Castle-Come-Down faith

and doubt in the time of Queen Elizabeth I

Part

2. THE CONTINENT (1583-1587) CHAPTER

XIV. COLD CITY (1583-1584) "You

will come to learn how bitter as salt and stone

Is the bread of others, how

hard the way that goes

Up and down stairs that never are your own."

-- Dante In

almost perfect gracelessness, the door had recently been painted a luminous green.

The wooden façade, in desperate contrast, had of white long since become dirty

brown. The whole establishment spoke only of neglect and penury and deplorable

taste. Stafford’s house

lay in La Monnaie, just north of the Seine between the Grand Châtelet and the

palace of the Louvre. His predecessor Cobham, in his excitement at going home,

had permitted himself the luxury of a quarrel with his landlord. The new ambassador

had thus arrived at the commodious old "English house" nestled so conveniently

beneath the great mass of the Queen Mother’s half-finished palace, the Tuileries,

just without the city wall, to find the lofty chambers vacant and most of Cobham’s

furnishings departed towards the coast. Only luck, of a qualified sort, and the

help of some of his exiled countrymen, had found Stafford his new house off the

Rue du Bout, an astonishingly ugly little house, long disused, far too small for

his staff and household servants. Lord

Paget stood beside the door of garish green and blew on his fingers. The afternoon

sun sat upon the high roofs behind him. No one responded to his knocking; he and

his companions waited in the disagreeable chill, cloaks drawn tightly about them,

stamping their feet on the bricks to keep them from going numb. "Oh

God, you must have it wrong, Charles," he said to his brother. "No one

lives here. No one could ever live here." The

younger Paget reached across and pounded upon the door. After

another wait, his lordship frowned at his friends and tried the latch, and found

it free. Slowly, he pushed the door open and peeked into the hall. The oak panelling

in the dark room was old and in places split, but it was evident that some program

of renewal had begun, for the furnishings were new and clean and the walls bore

a few hangings that were well chosen. By the stairs that wound tightly above stood

a small table, upon which rested a pile of paper packets near an open diplomatic

pouch. Arundell gestured towards

the dispatches. "The secrets

of Europe." Lord Thomas

chuckled, but glanced uneasily at his brother. Charles Paget, however, removing

his cloak and brushing back his hair with his fingers, seemed not to have noticed. In

the main room, with his back to the long passage, sat Sir Edward Stafford at his

dinner. At the farther end, intent upon her plate, was his wife Lady Douglass.

She sat beneath a tapestry upon the wall that gave a colorful scene of the winged

demons hurrying the howling Lost with pikes and spears downward to the left of

the throne of judgment, a tall seraph looking on complacently. Two unfamiliar

young men dined with the Staffords, one on either side of the table. So far, amid

the sounds of mumbled chewing and clacking cutlery, no one had observed the newcomers’

entry. "Room for three?"

called Arundell. Stafford

leapt to his feet, upsetting his chair. "Charles,

good lord man, is it you?" He began pumping Arundell’s hand with enthusiasm.

"Your lordship," he nodded, stooping to set right his chair, and nodded

again, a little less cordially, to the other Paget. "Here, I am astonished.

Do sit. Tell me what this is." "A

continental holiday, may be," replied Arundell, and made his way to greet

her ladyship, who in seeing him looked less querulous than her custom was. Stafford

followed him round the table, as the other men stood. "Oh you are welcome,

gentlemen!" Abruptly he

remembered himself and turned to bring in the other gentlemen. "Look, you

must know Mr. Constable, who is a very proper young man, the earl of Rutland’s

trusted kinsman, now in his travels. And over here is Mr. Hakluyt, who is our

chaplain. Mr. Arundell, my Lord and Mr. Paget." Arundell

and Lord Thomas greeted the first man and nodded affably to the second across

the board. "Hakluyt is

an Oxford man, you must know more of him. He makes those books of the navigations

in unknown seas. Look you, do sit down. If you have eaten nothing yet . . ." "No,

we have eaten. I fear we disturb. Let us just warm ourselves, if you please, Ned."

Arundell and Lord Thomas sat up to the table as the diners resumed their meal,

while Paget went down to sit before the fire. As

the greetings had progressed, Sir Edward’s brain had not been idle. It occurred

to him that, as pleasant as he found his new surprise, there ought not to have

been surprise at all. Slowly his brow darkened and for a few moments he ate silently.

Arundell, as the servant appeared with cups of warmed wine, watched his host with

some sadness. "Well, you

are right, Ned," he said at last. "Not quite a simple holiday." Stafford

looked up and said, "Mr. Constable is on his road out of Italy and, gentlemen,

we have been debating where are the least civilized, in those parts or in France." "Yes,"

said Constable; "and the question devolves wholly to the point of haberdashery.

Not to put too fine a point on it, sirs, we ask ourselves whether the more barbarous

were to invent these outlandish fashions of attire, as do your Italians, or basely

to imitate them, as do the French." Arundell

laughed. "But then tell me, sirs--I exclude you deliberately, madam--what

barbarian do we accuse for the green door just without?" "Oh

God," Sir Edward groaned. "My door! Oh." "Charles,

we beg your forbearance here in this unfamiliar land," Lady Douglass cried.

"I am too much at fault." "No,

sweet, never say it. My lady, Charles, upon our first arriving, told me that if

I did nothing straightaway for the sad aspect of this house she would destroy

herself. Well then, I ran to Lilly, my man, and I said ‘Beautify this house

at once,’ and he, dull man, ran out and engaged a Frenchman painter who hates

the English mortally, and now we eschew that door and come round to enter through

the garden. Indeed, we pray nightly that a mad St. Bartholomew’s crowd of

the city will come and knock it in." "And

then retire." "Yes,

ha ha, and then retire, their spleens well vented on the loathsome door."

Stafford carefully wiped his fingers on his lap-cloth. "Retiring, you know,

is not the thing which Paris mobs do best." "Ah,

but it is that thing that I do best, my friends," Mr. Constable said; "and

if you will forgive me, I will remove me now to my chamber. I have letters to

write and would not lose this bearer." He rose from the table with a polite

bow towards the lady, then bowed again to the gentlemen. "We shall meet again

soon, I hope, good sirs." "If

I may have my wish, sir," said Arundell amiably. Mr.

Constable took up his rapier and belt from the high back of his chair and, with

another courteous nod, left the room. Mr.

Hakluyt was a thin man of about thirty years, with a nose that frequently drew

comment. Having regained his seat after the other’s departure, he resumed

his meal energetically. Stafford glanced at Arundell. Hakluyt, with a fowl’s

breast in his hands, looked up at Sir Edward and smiled somewhat greasily. Sir

Edward smiled back with a friendly nod. Richard Hakluyt returned to his bird,

and then paused to swallow off some of his wine. His eyes met Lady Douglass’s;

she smiled at him; he tried awkwardly to dip his head in a short bow whilst drinking.

Hastily, he turned down to the other end of the table. Sir Edward, Lord Thomas,

and Mr. Arundell smiled pleasantly back at him. He nibbled furtively at his fowl.

Sir Edward, he noticed from the corner of his eye, was turned away. He raised

his head; Sir Edward swung about and smiled at him. With

elaborate show of finishing, Mr. Hakluyt sat back in his chair and pushed his

plate from him, patting his lips slowly with his lap-cloth and replacing his knife

in its silver holder on the table. He sat for an uncomfortable half minute gazing

bemusedly at the timbers above, as if recalling an entertaining anecdote he’d

been told a day or two before. "Well,

then," he said. "I crave your pardon, madam, for this incivility, but

I must return to the writing of my sermon. It is, you know--a’em--the Lord’s

work." "By all means,

sir," replied her ladyship, smiling graciously. Hakluyt

bowed to the gentlemen, who smiled at him, and then, adjusting his dark jacket,

saying again "sermons always to be written, my good friends" as he backed

away, he left the room somewhat hurriedly, his hard shoes clattering across the

boards. Charles Paget rose

grinning from his place by the fire and took the chair before the half-finished

plate. "Well, my friends,

he is gone," Stafford said after a moment. He frowned quickly. "You

anticipate my thoughts. As custom and use is, I think, I should have been warned

to look for you, should I not, as I am warned of all gentlemen who take the queen’s

passport to travel in these parts?" "I

think you should have," said Lord Thomas. "Defect

of government," said Arundell. "Most reprehensible." "Then,"

Sir Edward replied, more soberly, "then I doubt not this has some taste of

politics in it, eh? What is the cause? Not this Throgmorton business, is it?" "Sir

Edward, you have named the occasion of our coming, but not the cause, which verily

was all upon the note of conscience." Lord Thomas too grew earnest. "The

queen herself and all impartial men do know our loyalty for our bodies to her

majesty, but now our souls must speak to God, and that, Sir Edward, they cannot

easily do in England at this day." "And

one need not ask whether you have been touched in any matter of state?" "Certainly

we have not! But like all honest men in these divisive times we have enemies--who

knows that better than yourself and your good lady?--and we may not go to bed

in good hope, anymore, of arising free men. For you know that this traitorous

Somerville’s taking will be fuel for the brands of those who would burn us

on the flagrant pyres of their bigotry and--." "Tush,

Tom," Arundell said. "Well,

I wax metaphorical. You understand me, Sir Edward. The precisians will rally to

this, mark me, and make their use of it, and we fear a hard hand over all the

papists, while our enemies will grasp upon it to bring us into peril. Hardly should

we ever come out of it in England, thus we have come abroad only until the occasion

of this danger is past." "I

hope you do exaggerate," the ambassador replied. "What, may I expect

a general Exodus? England is England still, where law rules even above the queen." "Does

it so, Ned?" his wife put in heatedly; "or shall we say where the earl

of Leicester and his canting creatures rule above both law and queen!" "Well

put, my lady," Lord Paget said. "Already Mr. Arden, no better man in

the country, nor a truer, is arraigned for treason; and because why? Because he

refuses to take Leicester’s livery upon his back, because he would not let

go his freedom to join that faction; the tale is too notorious. And now Mr. Throgmorton

and my Lord Harry taken up. Who next, Sir Edward?" "Who

indeed?" Sir Edward sat back wearily. "What would your lordship have

of me, then?" "Only

this, sir. We come to you, not only as our friend and (if I may boldly say it)

our kinsman, but as you are her majesty’s lieger here, to beg you write to

her, to assure her majesty that for all things but for exercise of conscience

we will live as dutifully here as any men in the world, and to beg her highness

on our knees to preserve our little livings, and allow us to enjoy them here if

it were possible and readmit us to them at home when passions cool." "I

will say ye said so." "That

is our whole joy." Lord Thomas thought again. "‘Look to a gown

of gold,’ say I, ‘and you will get at least a sleeve of silk.’

And what you may also tell her, we will remain here either with you or else wholly

at your appointment, or if you would not that, then refrain any company here you

would forbid us." "Well.

But you are very silent, Charles," Stafford said, turning about to face Arundell.

"It may be y’are musing upon your recollection of our last meeting.

What was it was said then, do you remember?" "As

I recall, Ned, you advised me hang myself, as the only way to be free of detractors." "Well,

it may be that is what I should have said." Stafford thought for several

moments. "Well, Lord

Thomas, I must say, as I think reason is, that your coming away at this time may

very well give cause to your enemies to suspect your conscience be not clear,

and may breed more mislike than abiding the peril would have done. Notwithstanding,

I will make report to her majesty of your speeches here; but for coming to me,

I must desire ye to forbear me till I know her majesty’s pleasure and receive

her commandment for the course I shall take with you. In the meantime, I would

have you, in friendly counsel, to write to her yourself to say the same." Lord

Paget reached into the bosom of his doublet and withdrew several papers. "Surely

I have done so, if I may avail myself of your bearer." "In

truth, Ned," put in Arundell, "we had thought merely to tuck our missives

silently into your pouch to avoid troubling you with such a small matter." "Tucked

into my pouch? Heh, heh, my dear Charles, I hope my pouch is better looked to

than that." "It is

lying open in the hall." "What!"

The ambassador dashed into the passage, pursued by the others’ laughter.

"Moody! Damn me, where is that bearer? Bring down that bearer." He

returned in a moment, carrying his leather pouch and all his week’s dispatches.

His eye went uncomfortably to the younger Paget, who was toying innocently with

the remains of Hakluyt’s bird. "Here,

your lordship, you may add these to my pouch. But y’must know that they will

come first to the sight of Mr. Secretary." Lord

Paget held up three papers folded and tightly sealed. "They need not come

to Walsingham, Sir Edward. Let me show you, here is one addressed for her majesty,

another for my Lord Treasurer, and a third, if you will permit, for my mother,

lest she worry needlessly." "Very

good. But I am to tell you, the bearer will deliver my pouch direct to Mr. Secretary,

and (I say it in confidence) he will likely have a sight of all of them before

they reach their destinations." Lady

Douglass emitted something like a snort of anger. Lord Thomas caught on only very

slowly. "But they are

sealed, Sir Edward." "Lord

Thomas, boldly I will tell you now, Phelippes, who will receive them for Mr. Secretary,

is competent to open your mouth, copy me out your teeth, and close it again without

your knowing of it. If these cannot be seen by Mr. Secretary, I advise you to

send them by--by another way." He glanced again at the younger Paget, who

still gazed modestly upon the ruins of dinner. "Or much rather, not to send

them at all." Michael

Moody interrupted by entering with young Painter, the courier, firmly in tow.

Stafford held up the open pouch and let the papers fall severally through his

fingers to the table. Painter shone with embarrassment and tried stammeringly

to indicate that, passing up to the study, he had stayed merely to answer the

call of nature. The ambassador cut him off with a gesture. "Moody,

bring him back and have him ready to ride within the hour. Mr. Constable will

have a letter for him, too, see that he has it, and I shall have another." Moody

nodded and gathered up the papers and pouch. Painter followed him silently back

towards the hall. "And

Moody, for God’s sake, set someone near the door!" Stafford

turned to the others when his men had departed. "Ye

see how it is, gentlemen. The fellow’s father once pleases the earl of Leicester

with his moral tales and pleasant narratives, and not only he must have the best

post in the Tower armories, but his noddyheaded boy must carry all my news. There

are but two ways to gain employment in England, i’faith, which is either

to murder a man for Leicester or else dedicate a book to him." "Another

time," said Arundell, "let me tell you how to lose employment there." "Ha,"

Stafford laughed. "Well, for your company here, only I will say that you

know there be papists of two sorts here in Paris, those whom we call papists of

state and those we call papists of religion only. With the former ones I would

by no means have you to meddle, so that I may report you keeping clean apart from

them. And you, Mr. Paget, I say this no less to you, sir. You know you have not

dealt plainly with me." Paget

looked up slyly at the mention of his name. "But, Sir Edward, neither have

you found for me the favor of her majesty I might have looked for." "Paget,

I told you when last you came, you must avoid this Morgan and all his brood, and

you must do for her majesty some of that signal service you never cease to promise." "Mr.

Morgan is as honest an Englishman as any on live," the other said heatedly. "No

he is not. He is a busy meddler, and a Welshman too, and while you league with

him I can report no good of you. No more for you, my friends. I say it in old

friendship. Do hold yourselves free of--. And then this Roman widower, who had

buried twenty wives, in his perfect confidence did marry with the widow of twenty-two

husbands, and all the city of ancient Rome did fall to wagering huge estates who

should bury other, ha ha." Grimston,

another of the ambassador’s household, had come through the door with a message

for his master. Stafford read from the paper and thanked the man, continuing,

"And all the aged men daily gathered before the house to cheer the husband

on, and the grave matrons of the city likewise assembled daily to do their best

for the wife, you see." He

looked over to where Grimston had departed. His companions chuckled amusedly at

the anecdote until the footsteps were no more to be heard. "Grimston

is the Secretary’s man," Stafford explained simply. "Well, enough.

Where may I find you?" Arundell

sat forward. "For the moment I am with a man named Fitzherbert in the Ruelle

du Foi on the other side the river." "I

know the man, a good man. I’ll inform her majesty what you say. I may have

word for you within this fortnight. And I must beg your pardon, gentlemen. Painter

must be prompt upon his journey." Arundell

arose and shook his hand. "Pray

God, Charles," Sir Edward said, "you may have your wish. If it is this

Throgmorton business I hold little hope for a speedy reconciliation." "We

shall see." Arundell bowed to Lady Douglass, who sat scowling in a sort of

slow anger. Lord Thomas took up his cloak and bowed likewise, and the three of

them departed from the notorious door. They

had not brought horses over, so to avoid another long walk round by the bridges

in the cold they decided to try the river traffic. At the foot of the Rue de la

Monnaie, across the wide bank, there were several small wharves and a few unoccupied

boats tied up to them. They looked a hundred meters across the stream at the tiny

mounds of islands below the Ile de la Cité, where some men were to be seen working.

Up river, obscuring all but the rooftops of the Pont au Change, lay the Millers’

Bridge, with ten or eleven wheels reaching across from the shadow of the Palace

of Justice on the island. They set off walking downstream past the school of St.

Germain in hopes of flushing out someone to row them over. The bitter wind blew

down behind them from the north and forced them to lean sideways into it with

necks drawn in. "‘The

wrathful winter, ‘proaching on apace,’" Arundell quoted, "‘With

blust’ring blasts had all ybared the treen--’" The

others looked at him in mock rancor. The

cold, gray water swept by below them with a hushed rustling sound, swirling against

the rocks and pilings and carrying bits of refuse and wood in its flow. Alongside

them the graceful Hôtel de Bourbon rose amid the ruin of the ancient city wall,

and a little further on, the mighty Louvre, the high lines and bellied towers

and embattled parapets of the medieval fortress softened by its long new windows

and gardened walks, loomed enormously against the sky. "Damn

me," cried Lord Thomas, who had seemed lost in thought. "I should like

to know whether widower or widow won the hazard." "Ah

ha, the husband won, Tom," Arundell said. "His friends, at the unhappy

woman’s funeral, crowned the worthy man with a laurel wreath and, setting

him atop the wagon, danced victoriously before it as she rode to burial." "What,

Charles, is it true?" "Whether

true I cannot say. The tale is in old Painter’s book, The Palace of Pleasure,

that Sir Edward spoke of, do you look to it yourself." Having

found a boatman, they clambered aboard his punt and dropped down the cold river

towards the center, then huddled together against the wind as the man rowed powerfully

back against the current. Alighting by the city wall, they entered through the

Porte de Buci and separated, Arundell turning in to Thomas Fitzherbert’s

rooms near the Hôtel St. Denis. Fitzherbert kept these chambers chiefly as a stopping

place for himself and his acquaintances, and so, though altogether much lived

in, they little looked it, remaining bare and cheerless when unoccupied, pleasant

only when pleasant people stayed in them. Tom Throgmorton resided there often;

William Tresham was there now, newly evicted from his old place for a failure

to pay up his keep. Fitzherbert himself used them but seldom, for in his post

as the English secretary of the Queen Mother, Catherine de Medici, he was usually

fain to follow the court, and otherwise he often moved to Rouen, where also he

had business. Arriving in Paris

some few days earlier, Arundell and Lord Paget, ignorant of the city, had gone

first to the College of Clermont near the Sorbonne. The Jesuits there, in particular

Father Claude, the duke of Guise’s favorer, had directed them to Charles

Paget’s rooms in the Rue de la Harpe, the left bank’s principal boulevard.

Lord Paget promptly moved in with his welcoming brother, while Charles found hospitality

with Fitzherbert not far off. There

are not many things so disheartening as a strange city in a foreign nation, in

the gathering dusk of a winter evening, especially when one is not only cold but

nearly penniless and not very far from friendless. The loneliness of the twilight

hour weighs upon one’s heart. The people rushing by one have homes to go

to, warm homes, probably well lit. Into

what a morass had he fallen unawares? No money with which to buy a position in

some court or entourage or a command in someone’s army; no skill to offer,

no military expertise save a few skirmishes in his youth. He had all his adult

life been a courtier, and a courtier might or might not capably acquit himself

in the offices granted him, but one skill indispensably he must have, that of

getting and retaining favor. Arundell had lost all favor. A courtier without a

court can scarcely be said even to exist. Eight

days after his visit to Stafford’s house--it would now have been Thursday,

the 10th of December 1583 in the English style; in Catholic countries, since the

advent of the pope’s new calendar, it would be reckoned the 20th--Arundell

lay late in bed watching the gray sky above the towers of the Hôtel de Nesle toward

the river, and listened to Tom Throgmorton clattering pots near the low fire trying

to stir up something for a breakfast. Similarly in former years, he had lain abed

gazing at Baynard’s Castle on the wintry Thames, while Kate had stirred up

a new fire and then crept back beneath the quilts beside him. Throgmorton, an

honest fellow, was a jolly poor substitute for Kate. But Charles found it entertaining

to try picturing Kate as she would have looked, bending at the grate where Throgmorton

bent now, tossing her hair back irritably, laughing perhaps in mock cruelty as

she came back to him with icy fingers on his chest. From

his bed, Charles heard heavy boots tramping up the stair. Tresham, who was reading

in the front room, went to the door; the sounds of greeting came down the open

passage. He watched young Throgmorton reach into the high chiffonnier and extract

a shirt with which to cover his thin, hairless chest. Lord

Paget came in first and called, "Where’s to eat?" He darted straight

for the fire basin, where he commenced at once, heedless of expense, to throw

new coals under the grate. "Hey,"

called Throgmorton, and playfully elbowed him away. "Tonight’s coals;

mind your freedom with us, sir!" Charles

Paget came in after his brother, followed by Tresham still in morning undress,

and after them came two others. One was a man somewhat older than the rest (who

were all, save Throgmorton, in their early forties), and somewhat stouter as well;

the other was a tall man gone prematurely gray, wearing the remains of fine attire,

now in disrepair. Greetings

were echoed round the room, and Lord Paget undertook to introduce Arundell to

the tall man, Charles Neville, the earl of Westmoreland, no older, indeed a little

younger than Arundell, yet a veteran of thirteen years’ exile. He had been

attainted as a traitor for his leadership (to flatter him) of the Rebellion of

the Northern Earls in 1569, and had wandered across the continent ever since,

enjoying a small Spanish pension in consideration of his rank and trying generally

to make himself useful. "We

meet at last," his lordship said in what was meant to be a cordial tone,

but came off sounding fatuous. "You know, Mr. Arundell, we must be something

like, let me meditate a space, something like second cousins, are we not?" "By

marriage, your lordship," Charles replied, taking the earl’s proffered

hand a little diffidently, forced to rise higher from the bedclothes than modesty

required. "Well, my brother

Howard has lost his wonted agility, has he not? Not nimble enough at the last,

eh? But you’ve come out of it right enough; well played!" "Thank

you." The older gentleman

was Dr. William Parry, a man whom many of the stricter sort were inclined to avoid

for the scrapes into which he’d none too honorably fallen in the past, but

nevertheless a man who found himself (one presumes for his love for the queen

of Scots) made welcome in the Morgan circle. Only recently having obtained his

degree in the faculty of law, he wore his learning well, and spoke intelligently

and soberly, and expressed authentic-seeming pleasure at meeting Arundell, whom

heretofore he had seen only from afar when in former years he had hung on the

fringes of the English court. Amenities

completed, the gentlemen ranged about the room finding places to settle; they

were awaiting the arrival of Morgan himself, whom business had detained. A shout

came from the outer room, and Thomas Morgan stood in the narrow doorway. Still

dressed in his great cloak and spurs, the Welshman looked the more imposing for

this evidence of haste, as if he were a man whose time is too valuable to be spent

in dressing and undressing for every occasion, a man always caught in flight,

as it were, from some prince’s chamber to another’s council of state,

with scarcely time between for bothering about his cloak. From his shocking red

hair to his broad, blocky shoulders to his travel-stained hose, Morgan was a picture

of the energetic, industrious man of affairs. From his beginnings as a mere secretary,

he had come a long distance. In his few years in Paris, indeed, he had contrived

to wrestle from old Glasgow’s grasp the management of all the queen of Scots’s

affairs; in this capacity, he corresponded with princes indeed and, controlling

as he did the captive lady’s purse-strings, her French dowry and her annuity

from the king of Spain, he was much sought after by nearly all the English Catholics

on this side the sea. If sometimes it was whispered that events had yet to prove

his qualifications for these tasks, yet Morgan betrayed no want of confidence

in himself and had lately taken to beginning his letters to great prelates and

high ministers of state with not much more than "Sir." As

Morgan greeted him, Charles took occasion to watch the man’s behavior. He

grasped Arundell’s hand firmly enough, and even ventured a conventional jest

upon his dishabille, but he glanced busily about the room the whole while, as

if checking off an invisible attendance card, and never met Charles’s eyes.

Morgan welcomed the new expatriates

and informed them that already he had written to their saint and very good lady

the queen of Scots, begging some small maintenance for her ancient servants Lord

Paget and Arundell, now in want for her sake. He doubted not (for her trust in

his judgment) that a favorable reply might be expected. He had been yesterday

with Tassis, the Spanish agent, about the long-awaited creation of an English

regiment in the prince of Parma’s army, and he foresaw better-filled pockets

for all of them who cared to enlist, especially for Westmoreland, whose command

it was to be. Dr. Parry, he continued, so recently come to them in autumn, was

soon to leave again, bound shortly for England where he had in hand some special

service for the cause, the secret of which did not yet bear divulging. Finally

Morgan came to his last news, which bore on the new arrivals’ case. "Not

a few days after you twa be departed of the ambassador’s," he said,

"did a’ not receive a special rider with missive from the Secretary,

reading what, think ye? Wall, it warned him particularly of y’r dangerous

flight and bid him in her majesty’s name t’carry a verra watchful eye

over y’both, to understand what ye may practice or deal in to the prejudice

of the realm; and said furthermore that the queen ware assured that Sir Edward’s

lady’s near kinship wi’ y’both should ne’er make him remiss

to perform his duty." Arundell

started slightly. "That’s

a bit queer, is it not?" "Indeed

it is, verra quare," Morgan replied, "and shows what good faith Sir

Edward may expect from Walsingham and all that brood. And look ye, a’ grew

in a rage thereat, and wrote a letter full o’venom to his old pallie the

Lord Treasurer, to tell him of these foul aspersions and demand apology; but a’

ne’er shall have it, for Mr. Secretary will look old William calmly in th’eye

and say he wrote but what her majesty bid him write." Arundell

felt some distress for his friend Stafford; for the others, the business seemed

but a lively joke. "But

how is this known all so particularly?" he asked. "One

of that house is ours." Morgan was manifestly impatient of delay. He glanced

round the room as if to inquire what business was left untouched upon; then he

spun to face Arundell again and said briskly that he never doubted Charles would

soon have his health again and need no longer languish his days away abed. With

that, and with a series of abbreviated nods like cervical twitches round the room,

he departed. Westmoreland, waving apologetically at his newly-met kinsman, hastened

to overtake him, and the brothers Paget and Dr. Parry followed after. The image

came in Arundell’s mind of a duck, with an absurdly red head, bustling across

a barnyard with her file of ducklings, in ruffs and hangers, trailing behind her.

For

Charles Arundell, matters were in abeyance. More than anything else there was

only waiting, and for him the sensation of dangling. He sent once to Stafford,

and had word in return that he must wait a little longer. Morgan had written once,

a week into January, to inform him that the queen of Scots had been advised of

his worth and need, and that one had now only to wait. To

wait then. Only tarry a little; go soft a while. Linger here in bare rooms. Stay!

stay; abide this little time. Only wait; December grows to January, as the Yule

season passes (in these bare rooms), while others act, do, bustle everywhere on

errands. Arundell hung on nervously, cleaving to his little hope, dreaming of

errands to bustle on. Occasionally he attended mass in the chapel in the next

street, and now and then he walked out and paid brief visits to the famous parts

of the city, strolling of a gray morning past the Petit Châtelet and across the

Petit Pont, to survey the grand heights of the cathedral of Notre Dame; thence,

perhaps, he would descend the length of the island, across the boulevard and beneath

the arches into the great courtyard of the church of Sainte Chapelle. Another

time he would walk through the serried colleges of the university district, passing

the scholars in their gowns and the monks in theirs, or scurry through the stews,

brushing away the gay women who leered up at him and the lurching drunks who sought

clumsily to slit his purse. All the time he was waiting, tarrying, dangling. For

some time, he had little news. Throgmorton was out of the city, and Tresham had

ridden to the prince of Parma’s camp at Tournai, concerned that the formation

of the new regiment should go through without impediment. Fitzherbert brought

word of more arrests in England. Northumberland had been transported to the Tower

of London, but had not yet been charged substantially. Good Mr. Arden had been

executed, though his mad son-in-law Somerville had escaped a public hanging by

conducting a private one in his Newgate cell. The earl of Arundel had been arrested,

as had Mr. Shelley, along with a host of their servants and a number of Sussex

men thought to have known something either of the Petworth meeting or of Lord

Paget’s flight. Not long

afterward, Arundell was sitting at midday before a low fire, reading laboriously

a book of tragical histories in French. He answered a quiet knock and found the

man he’d once met at Petworth, then called Señor Martelli, who now wore clerical

garb and reintroduced himself as Father Henri, and summoned Charles abroad. Together

they walked southward a short way, then westward almost to the city wall at the

Porte St. Germain, whence they turned eastward again along the Rue des Cordeliers

to the church of that name. They entered the dark, silent edifice by the main

portals, and then Father Henri left him alone. The

church was bitterly cold and seemed entirely vacant but for himself, left to the

huge motionless shadows cast by columns and arches in the pale light that shone

down from dusty clerestory windows at the top of the vault. He stepped across

the stone floor, startled by the echoing clatter of his own boots, and ventured

further down the center of the nave. Still no one appeared to greet him. As

slowly he approached the raised chancel, he discovered that the effect of the

place had begun to grow in him. Blocks of chilled stone rose silently all about

him in arching shapes. He stood in a small pool of rose light at the foot of the

steps and gazed past the altar into the apse, where dirty ornamented windows threw

a halo of pallid sunlight round the great tortured crucifix mounted there. Beneath

his feet he felt the worn contours of the effigies of buried knights and churchmen,

their names with their poor faces trodden away by the passing generations. The

marble heads of noblemen stared sternly or forlornly from the walls, guarding

in the darkness the skulls of their subjects plastered within their niches. The

stillness of the place began to seem less annoying (because he had been called

out and left to stand idly) than almost comforting, as if he had wandered into

a sort of haven. Here, it seemed for the moment, the passionate men and actions

and causes and the mighty struggles of the daylit world might carry on around

him throughout the busy city and leave him unnoticed and undisturbed. Here suddenly

his concerns over factions and loyalties, even simple livelihood, seemed less

real, or at least less immediate, and he sensed a certain tentative peace in a

world that was above faction and above violence, above even common notions of

loyalty. Perhaps it was some spiritual breath that filled the air of the place

that made him feel so, or merely the presence of dark, cold death on every side. Behind

him the great doors swung heavily open. The deep, echoing clatter returned him

abruptly from his reverie, and instinctively he stepped across into the southern

aisle, where the columns and the gloom hid him completely. Murmuring voices and

the tread of boots approached him down the nave, and he recognized Lord Paget

and Twinyho, his man. "Halloo!"

Paget called in a voice that boomed through the vaults and came back to startle

him more loudly than he’d sent it out. He and Twinyho stood somewhat abashed

before it. "Hello,"

Arundell replied from just beside them. Both leapt half a meter into the air. Lord

Thomas greeted Charles warmly. They had seen little of one another in the six

weeks of their sojourn in the city. He professed a similar ignorance of the cause

of their summoning out, but seemed less disposed than Arundell had been to wait

patiently for a sign. Presently,

however, the sign came. There was a rustle of silk from the direction of the choir

in the chancel, and out of the shadows a priest stepped forward. Hitherto unnoticed,

the man had been seated in the darkness, watching Arundell, probably, for some

reason of his own, since he had entered the church. The man motioned them to follow

with his black-robed arm and led the way out of the southern door into the cloisters

beyond. In the dim sunlight, he could be seen; without the gentleman’s jacket

and hose, in the long soutane and blocked cap of the Jesuit, he was Robert Parsons. Parsons

led them silently along a corridor open in stone arches on the left and hard against

the building’s wall on the right, passing from time to time through dark

tunnels where small overhanging outbuildings closed them in entirely. On the farther

side of the deserted quadrangle ran a similar walk, enclosing a half-paved court

open to the sky, with gray cobbled walks radiating from a great stone well in

the center. Only gradually did Arundell become aware of obscure figures moving

across the yard as well. As the little party passed into a complex of masonry

at the corner of the square, the other men across the way were lost from view. Suddenly,

before the tombs of several abbots set into the wall, the parties met. In the

shadows of the corridor, three men approached and stopped. Father Parsons took

Lord Paget’s arm and led them all into the somewhat better light of an archway,

and there made introductions. The first man was a dark Welshman of middle size,

dressed in the robes of a secular priest, who was called Father William Watts

of Rouen. The second Charles had met not long before at Petworth, then Captain

Pullen, the earl of Northumberland’s retainer and once his deputy at the

Castle of Tynemouth, now likewise dressed in priestly attire, and transformed

by it, looking less the bluff, laconic soldier Charles had taken him for and more

the austere servant of the Lord. The

third man, taller than either, stood behind them. He stood slightly bowed by some

fifty years or more, but his thin frame still rose above Parsons by a full eight

inches. His long, thin, delicately bearded face, with its large eyes, clear and

steady, framed by a three-cornered cap, a hood thrown back, and below it, a stiff

robe unadorned but for a row of tiny buttons down the front, spoke immediately

of enormous intelligence and commensurate self-respect. The man merely gazed,

as if appraisingly, at Arundell and Lord Paget. "This,

gentlemen, is Dr. Allen." Parsons paused to let the effect sink in, which

promptly it did. William Allen,

in exile for over twenty years, once a colleague of the great doctors of Louvain,

more recently the founder of the English seminary of Douai then of Rheims, was

the unofficial head of all the English Catholics. The idea of meeting so important

a personage, of consuming his time even by an introduction, made Arundell flush

with embarrassment. "He has come," the Jesuit continued in his broad

Somersetshire English; "he has come from Rheims especially to welcome you

to these parts."

|

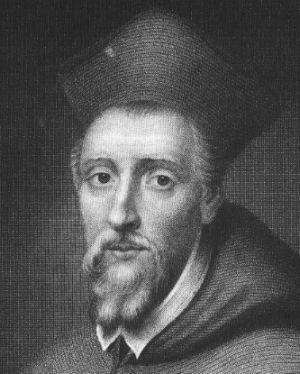

William,

Cardinal Allen (1532-1594); engraved J. Cochran. | Lord

Thomas and Arundell stood at a loss to know whether they should shake the man’s

hand, or kiss it, stand or kneel, or simply flee back down the corridor. But Allen

contrived to put them more at ease with a half-smile and a simple gesture of the

hand. Then Parsons came to

the business, entering into somewhat convoluted expressions of sympathy for their

present circumstances. These required a lengthy exposition of the deeper historical

meanings of the heretics’ persecution of the faithful, of which the difficulties

of these men here and of their compatriots now in English prisons were only a

small, albeit to them a painful part, but not unlike the trials of the ancient

faithful under the pagan Romans. Arundell understood the Jesuit’s analysis,

in which the new men with their self-serving new creeds were shown to be intent

upon erasing the old faith from the English realm, in order to clear their own

paths to personal gain; he was not so certain that it was all so simply a matter

of the Devil at work in the human theater. But he listened politely without demur,

content to allow Parsons the rather streamlined interpretation doubtless necessary

for his passionate continuance in the cause. All

this declined into a martyrs’ roll of priests hanged and simple gentlemen

turned out of their homes and forced to lie in common prisons, like poor Verstegan,

lately incarcerated in the Bishop’s Prison in Paris at the instance of the

English ambassador in this town, but Parsons came round finally to Lord Paget

and Arundell. He knew of their kinship with Sir Edward Stafford, and he hoped

he might advise them in friendliness and mere love not to presume upon that thin

bond for fair treatment from the government. They would never be reconciled to

the English state, he said, no matter what fond hopes they may have harbored,

and they must never allow themselves to be suborned by Stafford’s words into

any act of bad faith with their coreligionists here. But

this was only half the Jesuit’s theme. He embarked now upon a too circumstantial

explanation of the factional strife in the English College in Rome back in 1579,

which had from that time and place grown and spread like a chancrous disease and

now threatened the unity of the body of the English Catholics here on the continent

and even at home, all of which disaffection and acrimony gave scandal to their

enemies and undermined their hopes for aid from their friends. The causers and

setters on of this division and broils, he said, were notorious for a sort of

busy malcontents, envious ne’er-do-wells who thought more of wealth and worldly

power than of any true service to God. Many of them were thought to be secretly

in the employ of the English government, especially to divide the poor Catholics

here and set them one against another, and to that purpose they played upon the

weaknesses and infirmities of frightened men to turn them against their natural

superiors. Amongst those whom he named as members of this factious crew were the

bishop of Ross, Mr. Tresham and the earl of Westmoreland, the Lord Claude Hamilton

of Scotland, Dr. Parry who was an open spy, the disreputable priests Gilbert Gifford

in Rheims and Edward Gratley in Paris, but the chief and head of all, he said,

was a certain dissolute Welsh madman by the name of Morgan. May the Lord deal

with justice not with mercy in his case. "But,

your reverence," Lord Thomas cried, "this Morgan is my brother’s

greatest companion!" Parsons

held his eyes for a long moment. "That, your lordship, is why I have ridden

specially from Rouen to warn your lordship from this infection, ere it be too

late to withdraw yourself from other men’s suspicions." Lord

Thomas shifted uneasily from one frozen foot to the other. Then Dr. Allen stepped

solemnly forward. "Hear

me, friends," he said. His face was settled in a sort of wise energy. "The

cause of God has never had more need of good men. It has never, perhaps, been

more endangered by the malice of bad men. We look to you to join with the good,

and to avoid the bad. In our lifetimes, with your help, we shall

worship freely in England again." Looking

at the man’s eyes as he spoke, for that moment Arundell had no doubt that

he was right. Parsons went

on to say that he was soon to write personally in their behalf, using Dr. Allen’s

good name and credit, to the pope in Rome and the king of Spain, and that he would

soon have welcome news for them in the form of some small living. He expressed

confidence that they would not, before that relief should come, be driven by want

to any desperate acts. Then Pullen led them away towards an exterior gate letting

from the cloister of the Cordeliers into the street just near the city wall. Arundell

glanced back and saw Allen and Parsons standing together looking after them. In

the street, Lord Thomas seemed awkward in Arundell’s presence, and after

a promise to meet soon, he hurried away with Twinyho at his heels. Arundell

walked slowly back towards his chambers. The Jesuit’s speeches concerning

Stafford were only what he had expected, raising again a genuine problem--in short,

was Sir Edward to be regarded as his friend or enemy?--but adding nothing toward

its resolution. Parsons’s insistence about Morgan’s crew, though, this

being pressed to choose sides in a game he had not yet learned how to play, this

unsettled him. It confirmed rumors he had lately met of animosities and smoldering

fires within the papist community, but left him without a clue about what the

issues were and what was at hazard. Charles thought carefully over all he knew

of the men he’d met on each of the two sides, if "sides" were really

the correct word, and if indeed there were only two--the Jesuit and his colleagues

with their moral straightness and their singlemindedness and their religious devotion

the intensity of which he found (he confessed it to himself) alarming; and on

the other side, Morgan, whom he had distrusted from first meeting, and Charles

Paget, whom he had never liked, and their less godliness but equal singlemindedness.

And were there other factions yet unheard from? With so many zealots all under

such formidable strain, how could there not be, now or someday, as many factions

as permutations of a single creed, as many as opportunities for jealousy and disagreement? There

was no solution now to be had. He was as much in the dark, as lost among uncertain

friends and veiled enemies, as he had been in Leicester’s home court in the

palaces of the queen. But here, at least, both sides, all sides, seemed prepared

for the time to bid for his allegiance with the promise of pensions. There

was nothing for it now but to go on waiting, but waiting for what, really, Arundell

could not have said.

| Go

back to the Preface and Table of Contents |  | Go

ahead to Chapter XV. "My Lute, Awake!" (1584) |

Please

do not reproduce this text in any form for commercial purposes. Historical references

for events recreated in this story can be found in D. C. Peck, Leicester's

Commonwealth: The Copy of a Letter Written by a Master of Art of Cambridge (1584)

and Related Documents (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1985). Feedback and

suggestions are welcome, Please

do not reproduce this text in any form for commercial purposes. Historical references

for events recreated in this story can be found in D. C. Peck, Leicester's

Commonwealth: The Copy of a Letter Written by a Master of Art of Cambridge (1584)

and Related Documents (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1985). Feedback and

suggestions are welcome,  .

Written 1973-1989, posted on this site 10 June 2001. .

Written 1973-1989, posted on this site 10 June 2001.

|